Federal pharmacy law

From Rx-wiki

For over a century, federal legislation has been impacting the practice of pharmacy. In almost every case, the purpose of this legislation has been to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the patient from the potential risks of drug use or misuse.

Most of this federal legislation has been initiated in response to issues and concerns at a certain point in time. For example, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FDC) Act passed by Congress was done as a safety concern because of the deaths of over 100 individuals who consumed a drug product containing antifreeze. Other acts that followed also were the result of significant issues with national implications.

While defining pharmacy practice and regulating the profession has primarily been left to the individual states based on the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution, the federal government regulates drug distribution through the Interstate Commerce Clause. This regulation of drug distribution often results, either directly or indirectly, in the regulation of the profession of pharmacy as well. The federal government also has implemented legislation affecting pharmacy practice based on participation in such programs as Medicaid. The counseling provisions of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, while not directly requiring pharmacist actions, did require the individual state governments to establish expanded standards of practice or risk losing federal funding of their programs. In effect, a back door approach to regulating the profession was utilized.

Over the years, much of the federal legislation that has been passed by Congress has proven itself useful by providing the safety and security that our society has come to expect. Pharmacists have embraced this legislation, albeit sometimes reluctantly, as most legislation has imposed new requirements in such areas as record keeping, counseling, and packaging of pharmaceuticals.

Contents

- 1 Creating a federal law

- 2 Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906

- 3 Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914

- 4 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938

- 5 Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951

- 6 Kefauver-Harris Amendment of 1962

- 7 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (with updates)

- 8 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970

- 9 Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970

- 10 Medical Device Amendments of 1976

- 11 Federal Antitampering Act of 1983

- 12 Orphan Drug Act of 1983

- 13 Drug Price Competition and Patent-Term Restoration Act of 1984

- 14 Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987

- 15 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987

- 16 Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990

- 17 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990

- 18 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994

- 19 Uruguay Round Agreements Act of 1994

- 20 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

- 21 Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997

- 22 2002 Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act

- 23 Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

- 24 Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005

- 25 Medicaid Tamper-Resistant Prescription Law of 2007

- 26 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010

- 27 See also

- 28 References

Creating a federal law

This is the legislative process as established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal administration in 1935.

Under our current systems we have two major routes in which federal legislation may become law:

- The U.S. Congress (House of Representatives and the Senate) passes a law stating objectives to met, or

- a federal agency decides to create or modify a regulation to meet a new situation.

Advanced notice of proposed rule making and/or the proposed rule is published in the Federal Register (FR). The Federal Register is the official journal of the federal government of the United States that contains most routine publications and public notices of government agencies. It is a daily publication excluding holidays.

After public viewing and discussion, any modifications to the rules are also published in the FR, and eventually the final rule will be published in the FR. Once a rule is made official it gets codified into the next edition of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). While new regulations are continually becoming effective, the printed volumes of the CFR are only issued annually.

Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906

The original Pure Food and Drug Act (also known as the Wiley Act) was passed by Congress on June 30, 1906 and signed by President Theodore Roosevelt. It prohibited interstate commerce in misbranded and adulterated foods, drinks and drugs under penalty of seizure of the questionable products and/or prosecution of the responsible parties.

To define a couple of terms, to misbrand something means to brand or label misleadingly or fraudulently; while, adulterated means to make impure by adding improper or inferior ingredients.

The Meat Inspection Act was also passed the same day.

Shocking disclosures of insanitary conditions in meat-packing plants, the use of poisonous preservatives and dyes in foods, and cure-all claims for worthless and dangerous patent medicines were the major problems (brought to the public's attention via journalists known as muckrakers) leading to the enactment of these laws. Two of the most famous muckrakers were a journalist named Samuel Hopkins Adams (whom wrote a series of eleven articles for Collier's Weekly, called “The Great American Fraud”) and an author and social activist named Upton Sinclair (whom wrote “The Jungle”)

The following are some important court cases involving the Pure Food and Drug Act:

- In 1911, the U.S. v. Johnson, the Supreme Court ruled that the 1906 Food and Drugs Act does not prohibit false therapeutic claims but only false and misleading statements about the ingredients or identity of a drug.

- In 1912, in reaction to the U.S. v. Johnson verdict, Congress enacted the Shirley Amendment to over come the ruling in U.S. v. Johnson. It prohibited labeling medicines with false therapeutic claims intended to defraud the purchaser, a standard difficult to prove.

- In 1924 in U.S. v. 95 Barrels Alleged Apple Cider Vinegar, the Supreme Court ruled that the Food and Drugs Act condemns every statement, design, or device on a product's label that may mislead or deceive, even if technically true. This case helped to verify the Pure Food and Drug Act's enforceability for dealing with misbranded and adulterated products.

This act is often considered the beginning of the FDA.

Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act was a United States federal law that regulated and taxed the production, importation, distribution and use of opiates. The act was proposed by Representative Francis Burton Harrison of New York and was approved on December 17, 1914 when it was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson.

"An act To provide for the registration of, with collectors of internal revenue, and to impose a special tax on all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations, and for other purposes."

This act was intended to curve the growing number of opium addictions within the U.S. As well as to deal with concerns over our new territory in the Philippines.

Following the Spanish-American War the U.S. took over government of the Philippines. Confronted with a licensing system for opium addicts, a Commission of Inquiry was appointed to examine alternatives to this system. The Brent Commission recommended that narcotics should be subject to international control.

This proposal was supported by the United States Department of State and in 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt called for an international opium conference, which was held in Shanghai in 1909. A second conference was held at the Hague in 1911, and out of it came the first international drug control treaty, the International Opium Convention of 1912, aimed primarily at solving the British-caused opium problems of China.

In 1914, the Senate considered the Harrison bill. The act was supported by the Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan who urged that the law be passed to fulfill the obligation of the new international treaty. The debate was about international obligations rather than morality.

The act appears to be concerned about the marketing of opiates. However a clause applying to doctors allowed distribution "in the course of his professional practice only." This clause was interpreted after 1917 to mean that a doctor could not prescribe opiates to an addict, since addiction was not considered a disease. A number of doctors were arrested and some were imprisoned. The medical profession quickly learned not to supply opiates to addicts.

The impact of diminished supply was obvious by mid-1915. A 1918 commission called for sterner law enforcement. Congress responded by tightening up the Harrison Act — the importation of heroin for any purpose was banned in 1924.

This act fell under the regulation of the IRS for tax collection and was enforced by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938

Because of the shortcomings of the 1906 Act, the FDA petitioned Congress for a new act. Between 1933 and 1937, a legislative battle ensued to replace the 1906 law. On one side of the battle were capitalists calling for laissez faire, on the other were social reformers fighting for government intervention due to concerns over public safety. Ultimately, it was a therapeutic disaster in 1937 that motivated Congress to act. A Tennessee company marketed a sulfa drug in an untested solvent (diethylene glycol) that resulted in the death of 107 people, many of whom were children. The public outcry not only reshaped the drug provisions of the new law to prevent such an event from happening again, but it propelled the bill through Congress.

After being passed by both houses of Congress it was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1938

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act contains the following new provisions:

- Extending control to cosmetics and therapeutic devices.

- Requiring new drugs to be shown safe before marketing-starting a new system of drug regulation.

- Eliminating the Shirley Amendment requirement to prove intent to defraud in drug misbranding cases.

- Providing that safe tolerances be set for unavoidable poisonous substances.

- Authorizing standards of identity, quality, and fill-of-container for foods.

- Authorizing factory inspections.

- Adding the remedy of court injunctions to the previous penalties of seizures and prosecutions.

This particular act is still the basis of the Food and Drug Administration's authority although it has received various amendments in the past 75 years. The major amendments include:

- Durham-Humphrey Amendment

- Kefauver Harris Amendment

- Medical Device Amendment

- Orphan Drug Act

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act

- Prescription Drug Marketing Act

- Dietary Supplements and Health Education Act

- Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act

- Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act

Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951

This amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, also known as the Prescription Drug Amendment, was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman on October 26, 1951. This amendment was co-sponsored by former vice president and senator Hubert H. Humphrey Jr., who was a pharmacist in South Dakota before beginning his political career. The other sponsor of this amendment was Carl Durham, a pharmacist representing North Carolina in the House of Representatives.

The Durham-Humphrey Amendment, enacted in 1951, resolved the issues left open by the 1938 Act. It established two classes of drugs: Rx legend (prescription) and OTC (over the counter). Prior to the passage of this amendment, drug manufacturers were generally free to determine in which category their drug belonged. A subsection of this amendment granted the FDA the authority to categorize prescription drugs as those that are habit-forming, unsafe for use except under the supervision of a health care practitioner, and/or subject to the new drug application approval process.

Additionally, under this amendment, a drug manufacturer can switch their product from Rx to OTC status by doing any one of the following:

- The drug manufacturer can request the switch by submitting a supplemental application.

- The drug manufacturer can petition the FDA for the switch

- And the primary mechanism for switching drugs to OTC is for the drug manufacturer to go through the OTC process, and a review board which the FDA would have to agree to.

If the FDA agrees, a final report switching from a prescription drug to OTC drug takes place.

The amendment also gave guidance as to what minimal information must be included on the prescription label:

- name and address of the pharmacy,

- serial number of the prescription,

- date of its filling,

- the name of the prescriber,

- the name of the patient,

- the directions for use, and

- any applicable warning labels.

Kefauver-Harris Amendment of 1962

From 1956 to 1962, approximately 10,000 children were born with severe malformities, including phocomelia, because their mothers had taken thalidomide during pregnancy. In 1962, in reaction to the tragedy, the United States Congress enacted the Kefauver-Harris Amendment.

Among other things, the amendment requires drug manufacturers to show the effectiveness of their products as well as their safety, to report adverse events to the FDA, and to ensure that their advertisements to physicians disclose the risks as well as the benefits of their products. Informed consent was required from participants in clinical studies. The FDA also was given jurisdiction over prescription drug advertising. In addition, the agency was required to approve a regulatory submission known as a new drug application before a company could market a new drug and be allowed to issue good manufacturing practice guidelines governing how drugs were to be manufactured. Inspection of drug manufacturers was mandated every 2 years.

The law was signed by President John F. Kennedy on October 10, 1962.

The Kefauver-Harris Amendment provided the modern scenario for approving new drugs:

- Initial drug discovery.

- Preclinical (animal) testing.

- An investigational new drug application (IND) outlines what the sponsor of a new drug proposes for human testing in clinical trials.

- Phase 1 studies (typically involve 20 to 80 healthy people).

- Phase 2 studies (typically involve a few dozen to about 300 people with the ailment that the new drug is intended to treat).

- Phase 3 studies (typically involve several hundred to about 3,000 people with the ailment that the new drug is intended to treat).

- The pre-NDA period, just before a new drug application (NDA) is submitted. A common time for the FDA and drug sponsors to meet.

- Submission of an NDA is the formal step asking the FDA to consider a drug for marketing approval.

- After an NDA is received, the FDA has 60 days to decide whether to file it so it can be reviewed.

- If the FDA files the NDA, an FDA review team is assigned to evaluate the sponsor's research on the drug's safety and effectiveness.

- The FDA reviews information that goes on a drug's professional labeling (information on how to use the drug).

- The FDA inspects the facilities where the drug will be manufactured as part of the approval process.

- FDA reviewers will approve the application or find it either "approvable" or "not approvable."

- Post marketing study commitments, also called Phase 4 commitments.

Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (with updates)

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was passed by Congress as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. And signed into law by President Richard Nixon on October 27, 1970.

Since the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act in 1914 many attempts had been made to strengthen government control and regulation of illicit substances with varying degrees of success. The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act is our countries most ambitious attempt to date and replaces similar legislation from the past including the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act.

The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act provides for the classification, acquisition, distribution, registration/verification of prescribers, and appropriate record keeping requirements of controlled substances. This act also provided the legal framework for the creation of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which is the organization primarily tasked with the enforcement responsibilities of the CSA.

To ensure an appropriate understanding of this law various updates will be included with discussion of this act.

Classification of controlled substances

Besides over the counter medications (OTC) such as aspirin and ibuprofen, behind the counter medications (BTC) such as Allegra-D (fexofenadine with pseudoephedrine), and prescription medications (Rx legend) such as amoxicillin and digoxin, there is another group of medications to be concerned with called controlled substances.

Controlled substances are medications with further restrictions due to abuse potential. There are 5 schedules of controlled substances with various prescribing guidelines based on abuse potential counter balanced by potential medicinal benefit as determined by the Drug Enforcement Administration and individual state legislative branches. The DEA is provided with this authority by the Controlled Substances Act. Below is a brief explanation of the schedules along with example medications.

Schedule I (CI)

- Characteristics:

- Unaccepted medical use.

- Highest potential for abuse.

- Not available by a prescription.

- Examples:

- LSD

- heroin

- Quaaludes (methaqualone)

Schedule II (CII)

- Characteristics:

- High potential for abuse or misuse.

- Sufficient medicinal use to justify availability as a prescription.

- Examples:

- oxycodone

- morphine

- amphetamines

Schedule III (CIII)

- Characteristics:

- Potential risk for abuse, misuse, and dependence.

- Examples:

- Vicodin (hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen)

- Codeine and codeine containing products in a solid dosage form (tablet, capsule, etc.).

Schedule IV (CIV)

- Characteristics:

- Low potential for abuse and limited risk of dependence.

- Examples:

- phenobarbital

- benzodiazepines

- other sedatives and hypnotics

Schedule V (CV)

- Characteristics:

- Low potential for abuse or misuse.

- Examples:

- Cough medicines that contain a limited amount of codeine.

- Antidiarrheal medications that contain a limited amount of an opiate such as Lomotil (diphenoxylate and atropine).

Many problems associated with drug abuse are the result of legitimately-manufactured controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into the illicit drug traffic. Many of the narcotics, depressants and stimulants manufactured for legitimate medical use are subject to abuse, and have therefore been brought under legal control. The goal of controls is to ensure that these "controlled substances" are readily available for medical use, while preventing their distribution for illicit sale and abuse.

Purchasing

Controlled substances require special consideration when it comes to purchasing.

Schedule III – V drugs may be ordered by a pharmacy or other appropriate dispensary on a general order from a wholesaler and you should check the delivery in against the original order.

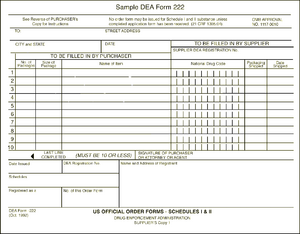

The DEA form 222 is a triplicate form. The pharmacy retains the third sheet while sending the first and second pages to the wholesaler. The wholesaler is responsible for sending the second page to the DEA while retaining the first page for its own records. When the Schedule II medications arrive in the pharmacy they should be checked in against the DEA form.

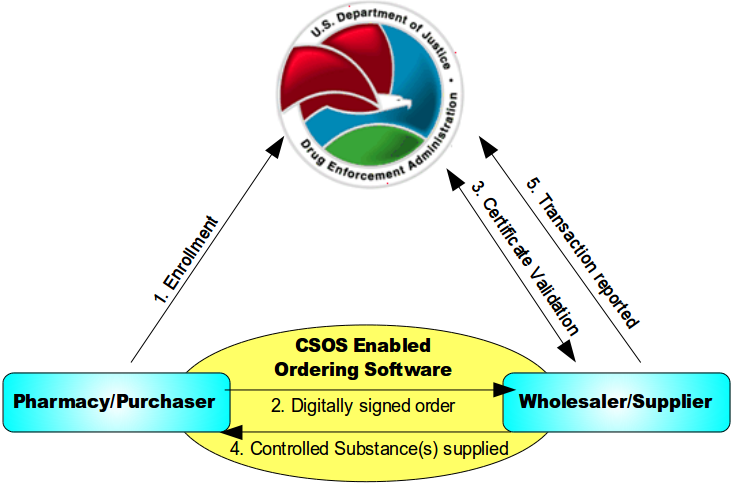

Below is an image explaining how ordering schedule II medications work with a controlled substances ordering system (CSOS)

- An individual enrolls with the DEA and, once approved, is issued a personal CSOS Certificate.

- The purchaser creates an electronic 222 order using an approved ordering software. The order is digitally signed using the purchaser's personal CSOS Certificate and then transmitted to the suppliers. The paper 222 is not required for electronic ordering.

- The supplier receives the purchase order and verifies that the purchaser's certificate is valid with the DEA. Additionally, the supplier validates the electronic order information just like it would a paper order.

- The supplier completes the order and ships to the purchaser. Any communications regarding the order are sent electronically.

- The order is reported by the supplier to the DEA within two business days.

Recieving

When the pharmacy receives controlled substances they should be carefully checked in against the purchase order including product name, quantity, strength, and package size. Controlled substances are shipped in separate containers from the rest of the pharmacy order and should be checked in by a pharmacist, although pharmacy technicians may assist with this process under the direct supervision of a pharmacist. Schedule II medications need to be checked in against your DEA 222 form (whether the paper triplicate form, or the electronic form on your CSOS enabled software).

Schedule II medications may be stocked separately in a secure place or disbursed throughout the stock. Their stock must be continually monitored and documented.

You may store CIII – CV medications in one of two ways:

- In a secured vault or,

- Dispersed throughout the pharmacy stock. By dispersing the stock through out, you effectively prevent someone from being able to obtain all your controlled substances since they can not do easy "One stop shopping."

Controlled substances prescriptions

Controlled substances have some additional things to keep in mind when reviewing prescription orders. All controlled substance prescriptions require the prescriber to include their DEA number on the prescription. While traditional prescriptions are good for one year from the date they are written and (at the prescriber's discretion) may have a sufficient number of refills to cover an entire one year supply; controlled substances have some differences based on which schedule they are. Schedule V medications may be refilled for up to a one year supply like prescriptions for non-controlled substances. Schedule III-IV medications may be written for up to a six month supply of medications including any refills on the original prescription. Schedule II medications may be written for up to a 90 day supply but may not include any refills. If a patient has a 30 day limit from their insurance the physician would need to write three separate prescriptions for thirty days to cover the full 90 days. Prescribers are not allowed to exceed a 90 day supply of a schedule II medications with out seeing the patient again.

Telephone orders and facsimiles

Pharmacies may accept telephone orders and faxes for schedule III-V medications. The pharmacist must immediatley reduce telephone order prescriptions to writing. Schedule II medications may not be ordered over the phone or via a fax machine under ordinary circumstances.

DEA has granted three exceptions to the facsimile prescription requirements for Schedule II controlled substances. The facsimile of a Schedule II prescription may serve as the original prescription as follows:

- A practitioner prescribing Schedule II narcotic controlled substances to be compounded for the direct administration to a patient by parenteral, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous or intraspinal infusion may transmit the prescription by facsimile. The pharmacy will consider the facsimile prescription a "written prescription" andno further prescription verification is required.All normal requirements of a legal prescription must be followed.

- Practitioners prescribing Schedule II controlled substances for residents of Long Term Care Facilities (LTCF) may transmit a prescription by facsimile to the dispensing pharmacy. The practitioner’s agent may also transmit the prescription to the pharmacy. The facsimile prescription serves as the original written prescription for the pharmacy.

- A practitioner prescribing a Schedule II narcotic controlled substance for a patient enrolled in a hospice care program certified and/or paid for by Medicare under Title XVIII or a hospice program which is licensed by the state may transmit a prescription to the dispensing pharmacy by facsimile. The practitioner or the practitioner’s agent may transmit the prescription to the pharmacy. The practitioner or agent will note on the prescription that it is for a hospice patient. The facsimile serves as the original written prescription.

For Schedule II controlled substances, an oral order is only permitted in an emergency situation. An emergency situation is defined as a situation in which:

- Immediate administration of the controlled substance is necessary for the proper treatment of the patient.

- No appropriate alternative treatment is available.

- Provision of a written prescription to the pharmacist prior to dispensing is not reasonably possible for the prescribing physician.

In an emergency, a practitioner may call-in a prescription for a Schedule II controlled substance by telephone to the pharmacy, and the pharmacist may dispense the prescription provided that the quantity prescribed and dispensed is limited to the amount adequate to treat the patient during the emergency period. The prescribing practitioner must provide a written and signed prescription to the pharmacist within seven days. Further, the pharmacist must notify DEA if the prescription is not received.

E-prescribing

The regulations concerning electronic transmission of controlled substances via e-prescribing recently changed. As of June 1, 2010 physicians and pharmacies are now allowed to transmit prescriptions for Schedule II, III, IV, and V medications as long as they are using properly certified software (i.e., SureScripts). While this is a recent shift in federal law, some states may still prohibit e-prescribing for controlled substances.

Partial fill of prescriptions

Pharmacists often question the DEA rule regarding the partial refilling of Schedule III, IV, or V prescriptions. Confusion lies in whether or not a partial fill or refill is considered one fill or refill, or if the prescription can be dispensed any number of times until the total quantity prescribed is met or 6 months has passed. According to the DEA's interpretation, as long as the total quantity dispensed meets with the total quantity prescribed with the refills, and they are dispensed within the 6-month period, the number of refills is irrelevant.

The Code of Federal Regulations states that the partial filling of a prescription for a controlled substance listed in Schedule III, IV, or V is permissible, provided that:

- Each partial filling is recorded in the same manner as a refilling.

- The total quantity dispensed in all partial fillings does not exceed the total quantity prescribed.

- No dispensing occurs after 6 months of the date on which the prescription was issued.

For a Schedule II drug, the pharmacist may partially dispense a prescription if he or she is unable to supply the full quantity in a written or emergency oral prescription, provided the pharmacist notes the quantity supplied on the front of the prescription. The remaining portion must be supplied within 72 hours of the first partial dispensing. Otherwise, the pharmacist is obligated to notify the prescribing physician of the shortage.

Transferring prescriptions

The DEA allows the transfer of original prescription information for Schedule III, IV, and V controlled substances for the purpose of refill dispensing between pharmacies on a one-time basis. Pharmacies which electronically share a real-time, online database may transfer up to the maximum number of refills permitted by the law and authorized by the prescriber. In either type of transfer, specific information must be recorded by both the transferring and the receiving pharmacist.

DEA number verification

Many problems associated with drug abuse are the result of legitimately-manufactured controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into the illicit drug traffic. Many of the narcotics, depressants and stimulants manufactured for legitimate medical use are subject to abuse, and have therefore been brought under legal control. The goal of controls is to ensure that these "controlled substances" are readily available for medical use, while preventing their distribution for illicit sale and abuse.

Under federal law, all businesses which manufacture or distribute controlled drugs, all health professionals entitled to dispense, administer or prescribe them, and all pharmacies entitled to fill prescriptions must register with the DEA. Authorized registrants receive a "DEA number". Registrants must comply with a series of regulatory requirements relating to drug security, records accountability, and adherence to standards.

A DEA number is a series of numbers assigned to a health care provider (such as a dentist, physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) allowing them to write prescriptions for controlled substances. Legally the DEA number is solely to be used for tracking controlled substances. The DEA number, however, is often used by the industry as a general "prescriber" number that is a unique identifier for anyone who can prescribe medication.

A valid DEA number consists of:

- 2 letters and 7 digits

- The first letter is always an A (deprecated), B (most common), or F (new) for a dispenser. (Also M is available for mid-level practitioners in some states and either P or R is used for a wholesaler)

- The second letter is typically the initial of the registrant's last name

- The seventh digit is a "checksum" that is calculated as:

- Add together the first, third and fifth digits

- Add together the second, fourth and sixth digits and multiply the sum by 2

- Add the above 2 numbers

- The last digit (the ones value) of this last sum is used as the seventh digit in the DEA number

Record keeping requirements

Every pharmacy must maintain complete and accurate records on a current basis for each controlled substance purchased, received, distributed, dispensed, or otherwise disposed of. These records must be maintained for 2 years. It is also required that records and inventories of Schedule II and Schedule III, IV, and V drugs must be maintained separately from all other records or be in a form that is readily retrievable from other records. The "readily retrievable" requirement means that records kept by automatic data processing systems or other electronic means must be capable of being separated out from all other records in a reasonable time. In addition, some notation, such as a 'C' stamp, an asterisk, red line, or other visually identifiable mark must distinguish controlled substances from other items.

Inventory requirements

A pharmacy is required by the DEA to take an inventory of controlled substances every 2 years (biennially). This inventory must be done on any date that is within 2 years of the previous inventory date. The inventory record must be maintained at the registered location in a readily retrievable manner for at least 2 years for copying and inspection by the Drug Enforcement Administration. An inventory record of all Schedule II controlled substances must be kept separate from those of other controlled substances. Submission of a copy of any inventory record to the DEA is not required unless requested.

When taking the inventory of Schedule II controlled substances, an actual physical count must be made. For the inventory of Schedule III, IV, and V controlled substances, an estimate count may be made. If the commercial container holds more than 1000 dosage units and has been opened, however, an actual physical count must be made.

Theft or loss of controlled substances

In the event that controlled substances are stolen, or are found to be missing a pharmacy should:

- contact the local police and the DEA,

- fill out and file DEA form 106.

The DEA form 106 is available as both a printed form, or may be filed electronically. To obtain the printed form click here and printout the PDF. To file elctronically proceed to https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/webforms/dtlLogin.jsp .

The DEA requires that theft of controlled substances must be reported within 24 hours.

State regulations

Many states have additional regulations for controlled substances. It is a necessary to know the differences that exist in your state. Some examples include:

- Some states have made additional drugs scheduled medications such as the following states have made carisoprodol a controlled substance:

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Indiana

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- Nevada

- New Mexico

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Texas

- West Virginia

- Many states, such as Pennsylvania, treat schedule V prescriptions the same as schedule III and IV prescriptions with regards to refill limits and totally quantity that may be prescribed at a time.

- Various states, such as New York, limit schedule II prescriptions to a 30 day supply.

- Some states, such as Pennsylvania, currently do not allow e-prescribing of schedule II medication.

Be aware of the differences with regards to controlled substances in the states you practice in and remember that the expectation when state and federal law appear to be in conflict is that you will follow the stricter regulation.

Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 was signed into law on December 29, 1970 by President Richard M. Nixon, and it created both the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). This act is intended to prevent work-related injuries, illnesses and deaths by issuing and enforcing rules (called standards) for workplace safety and health.

Since its inception, workplace fatalities have been cut by 77% and workplace injuries have declined 55% while employment has doubled from 56 million workers at 3.5 million work-sites to 115 million workers at nearly 7 million work-sites

The portions that most strongly impact pharmacy are:

- Written hazard communication program

- Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS)

- Air contaminants

- Flammable and combustible liquids

- General concerns about hazardous materials

The act provides stern enforcement policies with fines up to $10,000 for instances where employers “willfully” expose workers to “serious” harm or death. Any act of criminal negligence can result in imprisonment of up to six months.

Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970

The Poison Prevention Packaging Act (PPPA) of 1970 was signed into law on December 30, 1970 by President Richard M. Nixon. Before the PPPA was enacted poisonings by common household substances, including medicines, had long been considered by pediatricians to be the leading cause of injuries among children under 5 years of age. After the PPPA and the implementation of standards to prevent poisonings, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) reported that child-resistant packaging reduced the oral prescription medicine-related death rate by up to 1.4 deaths per million children under age 5 years. This represented a reduction in the rate of fatalities of up to 45% from levels that would have been projected in the absence of child-resistant packaging requirements, and equated to about 24 fewer child deaths annually.

The purpose of the PPPA was to give to the CPSC authority to require "special packaging" of household products and drugs to protect children from serious injury or illness. Manufacturers are required to perform tests to ensure that children under 5 years of age would find the packaging significantly difficult to open. In these tests, pairs of children aged 42 to 51 months are selected and given 5 minutes in which to open the packages. If the children cannot open the package, they are then given a visual demonstration and another 5 minutes in which to open the package. The package is considered to be child-resistant if not more than 20% of the 200 children tested can open the package. Adults are also tested with the same packages. Adults are likewise given a 5-minute period to open and properly close the package. If 90% of the 100 adults tested can open and close the child-resistant package, it passes.

The PPPA affects pharmacy practice and manufacturing of OTC and prescription medications in many ways. Failure to comply with packaging requirements or any of the applicable regulations is considered a misbranding violation under the FDC Act. A pharmacist could be prosecuted and imprisoned for not more than 1 year or sentenced to pay a fine of not more than $1000, or both.

All legend drugs and controlled dangerous substances must be packaged in a child-resistant container, with limited exceptions. Pharmacists should be familiar with their responsibilities under the PPPA . OTC products also require child-resistant packaging, with one exception. Manufacturers may market one size of an OTC product for the elderly or handicapped in noncompliant containers, provided that the package states, "This Package for Households Without Young Children."

Exceptions to child-resistant packaging for prescription drugs

- Patient requests non-child-resistant packaging.

- Physician requests non-child-resistant packaging.

- Sublingual dosage forms of nitroglycerin.

- Sublingual and chewable forms of isosorbide dinitrate in dosage strengths of 10 mg or less.

- Erythromycin ethylsuccinate granules for oral suspension and oral suspensions in packages containing not more than 8 grams of the equivalent of erythromycin.

- Cyclically administered oral contraceptives in manufacturers' mnemonic (memory-aid) dispenser packages that rely solely upon the activity of one or more progestogen or estrogen substances.

- Anhydrous cholestyramine in powder form.

- All unit dose forms of potassium supplements, including individually-wrapped effervescent tablets, unit dose vials of liquid potassium, and powdered potassium in unit-dose packets, containing not more than 50 milliequivalents of potassium per unit dose.

- Sodium fluoride drug preparations including liquid and tablet forms, containing not more than 110 milligrams of sodium fluoride (the equivalent of 50 mg of elemental fluoride) per package or not more than a concentration of 0.5 percent elemental fluoride.

- Betamethasone tablets packaged in manufacturers' dispenser packages, containing no more than 12.6 milligrams betamethasone.

- Pancrelipase preparations in tablet, capsule, or powder form.

- Prednisone in tablet form, when dispensed in packages containing no more than 105 mg.

- Mebendazole in tablet form in packages containing not more than 600 mg.

- Methylprednisolone in tablet form in packages containing not more than 84 mg.

- Colestipol in powder form in packages containing not more than 5 grams of the drug.

- Erythromycin ethylsuccinate tablets in packages containing no more than the equivalent of 16 grams erythromycin.

- Conjugated Estrogens Tablets, U.S.P., when dispensed in mnemonic packages containing not more than 32.0 mg of the drug.

- Norethindrone Acetate Tablets, U.S.P., when dispensed in mnemonic packages containing not more than 50 mg of the drug.

- Medroxyprogesterone acetate tablets.

- Sacrosidase (sucrase) preparations in a solution of glycerol and water.

- Hormone Replacement Therapy Products that rely solely upon the activity of one or more progestogen or estrogen substances.

- Products intended for topical application.

- Products in dosage forms not intended for oral administration.

Pharmacist guidelines and responsibilities under the PPPA

- The pharmacist is responsible for ensuring packaging of required drugs in child-resistant containers.

- Prescription drugs provided by the manufacturer in child-resistant containers may be dispensed directly to the patient in that container.

- In general, plastic vials, which have previously been dispensed to the patient, cannot be reused for refills.

- Institutionalized patients are not required to receive child-resistant containers, but drugs for home use must comply with the PPPA.

- The CPSC recommends that pharmacists obtain a written authorization from patients for conventional packaging, although such is not a requirement.

Medical Device Amendments of 1976

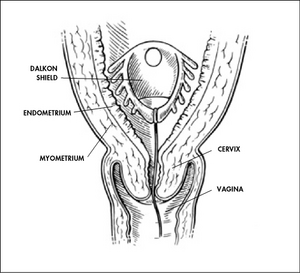

The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 were signed by President Gerald R. Ford on May 28, 1976. This is an amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938.While the Cooper Committee recommendations were being debated in Congress during 1972 and 1973, pacemaker failures were reported. And in 1975, hearings took place on problems that had been reported with the Dalkon Shield intrauterine device, which caused thousands of reported injuries. Those two incidents helped underscore the need for the Medical Device Amendments, enacted in 1976.

President Ford, in signing the law, said, "The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 eliminate the deficiencies that accorded FDA 'horse and buggy' authority to deal with 'laser age' problems." He added, "I welcome this legislation and commend the FDA, who identified the need, cooperated in its development, and finally, will be entrusted with its enforcement."

The 1976 amendments defined devices similarly to drugs, but noted that drugs cause a chemical reaction in the body, whereas devices do not. They called for all devices to be divided into classes, with varying amounts of control required in each one.Tongue depressors, for example, would fall under general controls of the types already existing (Class I); wheelchairs would be subjected to performance standards when general controls were deemed insufficient to assure product safety and effectiveness (Class II); while artificial hearts would be required to go through pre-market approval (Class III). The agency's first device performance standard was developed for impact-resistant lenses in eyeglasses and sunglasses.

The final provisions of the 1976 amendments closely resemble the Cooper Committee recommendations. In addition to the medical device inventory and classification requirements, Class III device manufacturers were required to notify the FDA prior to marketing. New devices that were substantially equivalent to pre-1976 devices could be marketed immediately, subject to any existing or future requirements for that type of device.

Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations also were authorized at that time. These are a set of procedures to ensure that devices are manufactured to be safe and effective through quality design, manufacture, labeling, testing, storage, and distribution.

Federal Antitampering Act of 1983

In the early morning of Wednesday, September 29, 1982, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman of Elk Grove Village died after taking a capsule of Extra Strength Tylenol. Adam Janus of Arlington Heights died in the hospital shortly thereafter. His brother, Stanley (of Lisle), and his wife Theresa died after gathering to mourn, taking pills from the same bottle. By October 1, 1982, the poisoning had also taken the lives of Paula Prince of Chicago, Mary Reiner of Winfield, and Mary McFarland of Elmhurst. Investigators soon discovered the Tylenol link. Urgent warnings were broadcast, and police drove through Chicago neighborhoods issuing warnings over loudspeakers.

As the tampered bottles came from different factories, and the seven deaths had all occurred in the Chicago area, the possibility of sabotage during production was ruled out. Instead, the culprit was believed to have entered various supermarkets and drug stores over a period of weeks, pilfered packages of Tylenol from the shelves, adulterated their contents with solid cyanide compound at another location, and then replaced the bottles. In addition to the five bottles which led to the victims deaths, three other tampered bottles were discovered.

Johnson & Johnson, the parent company of McNeil, distributed warnings to hospitals and distributors and halted Tylenol production and advertising. On October 5, 1982, it issued a nationwide recall of Tylenol products; an estimated 31 million bottles were in circulation, with a retail value of over $100 million. The company also advertised in the national media for individuals not to consume any products that contained Tylenol. When it was determined that only capsules were tampered with, they offered to exchange all Tylenol capsules already purchased by the public with solid tablets.

The perpetrator has never been caught, but the incident led to reforms in the packaging of over-the-counter substances and to federal anti-tampering laws.

Orphan Drug Act of 1983

Thirty-one years ago (in 1980), Abbey Meyers was at her wit's end. Her young son, who had Tourette's syndrome, had been cut off from the drug pimozide, which had begun to show promise in treating his debilitating condition. The doctor running the clinical trial told her the study was halted when McNeil Laboratories pulled out of producing the drug because it proved ineffective against schizophrenia, its primary (and more common) target. He told Meyers that pimozide would now be considered an "orphan drug," the term for products that target too few patients to bring in big bucks.

Now, her son's rare disorder was essentially untreatable. There was no recourse for the Connecticut housewife. "I was devastated," she says.

Drug research needed to be done on this disease, but the number of patients with Tourette's syndrome were so few that research was very cost prohibitive. With this and concerns over other rare diseases the Orphan Drug Act was enacted on January of 1983

An orphan drug is any drug developed under the Orphan Drug Act of January 1983 ("ODA"), a federal law concerning rare diseases ("orphan diseases"), defined as diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States or low prevalence is taken as prevalence of less than 5 per 10,000 in the community.

Because medical research and development of drugs to treat such diseases is financially disadvantageous, companies that do so are rewarded with tax reductions and marketing exclusivity, or a monopoly, on that drug for an extended time (seven years post-approval). The concept behind the ODA is that the longer period of exclusivity will encourage more companies to invest money in research. Under the act many drugs have been developed, including drugs to treat glioma, multiple myeloma, cystic fibrosis, and snake venom. In the US, from January 1983 to October 2008, a total of 1,800 different orphan drug designations have been granted by the Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD) and 325 orphan drugs have received marketing authorization in the US. In contrast, the decade prior to 1983 saw fewer than ten such products come to market.

Since few markets would naturally exist to create these goods, as the costs of developing, researching and producing these drugs would likely exceed any revenues, government intervention is required, usually to establish such a market or to produce the goods itself. Critics of the free market often cite this as a market failure in free market economic systems. Free market advocates often respond that without government intervention development costs would be considerably lower.

The intervention by government can take a variety of forms:

- Tax benefits to companies who produce or research these drugs.

- Granting of additional rights above and beyond those granted by the regular patent laws.

- Subsidizing and funding clinical research by universities and industry sponsors to develop medical products (including drugs, biological products, devices, and medical foods) for rare diseases.

- Creating a government-run company to research and produce drugs.

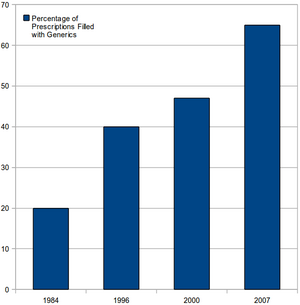

Drug Price Competition and Patent-Term Restoration Act of 1984

Hatch-Waxman amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. It sets forth the process by which would-be marketers of generic drugs can file Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to seek FDA approval of the generic. It allows 180 day exclusivity to companies that are the "first-to-file" an ANDA against holders of patents for branded counterparts.

The FDA will consider a generic product equivalent to a brand drug when both the rate and extent of absorption are not significantly different when administered in the same dose of therapeutic ingredient under similar experimental conditions in studies. The FDA has established specific statistical standards to make a determination of bioequivalence.

The Hatch-Waxman Act grants generic manufacturers standing to mount a validity challenge without incurring the cost of entry or risking enormous damages flowing from any possible infringement. Hatch-Waxman essentially redistributes the relative risk assessments and explains the flow of settlement funds and their magnitude. Hatch-Waxman gives generics considerable leverage in patent litigation: the exposure to liability amounts to litigation costs, but pales in comparison to the immense volume of generic sales and profits.

The other significant factor affecting the pharmaceutical industry was an increase in the length of time for a drug patent to expire from 12 years to 17 years (since then the URAA has extended it to 20 years). This extension was intended to off-set the time it took for a drug to be approved to provide adequate time for the original innovator companies to recoup their initial research investments and make a profit.

Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987

The Prescription Drug Marketing Act (PDMA), which was incorporated into the FDCA, was enacted to address certain prescription drug–marketing practices that have contributed to the diversion of large quantities of such drugs into a secondary gray market. These marketing practices—including the distribution of free samples and the sale of deeply discounted drugs to hospitals and health care entities—have helped fuel a multi million dollar drug diversion market that provides a portal through which mislabeled, subpotent, adulterated, expired, and counterfeit drugs are able to enter the nation's drug distribution system.

The most simple and straightforward of the acts which severely impacts pharmacy and is prohibited by the PDMA is the act or offer of knowingly selling, purchasing, or trading a prescription drug sample. This offense is punishable by a fine of up to $250,000 and up to 10 years' imprisonment. What many pharmacists do not realize is that there is a "finder's fee" of up to $125,000 for individuals who provide information leading to the conviction of a violator of this portion of the PDMA.

Another important portion of this extensive law that affects pharmacists prohibits the resale of any prescription drug that was previously purchased by a hospital or other "health care entity." This provision was intended to eliminate a major source of drugs in the diversion market-namely, drugs that were originally purchased by hospitals or health care entities at substantially discounted prices, as allowed by the Nonprofit Institutions Act of 1938, and then resold to the retail class of trade. Congress believed that the resale of such drugs constituted an unfair form of competition. Unfortunately, due to the host of exemptions found in the PDMA and the complexity and potential loopholes, prosecution of institutional diversion cases has been rare.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987

On December 22, 1987, President Ronald Reagan signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA-87) also known as the Federal Nursing Home Reform Act. This was enacted to protect the rights of patients in long-term care facilities such as nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living homes. This act gave the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) the authority to enact key measures to reduce unnecessary costs while improving the quality of patient care in these facilities.

Prior to the passage of this act there were many patient treatment practices that are considered unethical by today's standards; including

- routine orders for all patients to receive antidepressants without diagnosis of an appropriate condition,

- lack of routine monitoring of medication therapy, and

- frequent use of patient restraints (physical and chemical) at medically unnecessary times.

Some of the most important resident provisions in OBRA-87 include:

- Emphasis on a resident’s quality of life as well as the quality of care;

- New expectations that each resident’s ability to walk, bathe, and perform other activities of daily living will be maintained or improved absent medical reasons;

- A resident assessment process leading to development of an individualized care plan 75 hours of training and testing of paraprofessional staff;

- Rights to remain in the nursing home absent non-payment, dangerous resident behaviors, or significant changes in a resident’s medical condition;

- New opportunities for potential and current residents with mental retardation or mental illnesses for services inside and outside a nursing home;

- A right to safely maintain or bank personal funds with the nursing home; Rights to return to the nursing home after a hospital stay or an overnight visit with family and friends The right to choose a personal physician and to access medical records;

- The right to organize and participate in a resident or family council;

- The right to be free of unnecessary and inappropriate physical and chemical restraints;

- Uniform certification standards for Medicare and Medicaid homes;

- Prohibitions on turning to family members to pay for Medicare and Medicaid services; and

- New remedies to be applied to certified nursing homes that fail to meet minimum federal standards.

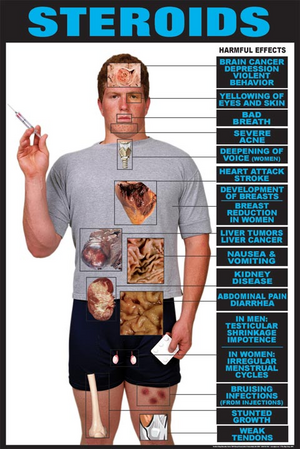

Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990

Anabolic steroids are defined as synthetic derivatives of the male hormone testosterone, having pronounced anabolic properties and relatively weak andronergic properties (i.e., producing masculine characteristics), which are used clinically mainly to promote growth and to repair body tissue in senility, debilitating illness, and convalescence. Anabolic steroids may also be referred to as andronergic-anabolic steroids.The intent of the ASCA is to minimize (or eliminate) the use of anabolic steroids for non-medical purposes. Prior to the ASCA, anabolic steroids were regulated as drugs pursuant to the FDCA.

The DEA has classified anabolic steroids as Schedule III controlled substances; however, certain products which are considered to have no significant potential for abuse because of their concentration, preparation, mixture, or delivery system, are exempt from being classified as control substances (such as Premarin with methyltestosterone tablets).

In addition, the classification does not include anabolic steroids expressly intended for cattle or other non-human species and which are approved by the FDA. However, prescribing, dispensing or distributing such substances for other than implantation in cattle or other non-human species is a violation of the law.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990

While most federal laws provide the pharmacist with guidance on handling pharmaceuticals, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90) placed expectations on the pharmacist in how to interact with the patient. While the primary goal of OBRA-90 was to save the federal government money by improving therapeutic outcomes, the method to achieve these savings was implemented by imposing on the pharmacist counseling obligations, prospective drug utilization review (ProDUR) requirements, and record-keeping mandates.

The OBRA-90 ProDUR language requires state Medicaid provider pharmacists to review Medicaid recipients' entire drug profile before filling their prescription(s). The ProDUR is intended to detect potential drug therapy problems. Computer programs can be used to assist the pharmacist in identifying potential problems. It is up to the pharmacists' professional judgment, however, as to what action to take, which could include contacting the prescriber. As part of the ProDUR, the following are areas for drug therapy problems that the pharmacist must screen:

- Therapeutic duplication

- Drug–disease contraindications

- Drug–drug interactions

- Incorrect drug dosage

- Incorrect duration of treatment

- Drug–allergy interactions

- Clinical abuse/misuse of medication

OBRA-90 also required states to establish standards governing patient counseling. In particular, pharmacists must offer to discuss the unique drug therapy regimen of each Medicaid recipient when filling prescriptions for them. Such discussions must include matters that are significant in the professional judgment of the pharmacist. The information that a pharmacist may discuss with a patient is found in the enumerated list below.

- Name and description of the medication.

- Dosage form, dosage, route of administration, and duration of drug therapy.

- Special directions and precautions for preparation, administration, and use by the patient.

- Common severe side effects or adverse effects or interactions and therapeutic contraindications that may be encountered.

- Techniques for self-monitoring of drug therapy.

- Proper storage.

- Refill information.

- Action to be taken in the event of a missed dose.

Under OBRA-90, Medicaid pharmacy providers also must make reasonable efforts to obtain, record, and maintain certain information on Medicaid patients. This information, including pharmacist comments relevant to patient therapy, would be considered reasonable if an impartial observer could review the documentation and understand what has occurred in the past, including what the pharmacist told the patient, information discovered about the patient, and what the pharmacist thought of the patient's drug therapy. Information that would be included in documented information are listed below.

- Name, address, and telephone number.

- Age and gender.

- Disease state(s) (if significant)

- Known allergies and/or drug reactions.

- Comprehensive list of medications and relevant devices.

- Pharmacist's comments about the individual's drug therapy.

While OBRA-90 was geared to ensure that Medicaid patients receive specific pharmaceutical care, the overall result of the legislation provided that the same type of care be rendered to all patients, not just Medicaid patients. The individual states did not establish 2 standards of pharmaceutical care-one for Medicaid patients and another for non-Medicaid patients. The end result is that all patients are under the same professional care umbrella requiring ProDUR, counseling, and documentation.

Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994

A dietary supplement is defined under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) as a product that is intended to supplement the diet and bears or contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients:

- a vitamin

- a mineral

- an herb or other botanical (excluding tobacco)

- an amino acid

- a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake, or

- a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination of any of the above

Furthermore, it must be:

- intended for ingestion in pill, capsule, tablet, powder or liquid form

- not represented for use as a conventional food or as the sole item of a meal or diet

- labeled as a "dietary supplement"

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) was signed by President Clinton on October 25, 1994. Pursuant to the DSHEA, the Food and Drug Administration regulates dietary supplements as foods, and not as drugs. The FDA does not approve dietary supplements based on their safety and efficacy; the FDA can take action only after a dietary supplement has been proven harmful. However, certain foods (such as infant formula and medical foods) are deemed special nutritionals because they are consumed by highly vulnerable populations and are thus regulated more strictly than the majority of dietary supplements. The FDA claims that their rationale for a lack of regulation is a "freedom to choose" by the consumer, but there are economic benefits as well. The FDA chooses not to regulate dietary supplements because clinical trials are lengthy and costly. They tend to believe that the supplement is beneficial until problems arise.

Some interesting facts about dietary supplements include:

- It has been estimated that 40% of the US population uses dietary supplements often and that almost twice as many have used at least 1 of the estimated 29,000 dietary supplements on the market.

- Although most consumers of alternative therapies also take prescription medications, one survey found that 72% of respondents who used alternative therapies did not report that use to their health care providers. Despite their widespread use, health care providers often fail to ask patients about their use of these substances when asked about their current use of medications.

- In 1993, dietary supplement out-of-pocket expenditures were at $4.1 billion (up slightly from 1992's $3.9 billion expenditure); but after DSHEA was implemented, 1994 expenditures on dietary supplements nearly doubled to $8.1 billion.

- Finding reliable and unbiased information on herbal remedies continues to be a challenge, yet out-of-pocket expenditures on dietary supplements exceeded $22 billion in 2007 (accurate numbers for more recent years have not yet been made available).

Uruguay Round Agreements Act of 1994

The word patent originates from the Latin patere, which means “to lay open” (i.e., to make available for public inspection). A patent makes an invention viewable by the public, but also ensures a limited monopoly to the creator. From when a patent is granted, till it expires no one else is allowed to make anything that requires your patent without your express permission.

The Uruguay Round Agreement Act (URAA) was signed by President Clinton on December 8, 1994; which had an impact on a number of intellectual property laws. The part that impacts pharmacy the most is it extending patents to 20 years from the date of filing (prior to this it was 17 years under the Hatch-Waxman Act).

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) imposes 5 key provisions upon pharmacies.

- The first provision is the requirement that each pharmacy take reasonable steps to limit the use of, disclosure of, and the requests for PHI. PHI is defined as individually identifiable health information transmitted or maintained in any form and via any medium. To be in compliance, a pharmacy must implement reasonable policies and procedures that limit how PHI is used, disclosed, and requested for certain purposes. The pharmacy also is obligated to post its entire notice of privacy practices at the facility in a clear and prominent location and on its Web site (if one exists).

- The second component of HIPAA requires that individuals be informed of the privacy practices of the pharmacy and that the pharmacy develop and distribute a notice with a clear explanation of these rights and practices. This notice must be given to every individual no later than the date of the first service provided, which usually means the first prescription dispensed to the patient. The pharmacist also is obligated to make a good-faith effort to obtain the patient's written acknowledgment of the receipt of the notice.

- Under the third component, pharmacies are required, as well, to select a compliance officer who will manage and ensure compliance with HIPAA.

- As part of the fourth component of HIPAA, all employees working in the pharmacy environment in which PHI is maintained must receive training on the regulations within a reasonable time after being hired. This training necessarily includes pharmacists, technicians, and any other individuals who assist in the pharmacy.

- Finally, in some situations, it is necessary for the pharmacy to allow disclosure of PHI to a person or organization that is known under HIPAA as a "business associate." Typically, business associates perform a function that requires disclosure of PHI such as billing services, claims processing, utilization review, or data analysis. Under HIPAA, a pharmacy is allowed to disclose PHI to a business associate if the pharmacy obtains satisfactory assurances, usually in the form of a contract, that the business associate will use the information only for the purposes for which it was engaged by the pharmacy.

HIPAA also provides security provisions. These security provisions went into effect April 20, 2005, almost 2 years after the privacy provisions. The security standards are designed to protect the confidentiality of PHI that is threatened by the possibility of unauthorized access and interception during electronic transmission. Like the privacy provisions, any pharmacy that transmits any health information in electronic form is required to comply with the security rules.

In particular, the security standards define administrative, physical, and technical safeguards that the pharmacist must consider in order to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI.

A unique aspect of the security provisions is that they include both "required and addressable" implementation specifications. Required implementation specifications are those that must be met, whereas, in addressable specifications, the pharmacy must determine whether the suggested safeguards are reasonable and appropriate, given the size and capability of the organization as well as the risk.

While cost may be a factor that a covered entity may consider in determining whether to implement a particular specification, nonetheless a clear requirement exists that adequate security measures be implemented. Cost considerations are not meant to exempt covered entities from this responsibility.

Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997

The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA), enacted Nov. 21, 1997, amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act relating to the regulation of food, drugs, devices, and biological products. With the passage of FDAMA, Congress enhanced FDA's mission in ways that recognized the agency would be operating in a 21st century characterized by increasing technological, trade and public health complexities. FDAMA reauthorizes the Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992 and mandates the most wide-ranging reforms in agency practices since 1938. Provisions include measures to accelerate review of devices, regulate advertising of unapproved uses of approved drugs and devices, and regulate health claims for foods.

Prescription Drug User Fee

This authorizes the FDA to collect fees from companies that produce certain human drug and biological products. Any time a company wants the FDA to approve a new drug or biologic prior to marketing, it must submit an application along with a fee to support the review process. In addition, companies pay annual fees for each manufacturing establishment and for each prescription drug product marketed. Previously, taxpayers alone paid for product reviews through budgets provided by Congress. In the new program, industry provides the funding in exchange for FDA agreement to meet drug-review performance goals, which emphasize timeliness.

Off-Label Medication Uses

The law abolishes the long-standing prohibition on dissemination by manufacturers of information about unapproved uses of drugs and medical devices. The act allows a firm to disseminate peer-reviewed journal articles about an off-label indication of its product, provided the company commits itself to file, within a specified time frame, a supplemental application based on appropriate research to establish the safety and effectiveness of the unapproved use.

Pharmacy Compounding

The act creates a special exemption to ensure continued availability of compounded drug products prepared by pharmacists to provide patients with individualized therapies not available commercially. The law, however, seeks to prevent manufacturing under the guise of compounding by establishing parameters within which the practice is appropriate and lawful.

FDA Initiatives and Programs

The law enacts many FDA initiatives undertaken in recent years under Vice President Al Gore's Reinventing Government program. The codified initiatives include measures to modernize the regulation of biological products by bringing them in harmony with the regulations for drugs and eliminating the need for establishment license application; eliminate the batch certification and monograph requirements for insulin and antibiotics; streamline the approval processes for drug and biological manufacturing changes; and reduce the need for environmental assessment as part of a product application.

The act also codifies FDA's regulations and practice to increase patient access to experimental drugs and medical devices and to accelerate review of important new medications. In addition, the law provides for an expanded database on clinical trials which will be accessible by patients. With the sponsor's consent, the results of such clinical trials will be included in the database. Under a separate provision, patients will receive advance notice when a manufacturer plans to discontinue a drug on which they depend for life support or sustenance, or for a treatment of a serious or debilitating disease or condition.

2002 Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act

Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005

Medicaid Tamper-Resistant Prescription Law of 2007

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010

See also

References

- Pharmacy Times, A Review of Federal Legislation Affecting Pharmacy Practice, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200612-01.asp

- Strauss's Federal Drug Laws and Examination Review, Fifth Edition (revised), Steven Strauss, CRC Press, 2000

- Food and Drug Administration, Legislation, http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/default.htm

- Food and Drug Administration, History, http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/default.htm

- Wikipedia, Durham-Humphrey Amendment, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Durham-Humphrey_Amendment

- Wikipedia, Kefauver-Harris Amendment, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kefauver_Harris_Amendment

- Food and Drug Administration, The FDA's Drug Review Process: Ensuring Drugs Are Safe and Effective, http://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/ucm143534.htm

- Pharmacy Times, An Overview and Update of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200702-01.asp

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Title 21 United States Code (USC) Controlled Substances Act, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/21usc/index.html

- Controlled Substance Ordering System, http://www.deaecom.gov/

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Practitioner's Manual SECTION V – VALID PRESCRIPTION REQUIREMENTS, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/pract/section5.htm

- United States Department of Labor, OSH Act of 1970, http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owasrch.search_form?p_doc_type=OSHACT&p_toc_level=0&p_keyvalue=

- Wikipedia, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occupational_Safety_and_Health_Administration

- 16 CFR 1700.14, January 1, 2010, http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2010/janqtr/16cfr1700.14.htm

- The American Presidency Project, Gerald Ford: Statement on Signing the Medical Device Amendments of 1976, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=6069#axzz1JK6NwPDT

- CNN, Seven dead in Tylenol tampering scare -- October 1982, http://www.cnn.com/resources/video.almanac/1982/index2.html#tylenol

- TheScientist, The Orphan Drug Act Turns 25, Bob Grant, published 10/1/2008 ,volume 22 issue 10 page 67, http://www.the-scientist.com/templates/trackable/display/article1.jsp?type=article&o_url=article/display/55041&id=55041

- Authorized Generics: Good or Bad, Pharmacy Times, July 2006, http://www.pharmacytimes.com/issue/pharmacy/2006/2006-07/2006-07-5680

- Generic Epilepsy Drug Switch Tied to Seizures, WebMD, Dec. 6, 2004, http://www.webmd.com/epilepsy/news/20041206/generic-epilepsy-drug-switch-tied-to-seizures

- Dangerous Side Effects, Washington Post, July 16, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/15/AR2009071503378.html

- Estimated Dates of First Time Generics, Medco, Feb 5, 2010, http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CBsQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.medcohealth.com%2Fmedco%2Fcorporate%2Fhome.jsp%3FltSess%3Dy%26articleID%3DCorpAnticipatedFirstTimeGenericsPDF&ei=vABkTLXcOMP-8AbkleGwCg&usg=AFQjCNHJIuCKU5woVnGLG64tBTZNwNbLkg

- Generic News, Pharmacy Times, December 13, 2010, http://pharmacytimes.com/issue/pharmacy/2010/December2010/GenericNews-1210

- Orange Book Annual Preface, http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/ucm079068.htm

- Federal Nursing Home Reform Act from the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 or simply OBRA ‘87 SUMMARY, Hollis Turnham, Esquire, published by the National Long Term Care Ombudsman Resource Center, originally written January 2002, updated November 2007, http://www.allhealth.org/briefingmaterials/obra87summary-984.pdf

- Wikipedia, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omnibus_Budget_Reconciliation_Act_of_1987

- Pharmacy Technician Practice and Procedures, Gail G. Orum Alexander and James J. Mizner, Jr., McGraw Hill, 2011