Pharmacy laws and regulations

From Rx-wiki

The pharmaceutical industry is a highly regulated industry with federal laws impacting it dating back as far as the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 to the Kefauver-Harris Amendment of 1962 to various effects from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, and many laws in between. Despite being a highly regulated industry already, according a recent (2010) Harris Poll, 10% of Americans would like to see an increase in regulation on pharma and drug companies. With that in mind, there are sure to be additional regulations placed on the industry in the future.

This article will focus on the following knowledge areas to provide an overview of pharmacy laws and regulations:

- Storage, handling, and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes (e.g., MSDS)

- Hazardous substances exposure, prevention and treatment (e.g., eye wash, spill kit, MSDS)

- Controlled substance transfer regulations (DEA)

- Controlled substance documentation requirements for receiving, ordering, returning, loss/theft, destruction (DEA)

- Formula to verify the validity of a prescriber’s DEA number (DEA)

- Record keeping, documentation, and record retention (e.g., length of time prescriptions are maintained on file)

- Restricted drug programs and related prescription-processing requirements (e.g., thalidomide, isotretinoin, clozapine)

- Professional standards related to data integrity, security, and confidentiality (e.g., HIPAA, backing up and archiving)

- Requirement for consultation (e.g., OBRA-90)

- FDA’s recall classification

- Infection control standards (e.g., laminar air flow, clean room, hand washing, cleaning counting trays, countertop, and equipment) (OSHA, USP 795 and 797)

- Record keeping for repackaged and recalled products and supplies (TJC, BOP)

- Professional standards regarding the roles and responsibilities of pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and other pharmacy employees (TJC, BOP)

- Reconciliation between state and federal laws and regulations

- Facility, equipment, and supply requirements (e.g., space requirements, prescription file storage, cleanliness, reference materials) (TJC, USP, BOP)

Contents

- 1 Terminology

- 2 Safety requirements

- 3 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (with updates)

- 4 Restricted drug programs

- 5 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990

- 6 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- 7 Drug recalls

- 7.1 What is a drug recall?

- 7.2 Recall classifications

- 7.3 How drug recalls work

- 7.4 10 worst drug recalls in the United States

- 7.4.1 Fen-Phen (fenfluramine and phentermine)

- 7.4.2 Diethylstilbestrol (a.k.a., DES)

- 7.4.3 Baycol (cerivastatin)

- 7.4.4 Vioxx (rofecoxib)

- 7.4.5 Bextra (valdecoxib)

- 7.4.6 Rezulin (troglitazone)

- 7.4.7 Able Laboratories generic prescription medications

- 7.4.8 Seldane (terfenadine)

- 7.4.9 Phenylpropanolamine (a.k.a., PPA)

- 7.4.10 Posicor (mibefradil)

- 8 Infection control standards

- 9 Professional standards in pharmacy

- 10 Facility, equipment, and supply requirements

- 11 See also

- 12 References

Terminology

To get started with, there is some terminology that should be defined.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) - NIOSH is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). NIOSH is responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. Of particular interest to pharmacy is their role in establishing a list of Hazardous Drugs (HDs).

hazardous drugs (HDs) - Hazardous drugs are identified as hazardous or potentially hazardous based on the following six criteria:

- carcinogenicity, which is the ability to cause cancer in animal models, humans or both;

- teratogenicity, which is the ability to cause defects on fetal development or fetal malformation;

- drugs are known to have the potential to cause fertility impairment;

- organ toxicity at low doses in humans or animals;

- genotoxicity, which is the ability to cause a change or mutation in genetic material; and

- new drugs that mimic existing HDs in structure or toxicity.

These drugs are often classified as antineoplastics, cytotoxic agents, biologic agents, antiviral agents, and/or immunosuppressive agents. As of writing this text the 2014 NIOSH list of HDs is the current standard and may be found at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2014-138/pdfs/2014-138.pdf

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) - OSHA is a government agency within the United States Department of Labor responsible for maintaining safe and healthy work environments.

Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) - OSHA-required notices on hazardous substances which provide information on potential hazards associated with a particular material or product, safe handling procedures, proper clean-up, and first aid information.

personal protective equipment (PPE) - Personal protective equipment is worn by an individual to provide both protection to the wearer from the environment or specific items they are manipulating, and to prevent exposing the environment or the items being manipulated directly to the wearer of the PPE.

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) - The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is a United States Department of Justice law enforcement agency, a federal police service tasked with enforcing the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

controlled substances - Controlled substances are medications with restrictions due to abuse potential. There are 5 schedules of controlled substances with various prescribing guidelines based on abuse potential, counter balanced by potential medicinal benefit as determined by the Drug Enforcement Administration and individual state legislative branches.

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) - The Food and Drug Administration may require risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) on medications, if necessary, to minimize the risks associated with some drugs. REMS may require a medication guide, a communications plan, elements to assure safe use, an implementation plan, and a timetable for submission of assessments.

United States Pharmacopeia (USP) - The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) is the official pharmacopeia of the United States, and is published dually with the National Formulary as the USP-NF. Prescriptions and over-the-counter medicines, and other healthcare products sold in the United States, are required to follow the standards in the USP-NF. The USP also sets standards for food ingredients and dietary supplements. Chapters in the USP that are listed as below 1000 are considered enforceable, while chapters enumerated as 1000 or greater are considered guidelines. Therefore, USP 797 and USP 795 are considered enforceable, while USP 1160 and USP 1176 are simply considered guidelines for best practices.

compounded sterile preparations (CSP) - Compounded sterile preparations are admixtures that need to be assembled under aseptic conditions to prevent contamination.

Safety requirements

There is a vast array of information to be aware of with safety requirements posed by various organizations. Of particular concern is the safe storage, handling, managing accidental exposure, and disposal of hazardous materials. Hazardous drugs are drugs that are known to cause genotoxicity, which is the ability to cause a change or mutation in genetic material; carcinogenicity, which is the ability to cause cancer in animal models, humans or both; teratogenicity, which is the ability to cause defects on fetal development or fetal malformation; and lastly, hazardous drugs are known to have the potential to cause fertility impairment, which is a major concern for most clinicians. These drugs can be classified as antineoplastics, cytotoxic agents, biologic agents, antiviral agents, and immunosuppressive agents. This is why safe handling of hazardous drugs is crucial.

Product storage

The safety requirements include everything from the proper inventory rotation to avoid dispensing expired products, to material safety data sheets to provide the necessary information for safe clean up after accidental spills, to appropriate handling of oncology materials, and proper storage of chemicals and flammable items.

Proper rotation of inventory and periodic checking of expirations help to reduce the potential for dispensing expired medications. It also maximizes the utilization of inventory before medications become outdated. When looking at expirations on medication vials, it is important to note that if a medication only mentions the month and year, but not the day, then you are to treat it as expiring at the end of the month. As an example, if a medication is marked as expiring on 02/2020, then you would treat it as expiring on February 29, 2020.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires all workplaces, including pharmacies, to carry material safety data sheets (MSDS) for all hazardous substances that are stored on the premises. This includes oncology drugs and volatile chemicals along with other hazardous chemicals. The MSDS provide handling, clean-up, and first-aid information.

Segregating inventory by drug categories helps to prevent potentially harmful errors. The Joint Commission (TJC), formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), requires that internal and external medications must be stored separately. This reduces the potential that someone will dispense or administer an external product for internal use. The Joint Commission also has requirements for separate storage of oncology drugs and volatile or flammable substances.

Hazardous drugs (e.g., oncology drugs) shall have a separate space on the shelves at or below eye level and should be labeled in such a way that it will alert staff of the hazardous potential of these medications. HDs in their final dosage form or unit of use may be interspersed with other medications on the shelves but still need to be adequately labeled. Oncology drugs are often cytotoxic themselves and must be handled with extreme care. They should be received in a sealed protective outer bag that restricts dissemination of the drug if the container leaks or is broken. Staff should wear personal protective equipment (PPE) when receiving and storing HDs. When an increased potential exists for exposure to hazardous drugs, all personnel involved must wear additional PPE while following a hazardous materials cleanup procedure. All exposed materials must be properly disposed of in hazardous waste containers.

Volatile or flammable substances (including tax free alcohol) require careful storage. They must have a cool location that is properly ventilated. Their storage area must be designed to reduce fire and explosion potential.

Product handling

Whenever receiving and/or handling hazardous materials, individuals are recommended to use personal protective equipment (PPE). PPE typically consists of booties, hair covers, a respirator (typically a HEPA mask), face shield, coated gowns capable of providing at least 4 hours of protection if accidentally exposed, powder free impermeable gloves (double glove using ASTM-tested chemotherapy gloves). The American Society of Healthsystem Pharmacists (ASHP) and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) both recommend changing gowns every three hours during extended work with hazardous substances. It is also recommended that gloves be changed every 30 minutes. For more specific guidelines associated with the proper selection of PPE for use with HDs, consult the following table (table has been adopted from material in the USP):

| PPE articles for use with HDs | Specific description/definition of PPE and its usage |

| head, hair, and shoe covers |

Head and hair (including beard and moustache, if applicable) and shoe covers shall be worn to reduce the possibility of particulate or microbial contamination in HD compounding areas. Hair, head, and shoe covers provide additional protection from contact with HD residue on surfaces and floors. Do not wear shoe covers outside the HD compounding areas to avoid spreading drug contamination to other areas and possibly exposing unprotected workers. |

| eye and face protection | Appropriate eye and face protection shall be worn when handling HDs outside an engineering control. A full-facepiece respirator also provides eye and face protection. Goggles shall be used when eye protection is needed; eye glasses alone or safety glasses with side shields do not provide adequate protection to the eyes from splashes.

Many HDs are irritating to eyes and mucous membranes. Follow these work practices when using eye and face protection:

|

| respirator | For most activities requiring respiratory protection, an NIOSH-certified N95 or more protective respirator is sufficient to protect against airborne particles; however, these respirators offer no protection against gases and vapors and little protection against direct liquid splashes (see CDC’s Respirator Trusted-Source Information at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/disp_part/RespSource3healthcare.html#e). Surgical masks do not provide respiratory protection from drug exposure and should not be used to compound or administer drugs. A surgical N95 respirator provides the respiratory protection of an N95 respirator and the splash protection provided by a surgical mask. |

| gowns | Disposable gowns that protect the worker from spills and splashes of HDs and waste materials and that have been tested to resist permeability by HDs shall be worn when handling HDs. Selection of gowns shall be based on the HDs used.

Disposable gowns made of polyethylene-coated polypropylene or other laminate materials offer better protection than those of noncoated materials. Gowns shall close in the back (no open front), have long sleeves, and have closed cuffs that are elastic or knit. Gowns shall not have seams or closures that could allow drugs to pass through. Cloth laboratory coats, surgical scrubs, isolation gowns, or other absorbent materials are not appropriate outer wear when handling HDs, because they permit the permeation of HDs and can hold spilled drugs against the skin and increase exposure. |

| gloves | Gloves used shall be labeled as ASTM-tested chemotherapy gloves; this information is available on the box or from the manufacturer.

|

Accidental exposure

Workers may be exposed to a hazardous drug at any point during its manufacture, transport, distribution, receipt, storage, preparation, and administration, as well as during waste handling, and equipment maintenance and repair. All workers involved in these activities have the potential for contact with uncontained drug.

In case of accidental exposure, you should consult the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) which provide information on potential hazards associated with a particular material or product, safe handling procedures, proper clean-up, and first aid information. An eyewash is an appropriate device to utilize if hazardous or other unwanted materials come in contact with the eye. The individual exposed will probably be required to file an initial incident report (IIR) with their facility.

Facilities that utilize hazardous drugs are required to have spill kits, which may be useful in the containment and cleanup of hazardous materials. Spill kits typically contain PPE, waste containers, warning signs to help minimize traffic through the contaminated area, powders for solidifying liquids, disposable scoops and brushes, absorbent gauze or pads, and a common deactivating agent such as sodium hypochlorite.

Proper waste disposal

Properly labeled, leak-proof, and spill-proof containers of non reactive plastic are required for areas where hazardous waste is generated, and can be further broken down into either yellow or black containers. Fully used vials, syringes, tubing, and bags of hazardous drug waste, along with PPE used while working with hazardous drugs, may be disposed in yellow, properly labeled containers. Also, any partially used or expired hazardous drugs that are not also considered to be RCRA (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act) regulated hazardous drugs should be placed in these yellow buckets. Trace contaminated items such as booties, gowns, and masks, even if they were not involved in spills, MUST be treated as hazardous waste (the yellow buckets are sufficient for this).

Partially used bags, vials, syringes, etc. of RCRA listed hazardous pharmaceutical waste MUST be placed in black RCRA approved containers. Hazardous waste must be properly manifested and transported by a federally permitted hazardous waste transporter to a federally permitted hazardous waste storage, treatment, or disposal facility.

A licensed contractor may be hired to manage the hazardous waste program.

Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (with updates)

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was passed by Congress as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. And signed into law by President Richard Nixon on October 27, 1970.

Since the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act in 1914 many attempts had been made to strengthen government control and regulation of illicit substances with varying degrees of success. The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act is our countries most ambitious attempt to date and replaces similar legislation from the past including the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act.

The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act provides for the classification, acquisition, distribution, registration/verification of prescribers, and appropriate record keeping requirements of controlled substances. This act also provided the legal framework for the creation of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which is the organization primarily tasked with the enforcement responsibilities of the CSA.

To ensure an appropriate understanding of this law various updates will be included with discussion of this act.

Classification of controlled substances

Besides over the counter medications (OTC) such as aspirin and ibuprofen, behind the counter medications (BTC) such as Allegra-D (fexofenadine with pseudoephedrine), and prescription medications (Rx legend) such as amoxicillin and digoxin, there is another group of medications to be concerned with called controlled substances.

Controlled substances are medications with further restrictions due to abuse potential. There are 5 schedules of controlled substances with various prescribing guidelines based on abuse potential counter balanced by potential medicinal benefit as determined by the Drug Enforcement Administration and individual state legislative branches. The DEA is provided with this authority by the Controlled Substances Act. Below is a brief explanation of the schedules along with example medications.

Schedule I (CI)

- Characteristics:

- Unaccepted medical use.

- Highest potential for abuse.

- Not available by a prescription.

- Examples:

- LSD

- heroin

- Quaaludes (methaqualone)

Schedule II (CII)

- Characteristics:

- High potential for abuse or misuse.

- Sufficient medicinal use to justify availability as a prescription.

- Examples:

- oxycodone

- morphine

- amphetamines

- Vicodin (hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen)

Schedule III (CIII)

- Characteristics:

- Potential risk for abuse, misuse, and dependence.

- Examples:

- Suboxone (buprenorphine and naloxone)

- AndroGel (testosterone)

- Codeine when combined with acetaminophen or a cough suppressant in a solid dosage form (tablet, capsule, etc.).

Schedule IV (CIV)

- Characteristics:

- Low potential for abuse and limited risk of dependence.

- Examples:

- phenobarbital

- benzodiazepines

- other sedatives and hypnotics

Schedule V (CV)

- Characteristics:

- Low potential for abuse or misuse.

- Examples:

- Cough medicines that contain a limited amount of codeine.

- Antidiarrheal medications that contain a limited amount of an opiate such as Lomotil (diphenoxylate and atropine).

Many problems associated with drug abuse are the result of legitimately-manufactured controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into the illicit drug traffic. Many of the narcotics, depressants and stimulants manufactured for legitimate medical use are subject to abuse, and have therefore been brought under legal control. The goal of controls is to ensure that these "controlled substances" are readily available for medical use, while preventing their distribution for illicit sale and abuse.

Purchasing

Controlled substances require special consideration when it comes to purchasing.

Schedule III – V drugs may be ordered by a pharmacy or other appropriate dispensary on a general order from a wholesaler and you should check the delivery in against the original order.

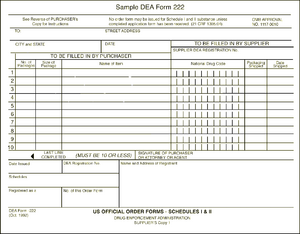

The DEA form 222 is a triplicate form. The pharmacy retains the third sheet while sending the first and second pages to the wholesaler. The wholesaler is responsible for sending the second page to the DEA while retaining the first page for its own records. When the Schedule II medications arrive in the pharmacy they should be checked in against the DEA form.

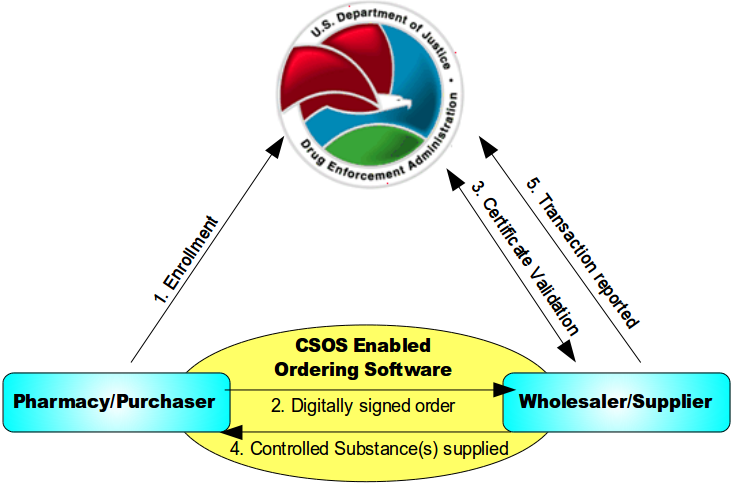

Below is an image explaining how ordering schedule II medications work with a controlled substances ordering system (CSOS)

- An individual enrolls with the DEA and, once approved, is issued a personal CSOS Certificate.

- The purchaser creates an electronic 222 order using an approved ordering software. The order is digitally signed using the purchaser's personal CSOS Certificate and then transmitted to the suppliers. The paper 222 is not required for electronic ordering.

- The supplier receives the purchase order and verifies that the purchaser's certificate is valid with the DEA. Additionally, the supplier validates the electronic order information just like it would a paper order.

- The supplier completes the order and ships to the purchaser. Any communications regarding the order are sent electronically.

- The order is reported by the supplier to the DEA within two business days.

Receiving

When the pharmacy receives controlled substances they should be carefully checked in against the purchase order including product name, quantity, strength, and package size. Controlled substances are shipped in separate containers from the rest of the pharmacy order and should be checked in by a pharmacist, although pharmacy technicians may assist with this process under the direct supervision of a pharmacist. Schedule II medications need to be checked in against your DEA 222 form (whether the paper triplicate form, or the electronic form on your CSOS enabled software).

Schedule II medications may be stocked separately in a secure place or disbursed throughout the stock. Their stock must be continually monitored and documented.

You may store CIII – CV medications in one of two ways:

- In a secured vault or,

- Dispersed throughout the pharmacy stock. By dispersing the stock through out, you effectively prevent someone from being able to obtain all your controlled substances since they can not do easy "One stop shopping."

Controlled substances prescriptions

Controlled substances have some additional things to keep in mind when reviewing prescription orders. All controlled substance prescriptions require the prescriber to include their DEA number on the prescription. While traditional prescriptions are good for one year from the date they are written and (at the prescriber's discretion) may have a sufficient number of refills to cover an entire one year supply; controlled substances have some differences based on which schedule they are. Schedule V medications may be refilled for up to a one year supply like prescriptions for non-controlled substances. Schedule III-IV medications may be written for up to a six month supply of medications including any refills on the original prescription. Schedule II medications may be written for up to a 90 day supply but may not include any refills. If a patient has a 30 day limit from their insurance the physician would need to write three separate prescriptions for thirty days to cover the full 90 days. Prescribers are not allowed to exceed a 90 day supply of a schedule II medications with out seeing the patient again.

Telephone orders and facsimiles

Pharmacies may accept telephone orders and faxes for schedule III-V medications. The pharmacist must immediatley reduce telephone order prescriptions to writing. Schedule II medications may not be ordered over the phone or via a fax machine under ordinary circumstances.

DEA has granted three exceptions to the facsimile prescription requirements for Schedule II controlled substances. The facsimile of a Schedule II prescription may serve as the original prescription as follows:

- A practitioner prescribing Schedule II narcotic controlled substances to be compounded for the direct administration to a patient by parenteral, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous or intraspinal infusion may transmit the prescription by facsimile. The pharmacy will consider the facsimile prescription a "written prescription" andno further prescription verification is required.All normal requirements of a legal prescription must be followed.

- Practitioners prescribing Schedule II controlled substances for residents of Long Term Care Facilities (LTCF) may transmit a prescription by facsimile to the dispensing pharmacy. The practitioner’s agent may also transmit the prescription to the pharmacy. The facsimile prescription serves as the original written prescription for the pharmacy.

- A practitioner prescribing a Schedule II narcotic controlled substance for a patient enrolled in a hospice care program certified and/or paid for by Medicare under Title XVIII or a hospice program which is licensed by the state may transmit a prescription to the dispensing pharmacy by facsimile. The practitioner or the practitioner’s agent may transmit the prescription to the pharmacy. The practitioner or agent will note on the prescription that it is for a hospice patient. The facsimile serves as the original written prescription.

For Schedule II controlled substances, an oral order is only permitted in an emergency situation. An emergency situation is defined as a situation in which:

- Immediate administration of the controlled substance is necessary for the proper treatment of the patient.

- No appropriate alternative treatment is available.

- Provision of a written prescription to the pharmacist prior to dispensing is not reasonably possible for the prescribing physician.

In an emergency, a practitioner may call-in a prescription for a Schedule II controlled substance by telephone to the pharmacy, and the pharmacist may dispense the prescription provided that the quantity prescribed and dispensed is limited to the amount adequate to treat the patient during the emergency period. The prescribing practitioner must provide a written and signed prescription to the pharmacist within seven days. Further, the pharmacist must notify DEA if the prescription is not received.

E-prescribing

The regulations concerning electronic transmission of controlled substances via e-prescribing recently changed. As of June 1, 2010 physicians and pharmacies are now allowed to transmit prescriptions for Schedule II, III, IV, and V medications as long as they are using properly certified software (i.e., SureScripts). While this is a recent shift in federal law, some states may still prohibit e-prescribing for controlled substances.

Partial fill of prescriptions

Pharmacists often question the DEA rule regarding the partial refilling of Schedule III, IV, or V prescriptions. Confusion lies in whether or not a partial fill or refill is considered one fill or refill, or if the prescription can be dispensed any number of times until the total quantity prescribed is met or 6 months has passed. According to the DEA's interpretation, as long as the total quantity dispensed meets with the total quantity prescribed with the refills, and they are dispensed within the 6-month period, the number of refills is irrelevant.

The Code of Federal Regulations states that the partial filling of a prescription for a controlled substance listed in Schedule III, IV, or V is permissible, provided that:

- Each partial filling is recorded in the same manner as a refilling.

- The total quantity dispensed in all partial fillings does not exceed the total quantity prescribed.

- No dispensing occurs 6 months after the date on which the prescription was issued for schedule III and IV medications or 12 months after the date on which the prescription was issued for schedule V medications.

For a Schedule II drug, the pharmacist may partially dispense a prescription if he or she is unable to supply the full quantity in a written or emergency oral prescription, provided the pharmacist notes the quantity supplied on the front of the prescription. The remaining portion must be supplied within 72 hours of the first partial dispensing. Otherwise, the pharmacist is obligated to notify the prescribing physician of the shortage.

Transferring prescriptions

The DEA allows the transfer of original prescription information for Schedule III, IV, and V controlled substances for the purpose of refill dispensing between pharmacies on a one-time basis. Pharmacies which electronically share a real-time, online database may transfer up to the maximum number of refills permitted by the law and authorized by the prescriber. In either type of transfer, specific information must be recorded by both the transferring and the receiving pharmacist.

The DEA does not allow for the transfer of Schedule II controlled substances, as they do not allow refills on these medications and partial fills, as discussed above, have strict limitations.

DEA number verification

Many problems associated with drug abuse are the result of legitimately-manufactured controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into the illicit drug traffic. Many of the narcotics, depressants and stimulants manufactured for legitimate medical use are subject to abuse, and have therefore been brought under legal control. The goal of controls is to ensure that these "controlled substances" are readily available for medical use, while preventing their distribution for illicit sale and abuse.

Under federal law, all businesses which manufacture or distribute controlled drugs, all health professionals entitled to dispense, administer or prescribe them, and all pharmacies entitled to fill prescriptions must register with the DEA. Authorized registrants receive a "DEA number". Registrants must comply with a series of regulatory requirements relating to drug security, records accountability, and adherence to standards.

A DEA number is a series of numbers assigned to a health care provider (such as a dentist, physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) allowing them to write prescriptions for controlled substances. Legally the DEA number is solely to be used for tracking controlled substances. The DEA number, however, is often used by the industry as a general "prescriber" number that is a unique identifier for anyone who can prescribe medication.

- 2 letters and 7 digits

- The first letter is always an A (deprecated), B (most common), or F (new) for a dispenser. (Also M is available for mid-level practitioners in some states and either P or R is used for a wholesaler)

- The second letter is typically the initial of the registrant's last name

- The seventh digit is a "checksum" that is calculated as:

- Add together the first, third and fifth digits

- Add together the second, fourth and sixth digits and multiply the sum by 2

- Add the above 2 numbers

- The last digit (the ones value) of this last sum is used as the seventh digit in the DEA number

Record keeping requirements

Every pharmacy must maintain complete and accurate records on a current basis for each controlled substance purchased, received, distributed, dispensed, or otherwise disposed of. These records must be maintained for 2 years. It is also required that records and inventories of Schedule II and Schedule III, IV, and V drugs must be maintained separately from all other records or be in a form that is readily retrievable from other records. The "readily retrievable" requirement means that records kept by automatic data processing systems or other electronic means must be capable of being separated out from all other records in a reasonable time. In addition, some notation, such as a 'C' stamp, an asterisk, red line, or other visually identifiable mark must distinguish controlled substances from other items.

Inventory requirements

A pharmacy is required by the DEA to take an inventory of controlled substances every 2 years (biennially). This inventory must be done on any date that is within 2 years of the previous inventory date. The inventory record must be maintained at the registered location in a readily retrievable manner for at least 2 years for copying and inspection by the Drug Enforcement Administration. An inventory record of all Schedule II controlled substances must be kept separate from those of other controlled substances. Submission of a copy of any inventory record to the DEA is not required unless requested.

When taking the inventory of Schedule II controlled substances, an actual physical count must be made. For the inventory of Schedule III, IV, and V controlled substances, an estimate count may be made. If the commercial container holds more than 1000 dosage units and has been opened, however, an actual physical count must be made.

Theft or loss of controlled substances

In the event that controlled substances are stolen, or are found to be missing a pharmacy should:

- contact the local police and the DEA,

- fill out and file DEA form 106.

The DEA form 106 is available as both a printed form, or may be filed electronically. To obtain the printed form click here and printout the PDF. To file elctronically proceed to https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/webforms/dtlLogin.jsp .

The DEA requires that theft of controlled substances must be reported within 24 hours.

State regulations

Many states have additional regulations for controlled substances. It is a necessary to know the differences that exist in your state. Some examples include:

- Some states have made additional drugs scheduled medications such as Arkansas and Kentucky have made tramadol a controlled substance.

- Many states, such as Pennsylvania, treat schedule V prescriptions the same as schedule III and IV prescriptions with regards to refill limits and totally quantity that may be prescribed at a time.

- Various states, such as New York, limit schedule II prescriptions to a 30 day supply.

- Some states, such as Hawaii and Montanna, currently do not allow e-prescribing of controlled substances.

Be aware of the differences with regards to controlled substances in the states you practice in and remember that the expectation when state and federal law appear to be in conflict is that you will follow the stricter regulation.

Restricted drug programs

There are a number of medications with restrictions due to patient safety concerns. The FDA primarily manages these medications through their Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) initiative. The FDA may require manufacturers of drugs with safety concerns to submit a REMS program at the time a new drug is approved. These programs may contain any combination of 5 criteria (Medication Guide, Communication Plan, Elements to Assure Safe Use, Implementation System, and Timetable for Submission of Assessments). Restricted access programs are considered Elements to Assure Safe Use. A current list of medications with REMS programs can be found at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm.

Some of the medications with the most significant restrictions include thalidomide, clozapine, buprenorphine, and isotretinoin. These programs are intended to make sure that the patients are using the medications appropriately and to monitor them for undesirable side effects.

Thalidomide

Thalidomide was first developed in Germany as a sleep aid and shortly after entering the European market, the manufacturer decided it was also good for treating morning sickness. Unfortunately, the drug caused severe and life-threatening birth defects in 40% of infants. In 1998 thalidomide was approved for limited distribution in the United States for treating multiple myeloma. It is also used to treat erythema nodosum leprosum.

Thalidomide is only available through the THALOMID REMS program. Prescribers must be certified with program, patients must comply with the strict guidelines of the program, and pharmacies must be certified with the program. Pharmacies must only dispense to patients that are authorized to receive the drug and comply with the requirements.

Clozapine

Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic medication used in the treatment of schizophrenia, and is also sometimes used off-label for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Clozapine carries many warnings, including warnings for agranulocytosis, CNS depression, leukopenia, neutropenia, seizure disorder, bone marrow suppression, dementia, hypotension, myocarditis, orthostatic hypotension (with or without syncope) and seizures.

With these severe side effects in mind each of the manufacturers are required to enroll patients taking their medication into a national registry where they will monitor a patient's white blood cell count (WBC) and their absolute neutrophil count (ANC). If the numbers fall below a particular level their therapy may need to be halted and the national registry has a responsibility to report the information to the nonrechallengeable database, that way if a physician goes to place the patient on the medication again the various manufacturers will know they are not allowed as they always need to check new orders for a patient against the nonrechallengeable database. Once listed in the nonrechallengeable database they may never use clozapine again.

Buprenorphine

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) permits physicians who meet certain qualifications to treat opioid addiction with Schedule III, IV, and V narcotic medications that have been specifically approved by the Food and Drug Administration for that indication. Such medications may be prescribed and dispensed by waived physicians in treatment settings other than the traditional Opioid Treatment Program (methadone clinic) setting.

Since there is only one narcotic medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of opioid addiction within the Schedules given, DATA 2000 basically refers to the use of buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid addiction. Methadone is a Schedule II narcotic approved for the same purpose within the highly regulated methadone clinic setting.

Under the Act, physicians may apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid addiction or dependence. Requirements include a current State medical license, a valid DEA registration number, specialty or subspecialty certification in addiction from the American Board of Medical Specialties, American Society of Addiction Medicine, or American Osteopathic Association. Exceptions were also created for physicians who participated in the initial studies of buprenorphine and for State certification of addiction specialists. However, the Act is intended to bring the treatment of addiction back to the primary care provider. Thus most waivers are obtained after taking an 8 hour course from one of the five medical organizations designated in the Act and otherwise approved by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. When a physician qualifies for the waiver, he is given a second DEA number that begins with an 'X'. This new DEA number is only to be used when prescribing buprenorphine for the purpose of treating addictions. Once a physician obtains the waiver, he or she may treat up to 30 patients for narcotic addiction with buprenorphine. Recent changes to DATA 2000 have increased the patient limit to 100 for physicians that have had their waiver for a year or more and request the higher limit in writing.

Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is indicated for severe nodular acne unresponsive to conventional therapy in patients 12 years of age and older. Isotretinoin is a teratogen and is highly likely to cause birth defects if taken by women during pregnancy or even a short time before conception. A few of the more common birth defects this drug can cause are hearing and visual impairment, missing or malformed earlobes, facial dysmorphism, and mental retardation.

Due to the teratogenicity of this product, isotretinoin is only available through a restricted program under REMS called iPLEDGE. Prescribers, patients, pharmacies, and distributors must enroll in the iPLEDGE program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com).

Phentermine and topiramate

Phentermine and topiramate (available under the brand name Qsymia) is intended to be used in combination with calorie reduction and increased physical activity to assist in chronic weight management. The combination product of phentermine and topiramate is a teratogen and is highly likely to result in either cleft palate and/or cleft lip.

Due to the teratogenic concerns associated with this product, women of childbearing age should take a pregnancy test prior to starting this therapy and they should consistently use effective contraception while taking this medication. Pharmacies must be certified by VIVUS (the manufacturer for Qsymia) to dispense the medication and as part of the mandatory REMS on this product pharmacies must handout the FDA approved Qsymia brochure that details concerns over the products teratogenicity and offers guidance on effective birth control options.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990

While most federal laws provide the pharmacist with guidance on handling pharmaceuticals, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90) placed expectations on the pharmacist in how to interact with the patient. While the primary goal of OBRA-90 was to save the federal government money by improving therapeutic outcomes, the method to achieve these savings was implemented by imposing on the pharmacist counseling obligations, prospective drug utilization review (ProDUR) requirements, and record-keeping mandates.

The OBRA-90 ProDUR language requires state Medicaid provider pharmacists to review Medicaid recipients' entire drug profile before filling their prescription(s). The ProDUR is intended to detect potential drug therapy problems. Computer programs can be used to assist the pharmacist in identifying potential problems. It is up to the pharmacists' professional judgment, however, as to what action to take, which could include contacting the prescriber. As part of the ProDUR, the following are areas for drug therapy problems that the pharmacist must screen:

- Therapeutic duplication

- Drug–disease contraindications

- Drug–drug interactions

- Incorrect drug dosage

- Incorrect duration of treatment

- Drug–allergy interactions

- Clinical abuse/misuse of medication

OBRA-90 also required states to establish standards governing patient counseling. In particular, pharmacists must offer to discuss the unique drug therapy regimen of each Medicaid recipient when filling prescriptions for them. Such discussions must include matters that are significant in the professional judgment of the pharmacist. The information that a pharmacist may discuss with a patient is found in the enumerated list below.

- Name and description of the medication.

- Dosage form, dosage, route of administration, and duration of drug therapy.

- Special directions and precautions for preparation, administration, and use by the patient.

- Common severe side effects or adverse effects or interactions and therapeutic contraindications that may be encountered.

- Techniques for self-monitoring of drug therapy.

- Proper storage.

- Refill information.

- Action to be taken in the event of a missed dose.

Under OBRA-90, Medicaid pharmacy providers also must make reasonable efforts to obtain, record, and maintain certain information on Medicaid patients. This information, including pharmacist comments relevant to patient therapy, would be considered reasonable if an impartial observer could review the documentation and understand what has occurred in the past, including what the pharmacist told the patient, information discovered about the patient, and what the pharmacist thought of the patient's drug therapy. Information that would be included in documented information are listed below.

- Name, address, and telephone number.

- Age and gender.

- Disease state(s) (if significant)

- Known allergies and/or drug reactions.

- Comprehensive list of medications and relevant devices.

- Pharmacist's comments about the individual's drug therapy.

While OBRA-90 was geared to ensure that Medicaid patients receive specific pharmaceutical care, the overall result of the legislation provided that the same type of care be rendered to all patients, not just Medicaid patients. The individual states did not establish 2 standards of pharmaceutical care-one for Medicaid patients and another for non-Medicaid patients. The end result is that all patients are under the same professional care umbrella requiring ProDUR, counseling, and documentation.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is the most significant piece of federal legislation to affect pharmacy practice since OBRA-90.

The Privacy Rule component of HIPAA took effect on April 14, 2003, and was the first comprehensive federal regulation designed to safeguard the privacy of protected health information (PHI). Pharmacies that maintain patient information in electronic format or conduct financial and administrative transactions electronically, such as billing and fund transfers, must comply with HIPAA.

While HIPAA places stringent requirements on pharmacies to adopt policies and procedures relating to the protection of patient PHI, the law also gives important rights to patients. These rights include the right to access their information, the right to seek details of the disclosure of information, and the right to view the pharmacy's policies and procedures regarding confidential information.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) imposes 5 key provisions upon pharmacies.

- The first provision is the requirement that each pharmacy take reasonable steps to limit the use of, disclosure of, and the requests for PHI. PHI is defined as individually identifiable health information transmitted or maintained in any form and via any medium. To be in compliance, a pharmacy must implement reasonable policies and procedures that limit how PHI is used, disclosed, and requested for certain purposes. The pharmacy also is obligated to post its entire notice of privacy practices at the facility in a clear and prominent location and on its Web site (if one exists).

- The second component of HIPAA requires that individuals be informed of the privacy practices of the pharmacy and that the pharmacy develop and distribute a notice with a clear explanation of these rights and practices. This notice must be given to every individual no later than the date of the first service provided, which usually means the first prescription dispensed to the patient. The pharmacist also is obligated to make a good-faith effort to obtain the patient's written acknowledgment of the receipt of the notice.

- Under the third component, pharmacies are required, as well, to select a compliance officer who will manage and ensure compliance with HIPAA.

- As part of the fourth component of HIPAA, all employees working in the pharmacy environment in which PHI is maintained must receive training on the regulations within a reasonable time after being hired. This training necessarily includes pharmacists, technicians, and any other individuals who assist in the pharmacy.

- Finally, in some situations, it is necessary for the pharmacy to allow disclosure of PHI to a person or organization that is known under HIPAA as a "business associate." Typically, business associates perform a function that requires disclosure of PHI such as billing services, claims processing, utilization review, or data analysis. Under HIPAA, a pharmacy is allowed to disclose PHI to a business associate if the pharmacy obtains satisfactory assurances, usually in the form of a contract, that the business associate will use the information only for the purposes for which it was engaged by the pharmacy.

HIPAA also provides security provisions. These security provisions went into effect April 20, 2005, almost 2 years after the privacy provisions. The security standards are designed to protect the confidentiality of PHI that is threatened by the possibility of unauthorized access and interception during electronic transmission. Like the privacy provisions, any pharmacy that transmits any health information in electronic form is required to comply with the security rules.

In particular, the security standards define administrative, physical, and technical safeguards that the pharmacist must consider in order to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI.

A unique aspect of the security provisions is that they include both "required and addressable" implementation specifications. Required implementation specifications are those that must be met, whereas, in addressable specifications, the pharmacy must determine whether the suggested safeguards are reasonable and appropriate, given the size and capability of the organization as well as the risk.

While cost may be a factor that a covered entity may consider in determining whether to implement a particular specification, nonetheless a clear requirement exists that adequate security measures be implemented. Cost considerations are not meant to exempt covered entities from this responsibility.

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act) of 2009 provided additional privacy provisions and penalties to HIPAA when dealing with electronic protected health information (ePHI). Electronic protected health information is individually identifiable health information that is created, stored, transmitted, or received electronically. The portions that affect the HIPAA regulation on pharmacy the most are the breach reporting requirements and the financial penalties for data breaches. If a breach of ePHI occurs, the affected individuals must be notified. If the unsecured ePHI of more than 500 individuals is reasonably believed to have been, accessed, acquired, or disclosed during such a breach, the HITECH Act requires HIPAA covered entities to report this breach to Health and Human Services (HHS) and the media, in addition to notifying the affected individuals.

The penalties outlined in the HITECH Act for violating the privacy provision range from $100 to $1,500,000 based on the type of disclosure, the root cause, and the number of individuals affected.

Drug recalls

Anyone that watches television, surfs the web, or flips through magazines and journals is very familiar with advertising for pharmaceuticals picturing attractive, healthy and active people. Prescriptions and over the counter medications are safely used by millions of consumers for various ailments, diseases and medical conditions everyday. While many great things have been accomplished by the development of so many medications and the marketing to millions of consumers, there are also serious side effects or other undesired results. In some cases, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or manufacturer may recall or withdraw a specific batch or completely remove a medication from the market.

What is a drug recall?

Recalls are, with a few exceptions, voluntary on the part of the manufacturer. However, once the FDA requests a manufacturer recall a product, the pressure to do so is substantial. The negative publicity from not recalling would significantly damage a reputation, and the FDA could take the manufacturer to court where criminal penalties could be imposed. The FDA can also require recalls in certain instances with infant formulas, biological products, and devices that pose a serious health hazard. Manufacturers may of course recall drugs on their own and do so from time to time for any number of reasons.

Recall classifications

There are three drug recall classifications.

Class I

- Reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, a violative product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death.

- An example would include the diet aid Fen-Phen (fenfluramine/phentermine) which caused irreparable heart valve damage and pulmonary hypertension.

Class II

- Use of, or exposure to, a violative product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences or where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.

- An example would include a medication that is under-strength but that is not used to treat life-threatening situations.

Class III

- Use of, or exposure to, a violative product that is not likely to cause adverse health consequences.

- Examples might be a container defect (plastic material delaminating or a lid that does not seal), off-taste or incorrect color, and simple text errors such as the incorrect expiration date on the manufacturer's bottle.

How drug recalls work

When an FDA-regulated product is either defective or potentially harmful, recalling that product, removing it from the market or correcting the problem is the most effective means for protecting the public. This is a multi-step process.

Step 1: Reports of adverse effects

FDA first hears about a problem product in several ways:

- A company discovers a problem and contacts the FDA.

- The FDA inspects a manufacturing facility and determines the potential for a recall.

- The FDA receives reports of health problems through various reporting systems.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contacts the FDA.

After receiving enough reports of adverse effects or misbranding it decides the product is a threat to the public health and it contacts the manufacturer to recommend a recall.

Step 2: Manufacturer agrees to recall

Provided the manufacturer agrees to a recall, they must establis a recall strategy with the FDA that addresses the depth of the recall, the extent of the public warnings, and a means for checking the effectiveness of the recall. The depth of the recall is identified by wholesale, retail, or consumer levels.

Step 3: Customers contacted

Once the strategy is finalized the manufacturer contacts it customers (pharmacies, wholesalers, etc.) with the following information:

- the product name, size, lot number, code or serial number, and any other important identifying information,

- reasons for the recall and the hazard involved, and

- instructions on what to do with the, beginning with ceasing distribution.

Step 4: Recall listed publicly

FDA recalls are listed in the FDA's weekly enforcement report ( http://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/EnforcementReports/default.htm ), see recent recalls at http://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/default.htm , and you can receive email alerts at https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/USFDA/subscriber/new?topic_id=USFDA_48 . Many subscription services, such as Medscape and Drug Facts and Comparisons eAnswers, also include drug recall information.

Step 5: Effectiveness checks

FDA evaluates whether all reasonable efforts have been made to remove or correct a product. A recall is considered complete after all of the company’s corrective actions are reviewed by FDA and deemed appropriate. After a recall is completed, FDA makes sure that the product is destroyed or suitably reconditioned, and investigates why the product was defective in the first place.

10 worst drug recalls in the United States

To emphasize the importance of drug recalls let's look at what are commonly considered the 10 worst drug recalls in U.S. history.

Fen-Phen (fenfluramine and phentermine)

- Manufacturer: Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories (formerly American Home Products)

- Recall date: 1997 (after 24 years on the market)

- Financial damage: Over $21 billion (awards to victims are close to $14 billion), making it one of the most costly products liability cases in history.

Fen-Phen’s was a ver popular anorectant. It is estimated that as many as 6.5 million people took it to help fight obesity. After consumers began experiencing rare heart valve deffects and pulmonary hypertension problems, the FDA set the recall in motion. American Lawyer reported that more than 50,000 Fen-Phen victims have filed suits against Fen-Phen’s maker Wyeth, and legal expenses combined with awards are believed to have exceeded $21 billion. Its 24 years in the marketplace combined with the severity of both the public reaction and the significant awards granted to its victims make its impact unprecedented.

Diethylstilbestrol (a.k.a., DES)

- Manufacturer: Multiple manufacturers (DES was never patented as it was created with British public funds)

- Recall date: 1975 (after 37 years on the market)

- Financial damage: Unknown quantity of financial reparations in the billions, but difficult to fully quantify since each manufacturer paid out legal damages correlated with its respective market share (a new way of awarding damages in these cases).

DES was prescribed for more than thirty years to prevent miscarriages and other complications during pregnancy. It was not until 1971 before it was connected to a rare tumor that kept appearing in the daughters of women who had taken it. The FDA only banned DES prescriptions to women because no such problems have been found in men. In fact, it can still be prescribed to men to treat estrogen deficiency. Litigation over DES led to a landmark products liability award that heavily influenced how both the courts and the FDA approach oversight of drugs with multiple manufacturers.

Baycol (cerivastatin)

- Manufacturer: Bayer A.G.

- Recall date: 2001 (after four years on the market)

- Financial damage: $1.2 billion

Baycol (cerivastatin) is a synthetic member of the class of statins, used to lower cholesterol and prevent cardiovascular disease. It was withdrawn from the market in 2001 because of the high rate of serious side-effects.

Cerivastatin was marketed by the pharmaceutical company Bayer A.G. in the late 1990s as a new synthetic statin, to compete with Pfizer's highly successful Lipitor (atorvastatin).

During post-marketing surveillance, 52 deaths were reported in patients using cerivastatin, mainly from rhabdomyolysis and its resultant renal failure. Risks were higher in patients using fibrates (mainly gemfibrozil) and in patients using the high (0.8 mg/day) dose of cerivastatin. Another 385 nonfatal cases of rhabdomyolysis were reported. This put the risk of this (rare) complication at 5-10 times that of the other statins.

Vioxx (rofecoxib)

- Manufacturer: Merck

- Recall date: 2004 (after five years on the market)

- Financial damage: nearly $6 billion in litigation-related expenses alone

Rofecoxib is a NSAID developed by Merck & Co. to treat osteoarthritis, acute pain conditions, and dysmenorrhoea. Rofecoxib was approved as safe and effective by the FDA on May 20, 1999 and was subsequently marketed under the brand name Vioxx.

Rofecoxib gained widespread acceptance among physicians treating patients with arthritis and other conditions causing chronic or acute pain. Worldwide, over 80 million people were prescribed rofecoxib at some time.

During the post-marketing phase the VIGOR and the APPROVe study both showed dramatic increases in myocardial infarctions. There is even evidence that the authors of an article for NEJM that promoted Vioxx had seen the disturbing results of VIGOR and withheld this information in the article. In addition to its own studies, on September 23, 2004 Merck received information about new research by the FDA that supported previous findings of increased risk of heart attack among rofecoxib users.

FDA analysts estimated that Vioxx caused between 88,000 and 139,000 heart attacks, 30 to 40 percent of which were probably fatal, in the five years the drug was on the market.

Merck publicly announced its voluntary withdrawal of the drug from the market worldwide on September 30, 2004.

Bextra (valdecoxib)

- Manufacturer: G. D. Searle & Company (a subsidiary of Pfizer)

- Recall date: 2005 (after four years on the market)

- Financial damage: over $2 billion

Valdecoxib is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used in the treatment of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and painful menstruation and menstrual symptoms. It is a cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor.

Valdecoxib was manufactured and marketed under the brand name Bextra by G. D. Searle & Company. It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration on November 20, 2001, and was available by prescription in tablet form until 2005, when it was removed from the market due to concerns about possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

Rezulin (troglitazone)

- Manufacturer: Parke-Davis (which was purchased by Pfizer)

- Recall date: 2000 (after three years on the market)

- Financial damage: The manufacturer grossed $1.2 billion in sales prior to the recall.

Rezulin (troglitazone) is an anti-diabetic (NIDDM) and antiinflammatory drug, and a member of the drug class of the thiazolidinediones. In the United States, it was introduced and manufactured by Parke-Davis in the late 1990s, but turned out to be associated with an idiosyncratic reaction leading to drug-induced hepatitis. One FDA medical officer evaluating troglitazone, John Gueriguian, did not recommend its approval due to potential high liver toxicity, but a full panel of experts approved it in January 1997. Once the prevalence of adverse liver effects became known, troglitazone was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 2000.

Able Laboratories generic prescription medications

- Manufacturer: Able Laboratories

- Recall date: 2005

- Financial damage: Able Laboratories had $103 million in annual sales before recall.

On May 27, 2005 the Food and Drug Administration notified consumers and healthcare professionals of a nationwide recall of all manufactured drugs (mostly generic prescription drugs, including drugs containing acetaminophen) from Able Laboratories of Cranbury, NJ, because of serious concerns that they were not produced according to quality assurance standards. Able Laboratories subsequently ceased all production.

Inconsistencies in manufacturing by Able Laboratories resulted in both subpotent and superpotent medications.

Seldane (terfenadine)

- Manufacturer: Hoechst Marion Roussel (now Sanofi-Aventis)

- Recall date: 1997 (after 13 years on the market)

- Financial damage: Seldane was a big moneymaker for Hoechst Marion Roussel for such a long period (the year before it was pulled it sold $440 million worth of Terfenadine worldwide). In addition to its legal expenses, the loss of market share alone to drugs such as Claritin (loratadine) was steep.

Seldane (terfenadine) is an antihistamine formerly used for the treatment of allergic conditions. It was brought to market by Hoechst Marion Roussel (now Sanofi-Aventis). According to its manufacturer, terfenadine had been used by over 100 million patients worldwide as of 1990. It was superseded by fexofenadine in the 1990s due to the risk of cardiac arrhythmia caused by QT interval prolongation.

Terfenadine is a prodrug, generally completely metabolized to the active form fexofenadine in the liver by the enzyme cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 isoform. Due to its near complete metabolism by the liver immediately after leaving the gut, terfenadine normally is not measurable in the plasma. Terfenadine itself, however, is cardiotoxic at higher doses, while its major active metabolite is not. Toxicity is possible after years of continued use with no previous problems as a result of an interaction with other medications such as erythromycin, or foods such as grapefruit. The addition of, or dosage change in, these CYP3A4 inhibitors makes it harder for the body to metabolize and remove terfenadine. In larger plasma concentrations, it may lead to toxic effects on the heart's rhythm (e.g. ventricular tachycardia and torsades de pointes).

Phenylpropanolamine (a.k.a., PPA)

- Manufacturer: Multiple manufacturers (widely manufactured across the industry)

- Recall date: 2000 (at least 60 years on the market)

- Financial damage: untold millions, if not billions (one manufacture alone settled for $15 million)

Phenylpropanolamine is an ingredient used in prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drug products as a nasal decongestant to relieve stuffy nose or sinus congestion and in OTC weight control drug products to control appetite.

On May 11, 2000, FDA received results of a study conducted by scientists at Yale University School of Medicine that showed an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke (bleeding of the brain) in people who were taking phenylpropanolamine. Phenylpropanolamine has been used for many years and a very small number of people taking the drug have had strokes. The Yale study helped show that the number of people having strokes when taking phenylpropanolamine was greater than the number of people having strokes who were not taking phenylpropanolamine. Although the risk of hemorrhagic stroke is very low, FDA has significant concerns because of the seriousness of a stroke and the inability to predict who is at risk. Because of continued reports to the FDA of hemorrhagic stroke associated with phenylpropanolamine and the results of the Yale study, the FDA now feels that the risks of using phenylpropanolamine outweighs the benefits and recommends that consumers no longer use products containing phenylpropanolamine.

Posicor (mibefradil)

- Manufacturer: Roche

- Recall date: 1998 (after one year on the market)

- Financial damage: Analysts had projected $2.9 billion in sales within 4 years.

In only one year on the market, Posicor (mibefradil) was linked to 123 deaths. Considered relatively safe when taken alone, Posicor became potentially deadly when combined with any of 25 different drugs. The large number of deaths are troublesome considering that the drug was prescribed to no more than 200,000 people worldwide in the space of one year, a relatively small number. Posicor is on this list for stimulating debate surrounding policies encouraging the FDA to hasten the approval of certain drugs. It is often cited as a strong example of what can go wrong when drugs are rushed to market.

Infection control standards

Infection control is concerned with preventing nosocomial or healthcare-associated infections. It is an essential part of the infrastructure of healthcare. Infection control addresses factors related to the spread of infections within the healthcare setting (whether patient to patient, patients to staff, and staff to patient, or among staff), including prevention via hand hygiene, facility and equipment cleaning, and through the use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Hand hygiene

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards require that employers must provide readily accessible hand washing facilities, and must ensure that employees wash hands and any other skin with soap and water or flush mucous membranes with water as soon as feasible after contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials.

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter 797 states:

"...personnel perform a thorough hand-cleansing procedure by removing debris from under fingernails using a nail cleaner under running warm water followed by vigorous hand and arm washing to the elbows for at least 30 seconds with either nonantimicrobial or antimicrobial soap and water."

Cleaning facilities and equipment

Equipment and facilities for both sterile and nonsterile require cleaning and inspection.

USP 795, with regard to nonsterile compounding states:

"Equipment and accessories used in compounding are to be inspected, maintained, cleaned, and validated at appropriate intervals to ensure the accuracy and reliability of their performance."

Since environmental contact is a common source of contamination with respect to compounded sterile preparations, USP 797 provides a series of standards related to buffer room/clean room, ante room/ante area, and equipment design and cleaning schedules for facilities and equipment used for assembling CSPs. Primary engineering controls (i.e., laminar airflow workbenches, biological safety cabinets, and barrier isolators) which are intimate to the exposure of critical sites, require disinfecting more frequently than do the actual room surfaces such as walls and ceilings.

Cleaning and disinfecting primary engineering controls are the most critical practices before the preparation of CSPs. Such surfaces shall be cleaned and disinfected frequently, including at the beginning of each shift, prior to each batch preparation, every 30 minutes during continuous compounding periods of individual CSPs, when there are spills, and when surface contamination is known or suspected.

With respect to the rooms involved in preparing CSPs, counters and easily cleanable work surfaces must be cleaned daily. Walls, ceilings, and storage shelving must be cleaned on a monthly basis.

Personal protective equipment

When assembling CSPs, preparers should don personal protective equipment (PPE) to further minimize the likelihood that they will contaminate the final product. USP 797 provides requirements for how personnel should wash and garb including the order that they should don their PPE, from dirtiest to cleanest. First, personnel should remove unnecessary outer garments and visible jewelry (scarves, rings, earrings, etc.). Next, they should don shoe covers, facial hair and hair covers, and masks (optionally they may include a face shield). Next, they must perform appropriate hand hygiene. After hand washing, a nonshedding gown with sleeves that fit snugly around the wrists should be put on. Once inside the buffer area an antiseptic hand cleansing using a waterless alcohol-based hand scrub should be performed. Sterile gloves are the last item donned prior to compounding.

Professional standards in pharmacy

Pharmacy professionals, including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and other pharmacy employees, are expected to actively demonstrate professionalism through attitudes, qualities, and behaviors commensurate to the area of specialized knowledge that they have achieved. The following list provides an overview of these professional standards:

- The first consideration is the health and safety of the patient.

- Honesty and integrity are integral to the high moral and ethical principles of this field.

- Pharmacy technicians are expected to assist pharmacists in providing patients with safe, efficacious, and cost effective access to health resources.

- Technicians and pharmacists should respect the values of each other's abilities as well as those of colleagues and other healthcare professionals.

- Technicians and pharmacists should maintain their competencies and seek to enhance their knowledge and skills.

- Healthcare professionals need to maintain a patient's rights to dignity and confidentiality.

- Pharmacy professionals may not assist in providing medications and medical devices of poor quality that do not meet the necessary standards established by laws.

- Pharmacy professionals are not to engage in activities that would discredit the profession.

- Pharmacy professionals should engage in and support organizations that promote their professions and the enhancements of those that are in the profession.

Individual state boards of pharmacy (BOP) provide further standards for pharmacy personnel, including job responsibilities and requirements such as registration, licensure, and certification.

Facility, equipment, and supply requirements

Depending on the specific kind of pharmacy practice, various kinds of facilities, equipments, and supplies will be required. The needs of a hospital pharmacy are different from those of a community pharmacy, just as the needs of a nuclear pharmacy will be different from those of a mail order pharmacy.

All facilities will have to be clean enough to meet any state and local sanitation requirements. Facilities will need to have adequate space to perform their necessary duties. In many states, their Board of Pharmacy (BOP) will establish minimum requirements for space. They will need a properly functioning heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system to ensure that medications on the shelf are stored at controlled room temperature (15 to 30° C or 59 to 86° F). The facility will need properly maintained and monitored refrigerators (2 to 8° C or 36 to 46° F) and freezers (-25 to -10° C or -13 to 14° F) for medications that need to be stored that way.

Facilities that assemble compounded sterile preparations (CSPs) will need a primary engineering control, such as a laminar airflow workbench, with adequate support systems around it (i.e., a buffer room). According to the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter 797, if a facility prepares more than a low volume of hazardous drugs, it will need a dedicated negative pressure room. This low volume requirement will likely change whenever a proposed USP chapter 800 is completed and eventually enforced.

All pharmacies will need ready access to drug information resources. Some BOPs will place very specific requirements on what kind of drug information resources pharmacies need to carry, whereas others may simply require an adequate reference library to meet the needs of the patient population they serve. It is extremely important that whatever drug references are being utilized in a pharmacy, that they are the most up-to-date editions available.

See also

References

- The Harris Poll, Americans Less Likely to Say 18 of 19 Industries are Honest and Trustworthy This Year, December 12, 2013, http://www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/Harris%20Poll%2096%20-%202013%20Industry%20Regulation_12.12.2013.pdf

- Pharmacy Times, A Review of Federal Legislation Affecting Pharmacy Practice, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200612-01.asp

- Strauss's Federal Drug Laws and Examination Review, Fifth Edition (revised), Steven Strauss, CRC Press, 2000

- Pharmacy Times, An Overview and Update of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200702-01.asp

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Title 21 United States Code (USC) Controlled Substances Act, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/21usc/index.html

- Controlled Substance Ordering System, http://www.deaecom.gov/

- Drug Enforcement Administration Office of Diversion Control, Practitioner's Manual SECTION V – VALID PRESCRIPTION REQUIREMENTS, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/pract/section5.htm

- Medscape, A Guide to State Opioid Prescribing Plicies, http://www.medscape.com/resource/pain/opioid-policies

- DrFirst, E-Prescribing for Controlled Substances, http://www.drfirst.com/e-prescribing-for-controlled-substances.jsp

- FDA, Guidance for Industry Format and Content of Proposed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), REMS Assessments, and Proposed REMS Modifications, http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM184128.pdf

- FDA, Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm

- Medscape, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies: An Introduction for Physicians, Nurses, and Pharmacists, Claudia B. Karwoski, PharmD; Marcie A. Bough, PharmD; Todd M. Colonna, MD; Lisa A. Gorski, RN, MS, May 15, 2012, http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/762673_transcript

- ParagonRx, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) - A Brief History. September 2009, http://www.paragonrx.com/rems-hub/rems-history/

- FDA, Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers, http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/default.htm

- Wikipedia, Drug Addiction Treatment Act, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Addiction_Treatment_Act

- iPledge program, https://www.ipledgeprogram.com

- Vivus, Risk of Birth Defects with Qsymia, https://qsymia.com/wp-content/wbuploads/pdf/risk-of-birth-defects.pdf

- Pharmacy Times, A Review of Federal Legislation Affecting Pharmacy Practice, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200612-01.asp

- Strauss's Federal Drug Laws and Examination Review, Fifth Edition (revised), Steven Strauss, CRC Press, 2000

- Pharmacy Technician Practice and Procedures, Gail G. Orum Alexander and James J. Mizner, Jr., McGraw Hill, 2011