Drug Enforcement Administration

From Rx-wiki

The DEA was created by President Richard Nixon through an Executive Order in July 1973 in order to establish a single unified command to combat "an all-out global war on the drug menace." At its outset, the DEA had 1,470 Special Agents and a budget of less than $75 million. Furthermore, in 1974, the DEA had 43 foreign offices in 31 countries. Today, the DEA has approximately 5,000 Special Agents, a budget of more than $2 billion and 86 foreign offices in 62 countries.

Contents

Mission Statement

The mission of the DEA is to enforce the controlled substances laws and regulations of the United States and bring to the criminal and civil justice system of the United States, or any other competent jurisdiction, those organizations and principal members of organizations, involved in the growing, manufacture, or distribution of controlled substances appearing in or destined for illicit traffic in the United States; and to recommend and support non-enforcement programs aimed at reducing the availability of illicit controlled substances on the domestic and international markets.

In carrying out its mission as the agency responsible for enforcing the controlled substances laws and regulations of the United States, the DEA's primary responsibilities include:

- Investigation and preparation for the prosecution of major violators of controlled substance laws operating at interstate and international levels.

- Investigation and preparation for prosecution of criminals and drug gangs who perpetrate violence in our communities and terrorize citizens through fear and intimidation.

- Management of a national drug intelligence program in cooperation with federal, state, local, and foreign officials to collect, analyze, and disseminate strategic and operational drug intelligence information.

- Seizure and forfeiture of assets derived from, traceable to, or intended to be used for illicit drug trafficking.

- Enforcement of the provisions of the Controlled Substances Act as they pertain to the manufacture, distribution, and dispensing of legally produced controlled substances.

- Coordination and cooperation with federal, state and local law enforcement officials on mutual drug enforcement efforts and enhancement of such efforts through exploitation of potential interstate and international investigations beyond local or limited federal jurisdictions and resources.

- Coordination and cooperation with federal, state, and local agencies, and with foreign governments, in programs designed to reduce the availability of illicit abuse-type drugs on the United States market through nonenforcement methods such as crop eradication, crop substitution, and training of foreign officials.

- Responsibility, under the policy guidance of the Secretary of State and U.S. Ambassadors, for all programs associated with drug law enforcement counterparts in foreign countries.

- Liaison with the United Nations, Interpol, and other organizations on matters relating to international drug control programs.

Genealogy

Medication Schedules

Controlled substances are medications with further restrictions due to abuse potential. There are 5 schedules of controlled substances with various prescribing guidelines based on abuse potential counter balanced by potential medicinal benefit as determined by the Drug Enforcement Administration and individual state legislative branches. The DEA is provided with this authority by the Controlled Substances Act. Below is a brief explanation of the schedules along with example medications.

Schedule I (CI)

- Characteristics:

- Unaccepted medical use.

- Highest potential for abuse.

- Not available by a prescription.

- Examples:

- LSD

- heroin

- Quaaludes (methaqualone)

Schedule II (CII)

- Characteristics:

- High potential for abuse or misuse.

- Sufficient medicinal use to justify availability as a prescription.

- Examples:

- oxycodone

- morphine

- amphetamines

Schedule III (CIII)

- Characteristics:

- Potential risk for abuse, misuse, and dependence.

- Examples:

- Vicodin (hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen)

- Codeine and codeine containing products in a solid dosage form (tablet, capsule, etc.).

Schedule IV (CIV)

- Characteristics:

- Low potential for abuse and limited risk of dependence.

- Examples:

- phenobarbital

- benzodiazepines

- other sedatives and hypnotics

Schedule V (CV)

- Characteristics:

- Low potential for abuse or misuse.

- Examples:

- Cough medicines that contain a limited amount of codeine.

- Antidiarrheal medications that contain a limited amount of an opiate such as Lomotil (diphenoxylate and atropine).

CI medications are not available via a prescription

CII medications may be written for a maximum 90 day supply without refills

CIII – CV medications may be written for up to a 6 month supply

Many problems associated with drug abuse are the result of legitimately-manufactured controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into the illicit drug traffic. Many of the narcotics, depressants and stimulants manufactured for legitimate medical use are subject to abuse, and have therefore been brought under legal control. The goal of controls is to ensure that these "controlled substances" are readily available for medical use, while preventing their distribution for illicit sale and abuse.

Prescription drug abuse facts

- Nearly 7 million Americans were abusing prescription drugs in 2006—more than the number who are abusing cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, Ecstasy, and inhalants, combined. That 7 million was just 3.8 million in 2000, an 80 percent increase in just 6 years.

- Prescription pain relievers are new drug users’ drug of choice, vs. marijuana or cocaine.

- Opioid painkillers now cause more drug overdose deaths than cocaine and heroin combined.

- 1 in 7 teens admit to abusing prescription drugs to get high in the past year. Sixty percent of teens who abused prescription pain relievers did so before the age of 15.

- 2 in 5 teens believe that prescription drugs are “much safer” than illegal drugs. And 3 in 10 teens believe that prescription pain relievers are not addictive.

- Misuse of painkillers represents three-fourths of the overall problem of prescription drug abuse; hydrocodone is the most commonly diverted and abused controlled pharmaceutical in the U.S.

- Twenty-five percent of drug-related emergency department visits are associated with abuse of prescription drugs.

- Methods of acquiring prescription drugs for abuse include “doctor-shopping,” traditional drug-dealing, theft from pharmacies or homes, illicitly acquiring prescription drugs via the Internet, and from friends or relatives.

- DEA works closely with the medical community to help them recognize drug abuse and signs of diversion and relies on their input and due diligence to combat diversion. Doctor involvement in illegal drug activity is rare—less than one tenth of one percent of more than 750,000 doctors are the subject of DEA investigations each year—but egregious drug violations by practitioners unfortunately do sometimes occur. DEA pursues criminal action against such practitioners.

- DEA Internet drug trafficking initiatives over the past several years have identified and dismantled organizations based both in the U.S. and overseas, and arrested dozens of conspirators. As a result of major investigations such as Operations Web Tryp, PharmNet, Cyber Rx, Cyber Chase, and Click 4 Drugs, Bay Watch, and Lightning Strike, tens of millions of dosage units of prescription drugs and tens of millions of dollars in assets have been seized.

Diversion control system

Many problems associated with drug abuse are the result of legitimately-manufactured controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into the illicit drug traffic. Many of the narcotics, depressants and stimulants manufactured for legitimate medical use are subject to abuse, and have therefore been brought under legal control. The goal of controls is to ensure that these "controlled substances" are readily available for medical use, while preventing their distribution for illicit sale and abuse.

Under federal law, all businesses which manufacture or distribute controlled drugs, all health professionals entitled to dispense, administer or prescribe them, and all pharmacies entitled to fill prescriptions must register with the DEA. Authorized registrants receive a "DEA number". Registrants must comply with a series of regulatory requirements relating to drug security, records accountability, and adherence to standards.

A DEA number is a series of numbers assigned to a health care provider (such as a dentist, physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) allowing them to write prescriptions for controlled substances. Legally the DEA number is solely to be used for tracking controlled substances. The DEA number, however, is often used by the industry as a general "prescriber" number that is a unique identifier for anyone who can prescribe medication.

- 2 letters and 7 digits

- The first letter is always an A (deprecated), B (most common), or F (new) for a dispenser. (Also M is available for mid-level practitioners in some states and either P or R is used for a wholesaler)

- The second letter is typically the initial of the registrant's last name

- The seventh digit is a "checksum" that is calculated as:

- Add together the first, third and fifth digits

- Add together the second, fourth and sixth digits and multiply the sum by 2

- Add the above 2 numbers

- The last digit (the ones value) of this last sum is used as the seventh digit in the DEA number

Purchasing

Controlled substances require special consideration when it comes to purchasing.

Schedule III – V drugs may be ordered by a pharmacy or other appropriate dispensary on a general order from a wholesaler and you should check the delivery in against the original order.

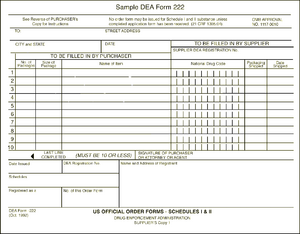

The DEA form 222 is a triplicate form. The pharmacy retains the third sheet while sending the first and second pages to the wholesaler. The wholesaler is responsible for sending the second page to the DEA while retaining the first page for its own records. When the Schedule II medications arrive in the pharmacy they should be checked in against the DEA form.

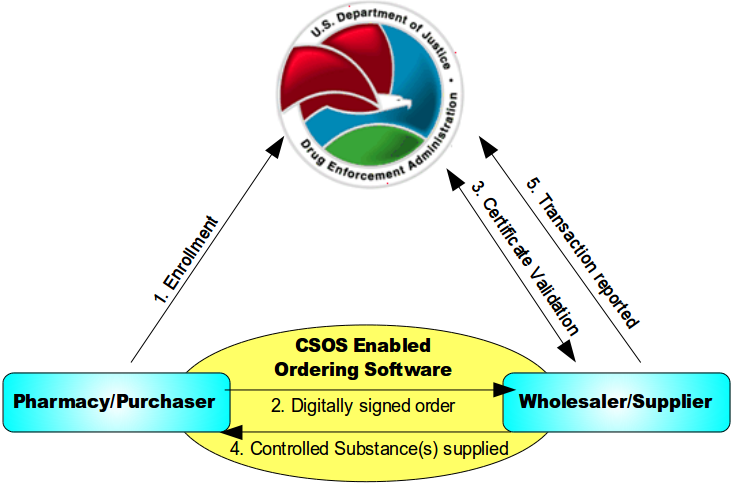

Below is an image explaining how ordering schedule II medications work with a controlled substances ordering system (CSOS)

- An individual enrolls with the DEA and, once approved, is issued a personal CSOS Certificate.

- The purchaser creates an electronic 222 order using an approved ordering software. The order is digitally signed using the purchaser's personal CSOS Certificate and then transmitted to the suppliers. The paper 222 is not required for electronic ordering.

- The supplier receives the purchase order and verifies that the purchaser's certificate is valid with the DEA. Additionally, the supplier validates the electronic order information just like it would a paper order.

- The supplier completes the order and ships to the purchaser. Any communications regarding the order are sent electronically.

- The order is reported by the supplier to the DEA within two business days.

Receiving

When the pharmacy receives controlled substances they should be carefully checked in against the purchase order including product name, quantity, strength, and package size. Controlled substances are shipped in separate containers from the rest of the pharmacy order and should be checked in by a pharmacist, although pharmacy technicians may assist with this process under the direct supervision of a pharmacist. Schedule II medications need to be checked in against your DEA 222 form (whether the paper triplicate form, or the electronic form on your CSOS enabled software).

Schedule II medications may be stocked separately in a secure place or disbursed throughout the stock. Their stock must be continually monitored and documented.

You may store CIII – CV medications in one of two ways:

- In a secured vault or,

- Dispersed throughout the pharmacy stock. By dispersing the stock through out, you effectively prevent someone from being able to obtain all your controlled substances since they can not do easy "One stop shopping."

Theft or loss of controlled substances

In the event that controlled substances are stolen, or are found to be missing a pharmacy should:

- contact the local police and the DEA,

- fill out and file DEA form 106.

The DEA form 106 is available as both a printed form, or may be filed electronically. To obtain the printed form click here and printout the PDF. To file elctronically proceed to https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/webforms/dtlLogin.jsp .

The DEA requires that theft of controlled substances must be reported within 24 hours.

Anabolic steroids

The Anabolic Steroids Control Act (ASCA) of 1990 gave the DEA authority over anabolic steriods. Anabolic steroids are defined as synthetic derivatives of the male hormone testosterone, having pronounced anabolic properties and relatively weak andronergic properties (i.e., producing masculine characteristics), which are used clinically mainly to promote growth and to repair body tissue in senility, debilitating illness, and convalescence. Anabolic steroids may also be referred to as andronergic-anabolic steroids.

The DEA has classified anabolic steroids as Schedule III controlled substances; however, certain products which are considered to have no significant potential for abuse because of their concentration, preparation, mixture, or delivery system, are exempt from being classified as control substances (such as Premarin with methyltestosterone tablets).

In addition, the classification does not include anabolic steroids expressly intended for cattle or other non-human species and which are approved by the FDA. However, prescribing, dispensing or distributing such substances for other than implantation in cattle or other non-human species is a violation of the law.

Drug addiction treatment

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) permits physicians who meet certain qualifications to treat opioid addiction with Schedule III, IV, and V narcotic medications that have been specifically approved by the Food and Drug Administration for that indication. Such medications may be prescribed and dispensed by waived physicians in treatment settings other than the traditional Opioid Treatment Program (methadone clinic) setting.

Since there is only one narcotic medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of opioid addiction within the Schedules given, DATA 2000 basically refers to the use of buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid addiction. Methadone is a Schedule II narcotic approved for the same purpose within the highly regulated methadone clinic setting.

Under the Act, physicians may apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid addiction or dependence. Requirements include a current State medical license, a valid DEA registration number, specialty or subspecialty certification in addiction from the American Board of Medical Specialties, American Society of Addiction Medicine, or American Osteopathic Association. Exceptions were also created for physicians who participated in the initial studies of buprenorphine and for State certification of addiction specialists. However, the Act is intended to bring the treatment of addiction back to the primary care provider. Thus most waivers are obtained after taking an 8 hour course from one of the five medical organizations designated in the Act and otherwise approved by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. When a physician qualifies for the waiver, he is given a second DEA number that begins with an 'X'. This new DEA number is only to be used when prescribing buprenorphine for the purpose of treating addictions. Once a physician obtains the waiver, he or she may treat up to 30 patients for narcotic addiction with buprenorphine. Recent changes to DATA 2000 have increased the patient limit to 100 for physicians that have had their waiver for a year or more and request the higher limit in writing.

Methamphetamines

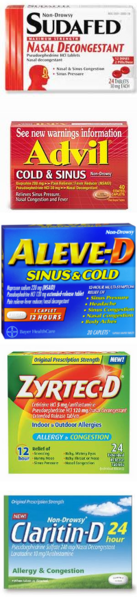

Ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine are precursor chemicals used in the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine or amphetamine. They are also common ingredients used to make cough, cold, and allergy products. Passage of the CMEA was accomplished to curtail the clandestine production of methamphetamine. States that have enacted similar or more restrictive retail regulations have seen a dramatic drop in small clandestine labs.

The Federal statute included the following requirements for merchants who sell these products:

- A retrievable record of all purchases identifying the name and address of each party to be kept for two years.

- Required verification of proof of identity of all purchasers

- Required protection and disclosure methods in the collection of personal information

- Reports to the Attorney General of any suspicious payments or disappearances of the regulated products

- Non-liquid dose form of regulated product may only be sold in unit dose blister packs

- Regulated products are to be sold behind the counter or in a locked cabinet in such a way as to restrict access

- Daily sales of regulated products not to exceed 3.6 grams without regard to the number of transactions

- A 30-day sales limit not to exceed 9 grams of pseudoephedrine base in regulated products

- The law gives similar regulations to mail order purchases, except the monthly sales limit is only 7.5 grams.

The DEA does report a decrease in clandestine methamphetamine labs since the passage of the CMEA.

Conclusion

The Drug Enforcement Administration works closely not only with other law enforcement entities such as the FBI, Interpol, and local authorities but also the medical industry including physicians, drug manufacturers, and pharmacies to regulate both highly abusable street drugs along with medications that have great potential for patient benefit but also have considerable abuse potential. While the landscape in which the DEA operates has changed significantly in the past 40 years there task remains the same as when they were conceived, to combat drug abuse.

See also

Federal pharmacy law

Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act

Anabolic Steroids Control Act

Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act

Food and Drug Administration

References

- DEA, DEA History, http://www.justice.gov/dea/history.htm

- DEA, DEA Staffing and Budget, http://www.justice.gov/dea/agency/staffing.htm

- DEA, DEA Mission Statement, http://www.justice.gov/dea/agency/mission.htm

- DEA, Genealogy, http://www.justice.gov/dea/agency/genealogy.htm

- DEA, Fact Sheet: Prescription Drug Abuse - A DEA Focus, http://www.justice.gov/dea/concern/prescription_drug_fact_sheet.html

- Drug Trends, presented by DEA special agent Mike Kupchik, September 7,2011

- Pharmacy Times, A Review of Federal Legislation Affecting Pharmacy Practice, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200612-01.asp

- Strauss's Federal Drug Laws and Examination Review, Fifth Edition (revised), Steven Strauss, CRC Press, 2000

- Pharmacy Times, An Overview and Update of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200702-01.asp

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Title 21 United States Code (USC) Controlled Substances Act, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/21usc/index.html

- Controlled Substance Ordering System, http://www.deaecom.gov/

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Practitioner's Manual SECTION V – VALID PRESCRIPTION REQUIREMENTS, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/pract/section5.htm

- "Steroids", http://students.cis.uab.edu/archived/zmabeus/long-term.html

- Wikipedia, Drug Addiction Treatment Act, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Addiction_Treatment_Act

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act 2005, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/meth/index.html

- Wikipedia, Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act 2005, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combat_Methamphetamine_Epidemic_Act_of_2005