Difference between revisions of "Orange Book"

From Rx-wiki

m (→History) |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | To contain drug costs, virtually every state has adopted laws and/or regulations that encourage the substitution of drug products. These state laws generally require either that substitution be limited to drugs on a specific list (the positive formulary approach) or that it be permitted for all drugs except those prohibited by a particular list (the negative formulary approach). Because of the number of requests in the late 1970s for assistance from the [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) in preparing guidelines for both positive and negative formularies, it became apparent that FDA could not serve the needs of each state on an individual basis. The FDA also recognized that providing a single list based on common criteria would be preferable to evaluating drug products on the basis of differing definitions and criteria in various state laws. As a result, on May 31, 1978, the Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration sent a letter to officials of each state stating FDA's intent to provide a list of all prescription drug products that are approved by FDA for safety and effectiveness, along with therapeutic equivalence determinations for | + | To contain drug costs, virtually every state has adopted laws and/or regulations that encourage the substitution of drug products. These state laws generally require either that substitution be limited to drugs on a specific list (the positive formulary approach) or that it be permitted for all drugs except those prohibited by a particular list (the negative formulary approach). Because of the number of requests in the late 1970s for assistance from the [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) in preparing guidelines for both positive and negative formularies, it became apparent that FDA could not serve the needs of each state on an individual basis. The FDA also recognized that providing a single list based on common criteria would be preferable to evaluating drug products on the basis of differing definitions and criteria in various state laws. As a result, on May 31, 1978, the Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration sent a letter to officials of each state stating FDA's intent to provide a list of all prescription drug products that are approved by FDA for safety and effectiveness, along with therapeutic equivalence determinations for multi-source prescription products. |

The list was distributed as a proposal in January 1979, and the finalization of the first edition was distributed in October of 1980. The book was provided with monthly supplements and annually a new edition would be published. Each subsequent edition included the new approvals and made appropriate changes in data. | The list was distributed as a proposal in January 1979, and the finalization of the first edition was distributed in October of 1980. The book was provided with monthly supplements and annually a new edition would be published. Each subsequent edition included the new approvals and made appropriate changes in data. | ||

| − | On September 24, 1984, President Reagan signed into law the [[Drug Price Competition and Patent-Term Restoration Act]] (Hatch-Waxman Act). These 1984 Amendments to the Food | + | On September 24, 1984, President Reagan signed into law the [[Drug Price Competition and Patent-Term Restoration Act]] (Hatch-Waxman Act). These 1984 Amendments to the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act require that FDA, among other things, make publicly available a list of approved drug products with monthly supplements. The Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations publication and its monthly Cumulative Supplements satisfy this requirement. |

The Hatch-Waxman Act's informal name comes from the Act's two sponsors, representative Henry Waxman (D) of California and senator Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah. It sets forth the process by which would-be marketers of generic drugs can file Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to seek FDA approval of the generic. Generic drug applications are termed "abbreviated" because they are generally not required to include pre-clinical (animal) and clinical (human) data to establish safety and effectiveness. Instead, generic applicants must scientifically demonstrate that their product is bioequivalent (i.e., performs in the same manner as the innovator drug). | The Hatch-Waxman Act's informal name comes from the Act's two sponsors, representative Henry Waxman (D) of California and senator Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah. It sets forth the process by which would-be marketers of generic drugs can file Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to seek FDA approval of the generic. Generic drug applications are termed "abbreviated" because they are generally not required to include pre-clinical (animal) and clinical (human) data to establish safety and effectiveness. Instead, generic applicants must scientifically demonstrate that their product is bioequivalent (i.e., performs in the same manner as the innovator drug). | ||

Revision as of 17:09, 1 November 2014

The Orange Book, formally titled Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, is a comprehensive list of approved drug products published by the FDA. It is widely accepted as the authoritative source for determining therapeutic equivalence among multisource drug products. Available on-line as the Electronic Orange Book (EOB), it aims to provide public information and advice to health professionals and agencies about drug product selection and to foster cost containment. Therapeutic equivalence (TE) ratings are independent of approval status.

Contents

History

To contain drug costs, virtually every state has adopted laws and/or regulations that encourage the substitution of drug products. These state laws generally require either that substitution be limited to drugs on a specific list (the positive formulary approach) or that it be permitted for all drugs except those prohibited by a particular list (the negative formulary approach). Because of the number of requests in the late 1970s for assistance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in preparing guidelines for both positive and negative formularies, it became apparent that FDA could not serve the needs of each state on an individual basis. The FDA also recognized that providing a single list based on common criteria would be preferable to evaluating drug products on the basis of differing definitions and criteria in various state laws. As a result, on May 31, 1978, the Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration sent a letter to officials of each state stating FDA's intent to provide a list of all prescription drug products that are approved by FDA for safety and effectiveness, along with therapeutic equivalence determinations for multi-source prescription products.

The list was distributed as a proposal in January 1979, and the finalization of the first edition was distributed in October of 1980. The book was provided with monthly supplements and annually a new edition would be published. Each subsequent edition included the new approvals and made appropriate changes in data.

On September 24, 1984, President Reagan signed into law the Drug Price Competition and Patent-Term Restoration Act (Hatch-Waxman Act). These 1984 Amendments to the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act require that FDA, among other things, make publicly available a list of approved drug products with monthly supplements. The Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations publication and its monthly Cumulative Supplements satisfy this requirement.

The Hatch-Waxman Act's informal name comes from the Act's two sponsors, representative Henry Waxman (D) of California and senator Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah. It sets forth the process by which would-be marketers of generic drugs can file Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to seek FDA approval of the generic. Generic drug applications are termed "abbreviated" because they are generally not required to include pre-clinical (animal) and clinical (human) data to establish safety and effectiveness. Instead, generic applicants must scientifically demonstrate that their product is bioequivalent (i.e., performs in the same manner as the innovator drug).

How Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations became known as the Orange Book

When Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations was first published in October 1980 it had an orange cover which was continued up until the 25th Edition when the FDA quit selling a printed edition in 2005. For those that prefer a printed version, you can still download the annual edition as a PDF, and print all 1298 pages of the current version (32nd Ed.) and then manually add the monthly updates, which are also freely available.Transitioning to the Electronic Orange Book

Terminology

When using the Orange Book, it is useful to be aware of the terminology it uses and how the FDA intends these words to be defined.

- Bioavailability A measure of the rate and extent (amount) of active ingredient which reaches the general circulatory system.

- Bioequivalents Pharmaceutical equivalents which, when administered under similar conditions, will produce comparable bioavailabilities.

- Generic Substitution The act of dispensing a different branded or unbranded drug product for the drug prescribed. “Generic substitution,” “brand interchange,” and “drug product selection” are but a few of the more common names used to mean the same thing.

- Pharmaceutical Alternatives Drug products are considered pharmaceutical alternatives if they contain the same therapeutic moiety, but are different salts, esters, or complexes of that moiety, or are different dosage forms or strengths (e.g., tetracycline hydrochloride, 250 mg capsules vs. tetracycline phosphate complex, 250 mg capsules; quinidine sulfate, 200 mg tablets vs. quinidine sulfate, 200 mg capsules). Data are generally not available for FDA to make the determination of tablet to capsule bioequivalence. Different dosage forms and strengths within a product line by a single manufacturer are thus pharmaceutical alternatives, as are extended-release products when compared with immediate-release or standard-release formulations of the same active ingredient.

- Pharmaceutical Equivalents Drug products are considered pharmaceutical equivalents if they contain the same active ingredient(s), are of the same dosage form, route of administration and are identical in strength or concentration (e.g., chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride, 5 mg capsules). Pharmaceutically equivalent drug products are formulated to contain the same amount of active ingredient in the same dosage form and to meet the same or compendial or other applicable standards (i.e., strength, quality, purity, and identity), but they may differ in characteristics such as shape, scoring configuration, release mechanisms, packaging, excipients (including colors, flavors, preservatives), expiration time, and, within certain limits, labeling.

- Pharmaceutical Substitution The act of dispensing a pharmaceutical alternative for the drug product prescribed (e.g., different salt [codeine phosphate for codeine sulfate], different ester [testosterone propionate for testosterone enanthate], different dosage form [ampicillin suspension for ampicillin capsules]).

- Reference Listed Drug (RLD) This is the original brand (or innovator) drug that the generic drug is based off of, in which the Orange Book will make its comparisons to.

- Therapeutic Alternates Drug products containing different therapeutic moieties which are of the same pharmacologic and/or therapeutic class that can be expected to have similar therapeutic effects when administered to patients in therapeutically equivalent doses.

- Therapeutic Equivalents Drug products are considered to be therapeutic equivalents only if they are pharmaceutical equivalents and if they can be expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile when administered to patients under the conditions specified in the labeling.

- Therapeutic Substitution The act of dispensing a therapeutic alternate for the drug product prescribed. Examples are:

- chlorothiazide for hydrochlorothiazide

- cephradine for cephalexin

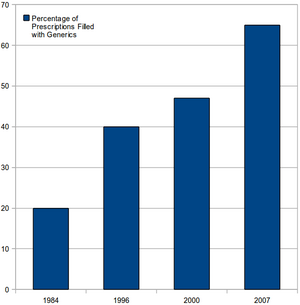

Increasing generic drug utilization

The generic approval process

According to the Orange Book, the FDA will consider a generic product equivalent to a brand drug when both the rate and extent of absorption are not significantly different when administered in the same dose of therapeutic ingredient under similar experimental conditions in studies. The FDA has established specific statistical standards to make a determination of bioequivalence. Two basic criteria must be met for two products to be considered bioequivalent:

- The 90% confidence interval (CI) for the ratio of the mean response of the brand to the generic product, using log-transformed data, is within the limits if they differ by -20%/+25% or less.

- The 90% confidence interval (CI) for the ratio of the mean response of the generic product to the brand, using log-transformed data, is within the limits if they differ by -20%/+25% or less.

This means that the brand and generic must maintain similar blood levels over time. Sometimes the above statistics are misunderstood to think that brand and generic drugs can vary by 20% in strength, but since this is within the 90% confidence interval the true variance is less than 4%.

One way scientists demonstrate bioequivalence is to measure the time it takes the generic drug to reach the bloodstream in 24 to 36 healthy, volunteers. This gives them the rate of absorption, or bioavailability, of the generic drug, which they can then compare to that of the innovator drug. The generic version must deliver the same amount of active ingredients into a patient's bloodstream in the same amount of time as the innovator drug.

All this means that a generic drug can be ready for approval in a matter of months, as opposed to the 10-15 years required to approve a new “innovator” drug.

Narrow therapeutic index

Although most medications have a wide margin of safety, a few "high-alert drugs" bare a heightened risk of causing injury when they are misused. Medications with a "narrow therapeutic index" - a very small therapeutic dose range above or below which could cause significant toxicity or sub-therapeutic levels—also bare an increased risk of causing injury when they are misused. Although errors may or may not be more common with these drugs than with others, their consequences may be more devastating. Examples of "high-alert drugs" or "narrow therapeutic index drugs" include monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, warfarin, oral hypoglycemic agents, insulin, digoxin, antiseizure medications and many cancer drugs.

The National Association of the Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) attempted to address this issue with the FDA via a letter they sent on March 18, 1997. The FDA's response on April 16, 1997 confirnmed that the FDA does not currently do anything to test differently for narrow therapeutic index drugs when establishing therapeutic equivalence and does not appear to have any intention to do so since they are only establishing guidelines and it is up to the states to establish exactly how regulated.

FDA rating system

The Orange Book uses Therapeutic Equivalence codes (TE codes) a short series of letters and sometimes numbers (eg AB, AB2, BX) to categorize drugs based upon their assessed equivalency. The first letter indicates that the FDA has either concluded a generic formulation is therapeutically equivalent to the reference drug (an “A” Code rating) or that the compared drugs are not equivalent (a “B” Code rating). The second letter provides additional information about the FDA compared formulations and testing procedures. According to the FDA, the ratings mean:

- for A-products that the FDA considers to be therapeutically equivalent to other pharmaceutically equivalent products; and

- for B-products that FDA considers not to be therapeutically equivalent to other pharmaceutically equivalent products.

Equivalence codes

Below is a short listing of the specific classifications for TE codes and what they mean.

The “A” rated subcodes

- AA – product in conventional dosage forms that are not regarded as presenting either actual or potential bioequivalence problems or drug quality or standards issues.

- AB - products having identical active ingredients(s), dosage form, and route(s) of administration and having the same strength.

- AN – solution and powders intended for aerosolization.

- AO – an injectable oil sulution where the drug, concentration, and oil used as a vehicle are all the same.

- AP – an injectable aqueous solution, in certain instance, intravenous nonaqueous solutions.

- AT – topical dosage forms including solutions, creams, ointments, gels, lotions, pastes, sprays and suppositories.

The “B” rated subcodes

- BC – extended release dosage forms (tablets, capsules, injections).

- BD – active ingredients and dosage forms with documented bioequivalence problems.

- BE – delayed release oral dosage forms (i.e., enteric coated)

- BN – products in aerosol / nebulizer drug delivery systems.

- BP – active ingredients and dosage forms with potential bioequivalence problems.

- BR – suppositories or enemas that deliver drugs for systemic absorption.

- BS – products having drug-standard deficiencies

- BT – topical products with bioequivalence issues.

- BX – products for which the data is insufficient to determine therapeutic equivalence.

- B* - requires further FDA investigation and review to determine therapeutic equivalence.

Authorized generics

Every subject, including generic drugs, have some controversial aspect to them. In the generic drug world, one of the more controversial practices is the sale of authorized generics. Authorized generics are prescription drugs produced by brand pharmaceutical companies and marketed under a private label, at generic prices.

Authorized generics compete with generics on price, quality and availability in the generic marketplace, and are marketed to consumers during and after what is commonly known as “the 180-day exclusivity period”. In June 2009 the FTC issued an Interim Report that found that drug prices are lower when authorized generics are marketed against a single generic drug than when they are not. The report showed that with authorized generic competition during the 180-day marketing exclusivity period, retail drug prices are on average 4.2 percent lower than the pre-generic branded price, and wholesale drug prices are on average 6.5 percent lower than the pre-generic branded price.

The true controversy of this situation is two-fold. First, authorized generics have a substantial effect on the revenues of competing generic firms. For instance, an authorized generic reduces the first filer's revenues by 40-52% during the 180-day exclusivity period and by 53-62% over the following 30 months. Second, there is strong evidence that agreements not to compete using authorized generics have become a way that some branded firms compensate generic firms. For example, in FY 2010, fifteen drug patent settlements combined an explicit agreement by the brand manufacturer not to launch an authorized generic competitor and a commitment by the first-filing generic to defer entry. This information also comes from the FTC's June 2009 Interim Report.

See also

Drug Price Competition and Patent-Term Restoration Act

Food and Drug Administration

References

- Orange Book Preface, http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/ucm079068.htm

- Wikipedia,Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Approved_Drug_Products_with_Therapeutic_Equivalence_Evaluations

- Generic Drugs Questions and Answers, http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/QuestionsAnswers/ucm100100.htm

- Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: Publications, http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/eclink.cfm

- Therapeutic Equivalence of Generic Drugs - Response to National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/AbbreviatedNewDrugApplicationANDAGenerics/ucm073224.htm

- Wikipedia, Authorized Generics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authorized_generics

- Orange Book Blog, Federal Trade Commission Issues Final Report on Authorized Generic Drugs, http://www.orangebookblog.com/authorized_generics/

- Federal Trade Commission, 2009 Interim Report, http://www.ftc.gov/os/2009/06/P062105authorizedgenericsreport.pdf