Medication order entry and fill process

From Rx-wiki

This article will cover the following major concepts related to the medication order entry and fill process:

- Order entry process

- Intake, interpretation, and data entry

- Calculate doses required

- Fill process (e.g., select appropriate product, apply special handling requirements, measure, and prepare product for final check)

- Labeling requirements (e.g., auxiliary and warning labels, expiration date, patient specific information)

- Packaging requirements (e.g., type of bags, syringes, glass, PVC, child resistant, light resistant)

- Dispensing process (e.g., validation, documentation and distribution)

Contents

- 1 Terminology

- 2 Prescription intake

- 3 Prescription translation

- 3.1 Abbreviations

- 3.2 Parts of a prescription

- 3.3 Calculations

- 3.3.1 Days' supply

- 3.3.1.1 Days' supply for tablets, capsules, and liquid medications

- 3.3.1.2 Days' supply for insulins

- 3.3.1.3 Days' Supply for inhalers and sprays

- 3.3.1.4 Days' supply for ointments and creams

- 3.3.1.5 Days' supply for ophthalmic and otic preparations

- 3.3.1.6 Days' supply for various packs

- 3.3.1.7 Days' supply for other miscellaneous medications

- 3.3.2 Adjusting refills and short-fills

- 3.3.1 Days' supply

- 4 Order entry

- 5 Filling the prescription

- 6 Medication pickup

- 7 See also

- 8 References

Terminology

To get started in this chapter, there are some terms that should be defined.

prescription origin code (POC) - Prescription origin codes (POC) were first created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to help gather data on where prescriptions come from (0 = Unknown, 1 = Written, 2 = Telephone, 3 E-prescription, 4 = Fax). POCs are now mandatory for both Medicare and Medicaid patients and many other insurance companies require this as well.

e-prescribing - E-prescribing is the computer-based electronic generation, transmission and filling of a medical prescription, taking the place of paper and faxed prescriptions. E-prescribing allows a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant to electronically transmit a new prescription or renewal authorization to a community or mail-order pharmacy.

computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) - Computerized prescriber order entry, also called computerized physician order entry, is a process of electronic entry of practitioner instructions for the treatment of patients under their care. CPOE systems are used for processing orders in institutional settings.

superscription - The superscription consists of the heading on a prescription where the symbol Rx is found. The Rx symbol comes before the inscription.

inscription - The inscription is also called the body of the prescription, and provides the names and quantities of the chief ingredients of the prescription. Also in the inscription you find the dose and dosage form, such as tablet, suspension, capsule, syrup.

signatura - The signatura (also called sig, or transcription), gives instructions on a prescription to the patient on how, how much, when, and how long the drug is to be taken. These instructions are preceded by the symbol “S” or “Sig.” from the Latin, meaning "write" or "label." Whenever translating the signatura into instructions for a patient, begin it with an action verb such as take, inhale, spray, inject, place, swish, or whatever other verb seems appropriate for the medication.

National Provider Identifier (NPI) - A National Provider Identifier is a unique 10-digit identification number issued to health care providers (physician, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, dentists, etc.) by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). An NPI is a required identifier for Medicare services, and is also used by other payors, including commercial healthcare insurers. If you need to check a find/verify a particular providers NPI, you may look it up at http://www.npinumberlookup.org.

pharmacy benefits manager (PBM) - A PBM is a company that acts as an intermediary between the pharmacy and the insurance plan.

bank identification number (BIN) - On a health insurance card a BIN is a six digit number used to identify a specific plan from a carrier making it easier for the PBM to process your prescription online. No actual bank is involved in this part of the process, the name is a hold over from early electronic banking jargon.

dispense as written (DAW) codes - DAW codes are used to provide a quick explanation of whether or not a generic version of the medication is allowed to be dispensed, and if not then why and whom deemed the brand name product to be necessary. A DAW code of '0' applies to most prescriptions as they allow for generic substitution and patients are generally willing to receive the more affordable version. If a physician requires a specific medication to be dispensed, they will typically note this on the prescription. This is considered a DAW code of '1'. Sometimes a patient may request that they receive a brand name product even if a prescriber allowed for generic substitution. This would be classified as a DAW code of '2'. Other DAW codes are less frequently used. The following is a succinct list of the other DAW codes; 3 = substitution allowed - pharmacist selected product dispensed, 4 = substitution allowed - generic drug not in stock, 5 = substitution allowed - brand drug dispensed as generic, 6 = override, 7 = substitution not allowed - brand drug mandated by law, 8 = substitution allowed - generic drug not available in marketplace, and 9 = Other.

Prescription intake

Prescription intake, which is often the responsibility of a pharmacy technician, involves both the receipt of the initial prescription and, in a community pharmacy setting, gathering pertinent patient data.

Receiving the prescription

With respect to prescription intake the first thing to address is the means by which the medication itself arrives in the pharmacy. Prescriptions may arrive on a traditional prescription form (there are specific security requirements on this if the patient is using Medicaid), a fax or phone call from an appropriately licensed prescriber, e-prescribing in an outpatient setting, and computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) in an institutional setting. These various means have various federal regulations associated with them and individual states may place additional restrictions on how they are used.

When a community pharmacy receives a prescription it is a requirement to note the source of the prescription if it is for a Medicare or Medicaid patient. As many individual insurance companies also require this information it has become a common practice for community pharmacies to track where all prescriptions come from. These prescriptions are tracked using prescription origin codes (POC) which are commonly entered into the pharmacy management software. The prescription origin codes are as follows:

0 = Unknown, this is used when the manner in which the original prescription was received is not known, which may be the case in a transferred prescription

1 = Written prescription via paper which includes computer printed prescriptions that a physician signs as well as tradition prescription forms

2 = Telephone prescription obtained via oral instruction or interactive voice response

3 = E-prescriptions securely transferred from a computer to the pharmacy

4 = Facsimile prescription obtained via fax transmission including an e-Fax where a scanned image is sent to the pharmacy and either printed or displayed on a monitor/screen

A written prescription should contain the following information at a minimum:

- the prescriber's name, address, and telephone number,

- if the order is for a controlled substance, the prescriber's DEA number,

- the patient's name, the date of issuance,

- the name of the medication or device prescribed and dispensing instructions (if necessary),

- the directions for the use of the prescription,

- any refills (if authorized),

- special labeling and other instructions, and

- the prescriber's signature.

The Medicaid Tamper-Resistant Prescription Pad Law has placed additional requirements on written prescriptions to help ensure the legitimacy of the prescriptions being received in the pharmacy. Since October 1, 2008 all Medicaid scripts must contain one or more industry recognized features from each of three categories of security as specified by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS).

Category One - One or More industry-recognized features designed to prevent unauthorized copying of a completed or blank prescription form.

- Void Pantograph background (Hidden Message Technology)

- Reverse Rx Symbol

- Micro Printing

- Artificial Watermark on back of script

- Coin Activated Ink

Category Two - One or More industry-recognized features designed to prevent the erasure or modification of information written on a prescription by the prescriber.

- Colored Shaded Pantograph background

- Toner Grip Security Coating

- Check and Balance" printed features such as "quantity" check boxes, and space to indicate "number of medications" written on prescription form

Category Three - One or More industry-recognized features designed to prevent the use of counterfeit prescription forms.

- Security Feature Warning Box and Warning Bands

- Security Back Printing

- Coin Activated Validation

- Batch Number identification

- Secure Rub Color Change Ink

- Consecutive Numbering

Physicians may, and often do, use these tamper-resistant prescriptions for their other patients as well.

Prescribers may send prescriptions to the pharmacy via a fax machine. The same requirements listed on written prescriptions apply for faxed prescriptions (although prescribers do not need to use tamper-resistant prescription pads for faxed orders), but their is an additional limitation. Schedule II medications may not be faxed under ordinary circumstances.

DEA has granted three exceptions to the fax prescription requirements for Schedule II controlled substances. The fax of a Schedule II prescription may serve as the original prescription as follows:

- A practitioner prescribing Schedule II narcotic controlled substances to be compounded for the direct administration to a patient by parenteral, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous or intraspinal infusion may transmit the prescription by fax. The pharmacy will consider the faxed prescription a "written prescription" and no further prescription verification is required. All normal requirements of a legal prescription must be followed.

- Practitioners prescribing Schedule II controlled substances for residents of Long Term Care Facilities (LTCF) may transmit a prescription by fax to the dispensing pharmacy. The practitioner’s agent may also transmit the prescription to the pharmacy. The fax prescription serves as the original written prescription for the pharmacy.

- A practitioner prescribing a Schedule II narcotic controlled substance for a patient enrolled in a hospice care program certified and/or paid for by Medicare under Title XVIII or a hospice program which is licensed by the state may transmit a prescription to the dispensing pharmacy by fax. The practitioner (or their agent) may transmit the prescription to the pharmacy. The practitioner will note on the prescription that it is for a hospice patient. The fax serves as the original written prescription.

A phone order prescription (also called a verbal order), should include all the same information as a written prescription as the pharmacist will need to reduce it to writing to later be filed with the other prescriptions. Under ordinary circumstances, Schedule II medications may not be called in.

For Schedule II controlled substances, an oral order is only permitted in an emergency situation. An emergency situation is defined as a situation in which:

- Immediate administration of the controlled substance is necessary for the proper treatment of the patient.

- No appropriate alternative treatment is available.

- Provision of a written prescription to the pharmacist prior to dispensing is not reasonably possible for the prescribing physician.

In an emergency, a practitioner may call-in a prescription for a Schedule II controlled substance by telephone to the pharmacy, and the pharmacist may dispense the prescription provided that the quantity prescribed and dispensed is limited to the amount adequate to treat the patient during the emergency period. The prescribing practitioner must provide a written and signed prescription to the pharmacist within seven days. Further, the pharmacist must notify DEA if the prescription is not received.

E-prescribing has become a very common practice. Since 2007 pharmacies have been allowed to transmit prescriptions electronically using properly certified software (i.e., SureScripts) for most legend drugs. As of June 1, 2010 physicians and pharmacies are also allowed to transmit prescriptions for Schedule II, III, IV, and V medications. While this is a recent shift in federal law, some states may still prohibit e-prescribing for controlled substances.

Through the requirement of using computer programs that communicate through SureScripts to electronically prescribe outpatient prescriptions, SureScripts has the responsibility of authenticating both the receipt and delivery of the electronic prescription. E-prescribing also allows the prescriber to verify whether or not a particular medication is covered by the patient's pharmacy benefits manager (PBM)

Prescribers are required to provide a two tier authentication of prescriptions for controlled substance. For this two tier authentication, the DEA is allowing prescribers the use of any two of the following – something you know (a knowledge factor), something you have (a hard token stored separately from the computer being accessed), and something you are (biometric information). The hard token, if used, must be a cryptographic device or a one-time password device that meets the Federal Information Processing Standard 140-2 Security Level 1. Some states may specify which tiers they specifically require for prescribing controlled substances.

Institutional settings are more likely to utilize CPOE (computerized prescriber order entry, also called computerized physician order entry) than e-prescribing. CPOE is a process of electronic entry of practitioner instructions for the treatment of patients under their care. These orders are communicated over a computer network to the medical staff or to the departments (pharmacy, laboratory, or radiology) responsible for fulfilling the order. CPOE decreases delay in order completion, reduces errors related to handwriting or transcription, allows order entry at the point of care or off-site, provides error-checking for duplicate or incorrect doses or tests, and simplifies inventory and posting of charges.

Gathering patient data

When a patient first arrives at a community pharmacy the pharmacy team will need to gather/verify various important pieces of patient data including:

- gather drug and disease information,

- ensure that the pharmacy has the correct name, address, contact information, and any other pertinent data,

- document/update allergy information

- verify/update medication insurance information

In an inpatient setting, while a pharmacy will still want all this information to be completed, it is typically the responsibility of other departments.

Prescription translation

Once the prescription has entered the pharmacy, it becomes the responsibility of the pharmacy staff to decipher and fill the medication for the patient. This will likely require the translation of various medical abbreviations and some calculation to ensure that the proper quantity is being dispensed.

Abbreviations

Prescriptions have been obfuscated by a combination of Latin and English abbreviations (sometimes they even throw in Greek words). They are commonly used on prescriptions to communicate essential information on formulations, preparation, dosage regimens, and administration of the medication. There are approximately 20,000 medical abbreviations; instead of providing an exhaustive and meaningless list, this section will focus on the most common medical abbreviations that are necessary for interpreting prescriptions and performing calculations.

The following lists are broken into five categories including route, dosage form, time, measurement, and a catch all category simply named "other." The abbreviations can often be written with or without the 'periods' and in upper or lower case letters (e.g., p.o. and PO both mean 'by mouth'). The format on these lists will be to provide the abbreviation, followed by its intended meaning.

Route

aa - affected area

a.d. - right ear

a.s. - left ear

a.u. - each ear

IM - intramuscular

IV - intravenous

IVP - intravenous push

IVPB - intravenous piggyback

KVO - keep vein open

n.g.t. - naso-gastric tube

n.p.o. - nothing by mouth

nare - nostril

o.d. - right eye

o.s. - left eye

o.u. - each eye

per neb - by nebulizer

p.o. - by mouth

p.r. - rectally

p.v. - vaginally

SC or SQ - subcutaneously

S.L. - sublingually (under the tongue)

top. - topically

Some additional notes on these routes of administration are necessary. The abbreviation 'a.d.' if written without periods, ad, can also mean to or up to. Also, subcutaneously can be abbreviated as 'SC' or 'SQ'. While amongst health care professionals we would use the phrase sublingual as a route of administration, it may be necessary to translate 'SL' as 'under the tongue' for many patients.

Dosage form

amp. - ampule

aq or aqua - water

caps - capsule

cm or crm - cream

elix. - elixir

liq. - liquid

sol. - solution

supp. - suppository

SR, XR XL - slow/extended release

syr. - syrup

tab. - tablet

ung. or oint - ointment

The abbreviation 'cm' can be translated as either 'cream' or 'centimeter'. Use context clues from the rest of the prescription to determine which translation is appropriate.

Time or how often

a.c. - before food, before meals

a.m. - morning

atc - around the clock

b.i.d. or bid - twice a day

b.i.w. or biw - twice a week

h or ° - hour

h.s. - at bedtime

p.c. - after food, after meals

p.m. - evening

p.r.n. or prn - as needed

q.i.d. or qid - four times a day

q - each, every

q.d. - every day

q_h or q_° - every__hour(s) (i.e., q8h would be translated as every 8 hours)

qod - every other day

stat - immediately

t.i.d. or tid - three times a day

t.i.w. or tiw - three times a week

wa - while awake

Measurement

i, ii, ... - one, two, etc. (often Roman numerals will be written on prescriptions using lowercase letters with lines over top of them)

ad - to, up to

aq. ad - add water up to

BSA - body surface area

cc - cubic centimeter

dil - dilute

f or fl. - fluid

fl. oz. - fluid ounce

g, G, or gm - gram

gr. - grain

gtt - drop(s)

l or L - liter

mcg or μg - microgram

mEq - milliequivalent

mg - milligram

ml or mL - milliliter

q.s. - a sufficient quantity

q.s. ad - add a sufficient quantity to make

ss - one-half (commonly used with Roman numerals to add a value of 0.5)

Tbs or T - tablespoon

tsp or t - teaspoon

U - unit

> - greater than

< - less than

Other

c - with

disp. - dispense

n/v - nausea and vomiting

neb - nebulizer

NR - no refills

NS or NSS - normal saline, normal saline solution

s - without

Sig or S - write, label

SOB - shortness of breath

T.O. - telephone order

ut dict or u.d. - as directed

V.O. - verbal order

Parts of a prescription

Traditionally, a prescription is a written order for compounding, dispensing, and administering drugs to a specific client or patient and once it is signed by the physician it becomes a legal document. Prescriptions are required for all medications that require the supervision of a physician, those that must be controlled because they are addictive and carry the potential of being abused, and those that could cause health threats from side effects if taken incorrectly, for example, cardiac medications, controlled substances, and antibiotics.

The following is a list of the parts of a prescription:

- Patient Information, which may include information such as name, address, age, weight, height, and allergies.

- Superscription, which is the 'Rx' symbol that we typically translate as, "Take thus."

- Inscription, which is the actual medication or compounding request.

- Subscription, or how much to dispense.

- Signatura, which is the instruction set intended for the patient.

- Date, this is when the prescription was written. prescriptions for medications and supply that are not considered controlled substances are good for up to 1 year from when the prescription was written.

- Signature lines, which is where the prescriber provides their signature and indicates their degree. Often, this is also where a prescriber may indicate their preferences with regard to generic substitution.

- Prescriber information, which includes the physician's name, practice location address, telephone number and fax number. This may also include the prescriber's NPI number and appropriate license numbers.

- DEA#, DEA numbers are required for controlled substances.

- Refills, which simply indicates how many refills may be supplied for a particular medication.

- Warnings, which are provided by the prescriber with the intention of emphasizing specific concerns.

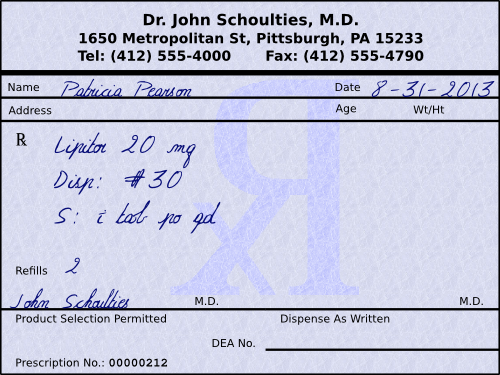

So, if we look at a prescription for Patricia Pearson (see below), we can see that it is for Lipitor (atorvastatin Ca) 20 mg tablets, and that the patient is to receive 30 of them with 2 refills. The instructions to the patient would be, “Take 1 tablet by mouth daily.”

Other things of note include the date that the prescription is written for is August 31, 2013. Prescriptions for non-controlled substances are only good for one year, so Mrs. Pearson will need a new script if she still needs this medication past August 31, 2014, regardless of how many refills were written for. Another noteworthy item is that the physician signed permitting product selection (i.e., generic substitution). The last significant item on this label is that the physician did not include their DEA number. A DEA number should only be used for controlled substances.

Besides over the counter medications (OTC) such as aspirin and ibuprofen, behind the counter medications (BTC) such as Allegra-D (fexofenadine with pseudoephedrine), and prescription medications (Rx legend) such as amoxicillin and digoxin, there is another group of medications to be concerned with called controlled substances. Controlled substances are medications with further restrictions due to abuse potential. There are 5 schedules of controlled substances with various prescribing guidelines based on abuse potential, as determined by the Drug Enforcement Administration and individual state legislative branches. CI medications are not available via a prescription. CII medications may be written for a maximum 90 day supply excluding hospice patients. No refills are allowed on schedule II medications. CIII-IV medications may only be written for a 6 month supply. CV medications may be written for up to 1 year, although many states limit this to 6 months.

Calculations

Various calculations involved in correctly interpreting prescriptions frequently need to be performed to account for days' supply, adjusting refills and short-fills. Prescribers often just include a quantity of medication to dispense and directions on how frequently to use it. They usually don't include the actual intended time frame. When prescribers write these prescriptions they may have various time frames in mind which sometimes differ from the period of time required by a specific prescription benefits manager.

Days' supply

Physicians often just include a quantity of medication to dispense and directions on how frequently to use it. They usually don't include the actual intended time frame. As a pharmacy technician, you will need to translate that into Days' Supply.

In this chapter, Days' Supply is referring to how long a prescription order will last. Often it is not as simple as giving a tablet once a day for 30 days; you will frequently need to do calculations for oral liquid medications, injectables, nasal sprays, and inhalers, and make estimations for PRN's, ointments and creams, lotions, eye and ear drops, and ophthalmic ointments.

Days' supply for tablets, capsules, and liquid medications

The first things to look at are tablets, capsules, and liquid medications because they're the most common and the most straight-forward to perform calculations with. Without wanting to over explain this process, let's look at some example problems.

Example: A prescription is written for amoxicillin 250 mg capsules #30 i cap t.i.d. What is the days' supply?

Example: A prescription is written for amoxicillin 250 mg/5 mL 150 mL i tsp tid. What is the days' supply?

The item to be careful about when it comes to tablets, capsules, and liquid medications are PRN medications, especially ones with variable doses and variable frequencies. In general, you should perform the calculations using the shortest interval with the highest dose. This will provide the shortest span of time in which they could use all the medication dispensed. Let's look at an example problem.

Example: A prescription is written for Ultram 50 mg #60 i-ii tabs po q4-6h prn pain. What is the days' supply?

Conveniently, this example came out to an even number of days. Sometimes your calculations will come out to a decimal number of days and you may need to use some professional judgement to determine whether to drop the decimal or round up. If you are not sure, it is usually better to drop the decimal.

Days' supply for insulins

Most insulins are called U-100 insulins meaning that each mL contains 100 units. Also most insulin vials are either 10 mL vials or boxes of 5 syringes containing 3 mL in each syringe for a total of 15 mL in a box. A 10 mL vial of U-100 strength insulin would contain 1000 units and a 15 mL box of syringes with U-100 insulin would contain 1500 units. This is good information to help you make quick work of the vast majority of insulin calculations. With insulin problems, whenever you come out with a decimal number of days you should always just drop the decimal as you never want a diabetic patient to run out of their insulin. The last thing to keep in mind with respect to an insulin vial is that it should not be kept for longer than 30 days after it has been opened. Determining how long a box will last is different since each syringe is only good for 30 days after it is started, but there are five syringes. Let's look at an example problem with insulin.

Example: A prescription is written for Humulin N U-100 insulin 10 mL 35 units SC qd. What is the days' supply?

![]()

Which means 28 days because you should drop the decimal.

Days' Supply for inhalers and sprays

Whenever you see instructions on a product for a patient to receive a particular number of sprays or puffs of a given drug, you should stop and actually look at the packaging to discover how many metered inhalations or how many metered sprays are actually in the container. Lets look at an example problem accompanied by some of the text from the front of the container.

Example: A prescription is written for ProAir HFA 8.5 g inhaler 2 puffs q.i.d. What is the days' supply? (Additional information from medication package: 200 metered inhalations; 8.5 g net contents)

Days' supply for ointments and creams

Calculations for creams and ointments are a little more tricky because you usually don't know exactly how much will be used in a dose. The amount will depend on how large of an area is affected and how many areas it needs to be applied to. The amount applied usually does not exceed 500 mg to 1 g, so unless you know otherwise, use 1 gram for the dose for each affected area.

Example: A prescription is written for Mycolog II cream 15 g apply sparingly bid. What is the days' supply?

Only 500 mg per dose is used in the calculation because the prescription specifically requested for it to be applied sparingly.

Days' supply for ophthalmic and otic preparations

To solve this type of problem, you need to know a conversion factor from milliliters to drops. Unfortunately (or fortunately since most students despise the apothecary system), you cannot use the conversion from the apothecary system. The USP in chapter 1101 has written guidelines on the standardization of medicine droppers. Unless your specific medication notes something different, a dropper should be calibrated by the manufacturer to deliver between 18 and 22 drops per milliliter. Most people just split the difference and estimate 20 gtt/mL. With that in mind, we can get a good estimate on how long the medication should last.

Another odd thing to keep track of when dealing with eye preparations are ophthalmic ointments. An ophthalmic ointment is typically applied as a very thin strip. Treat each dose of an ophthalmic ointment as 100 mg. Let's look at some example problems with respect to ophthalmic and otic preparations.

Examples: A prescription is written for timolol 0.25% Ophth. Sol. 5 mL i gtt ou q.d. What is the days' supply?

Example: A prescription is written for Neosporin Ophth. ung 3.5 g apply a thin strip ou q3-4h wa. What is the days' supply?

It is noteworthy that the request was to only apply the medication while awake. The standard expectation is for the patient to sleep 8 hours per day and therefor be awake for 16 hours a day. Under this expectation, the patient will likely receive 5 doses each day.

Days' supply for various packs

Many medications (such as birth control, steroids, and antibiotics) may come in packs with very explicit instructions for use. These instructions often explain exactly how many days they will last and require no additional calculations. You must simply read the instructions on the package to know how long it will last. Let's look at an example problem.

Example: A prescription is written for methylprednisolone 4 mg tabs taper pack use as directed. What is the days' supply?

The package has the following dosing information written on it:

1st Day: Take 2 tablets before breakfast, 1 tablet after lunch and after supper, and 2 tablets at bedtime.

2nd Day: Take 1 tablet before breakfast, 1 tablet after lunch and after supper, and 2 tablets at bedtime.

3rd Day: Take 1 tablet before breakfast and 1 tablet after lunch, after supper, and at bedtime.

4th Day: Take 1 tablet before breakfast, after lunch, and at bedtime.

5th Day: Take 1 tablet before breakfast and at bedtime.

6th Day: Take 1 tablet before breakfast.

It requires nothing more than observation to realize it will last 6 days.

Days' supply for other miscellaneous medications

Unfortunately, there are many medications that have their own specific rules, such as estrogens given for hormone replacement therapy that are cycled on and off. The cycle is days 1-25 on, followed by five days off or it may be cycled for three weeks on, followed by one week off. Items like a vial of nitroglycerin sublingual tablets or spray are expected to last a patient 30 days. With items, like vaginal preparations, you'll need to know how much is delivered via the applicator. Lotions can be a challenge depending on their viscosity. A good rule of thumb for a lotion is to expect 2 mL to be used on each affected area per application. As you can tell, there are many individual little rules to try and work with when estimating how long a particular medication will last.

Adjusting refills and short-fills

The amount of medication a pharmacy can dispense to a patient is restricted first, by the prescriber's guidelines and second by the insurer's guidelines. As previously mentioned in this chapter, when prescribers write these prescriptions they may have various time frames in mind which sometimes differ from the period of time required by a specific prescription benefits manager. Calculations are often needed to first adjust the quantity dispensed to comply with the insurer's guidelines, and then the number of refills allowed.

To avoid over explaining this, let's look at a couple of example problems.

Example: A prescription is written for Dyazide #50 i cap p.o. q.d. + 3 refills. The insurance plan has a 30 day supply limitation. How many capsules can be dispensed using the insurance plan guidelines and how many refills are allowed with the adjusted quantity?

First calculate the total number of capsules allowed by the prescriber:

Then, using dimensional analysis we can figure out how many capsules will be needed for each fill.

Next, using dimensional analysis we can figure out how many fills from the insurer will be required to dispense the quantity written for by the physician.

Therefore, there will be 5 refills after the initial fill is dispensed, but there is still a partial fill left.

Now, based on the information we have already determined, we will figure out how many capsules to dispense for the partial fill.

Now, let's restate everything in short:

We are dispensing 30 caps for our initial fill.

The patient can have 5 refills of 30 caps,

and a partial fill of 20 caps.

Order entry

Once the information on a particular prescription has been accurately interpreted, it will need to be entered into the pharmacy software management system. To cover this we should look at what pharmacy software management systems entail and what kind of information will need to be entered to process the prescription.

Pharmacy management software systems

In order to process the prescription, it will need to be entered into a pharmacy management software system. Pharmacy management software systems are not standardized in appearance, which allows companies to compete with each other to try and implement their own vision as to how an integrated environment should look and feel for the end users. This translates into a plethora of competing systems on the market. You'll find that most pharmacies have chosen different systems, but no matter what they look like they need to manipulate the same data.

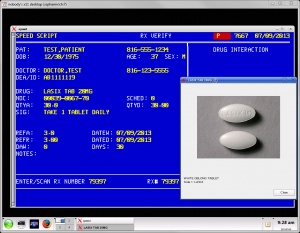

When comparing systems, the first thing you'll notice about pharmacy software is that some programs have chosen very different user interface paradigms. For most programs there are two types of interfaces: text-based user interfaces (somewhat reminiscent of DOS style programs in appearance) or GUI (pronounced goo-ey and stands for graphical user interface).

Text-based user interfaces have the advantages that they can usually be run on older hardware successfully and don't require as much network bandwidth. These types of interfaces tend to be faster and rely primarily on keyboard input. Most of these programs have been around a long time so they tend to be very mature and have relatively few software bugs. The down side is that newer employees tend to be intimidated by text-based user interfaces as they have grown accustomed to GUI interfaces in most of their interactions with software.

GUIs have the advantage that they are primarily point and click software relying largely on mouse usage along with keyboard input for text boxes (some GUIs are looking at possible transitions to incorporating touch interfaces). This kind of software may be installed locally or remotely depending on the offerings from the manufacturer and software's specific design. These systems will typically require more overhead when compared to text-based user interfaces but staff often finds them less intimidating.

Some companies attempt to create software that can bridge the gap between these two paradigms. Speed Script, pictured to the right, combines elements of both.Most pharmacy management systems are capable of performing the following tasks:

- prescription processing

- e-prescribing

- prescription pick-up with signature capture

- refill queue

- workflow manager

- prescription scanning and patient card scanning

- med guides, care points, and REMS

- NDC check and prescription verification processing

- third party adjudication including major medical insurance and worker’s comp * billing

- accounts receivable processing

- point of sale capabilities

- DME/CMS 1500 on-line billing

- 340B inventory control management and reports

- wholesaler interface with automated ordering

- nursing home and LTC batch processing

- wireless signature capture/delivery manifest module

- MTM services billing electronically

- compounding services support

A major challenge to any pharmacy when choosing a pharmacy management system is pricing along with per-seat licensing, types of tech support and maintenance, local servers versus remote hosting, accessing systems with a local client compared to a web browser compared to virtualization, the types of back-up services available, potential concerns over vendor lock-in, etc.

Data entry

Pharmacy staff will need to enter information into the pharmacy software management system in order to process the prescription. Common information to require includes:

- Prescriber information -This typically includes the prescriber's name, address of practice, contact information, medical license number, DEA number, and National Provider Identifier (NPI).

- Third-party payor - This includes coverage type (primary, secondary, etc.), insurance name and bank identification number (BIN), group number, and member number.

- Patient information - The patient information should at least include name, date of birth, address, contact information, allergies, and payment type (cash vs. insurance). Often, pharmacies will request information on concurrent use of other medications and dietary supplements, preferences with respect to safety lids, verification that the patient has received notification of the pharmacy's privacy policy.

- Prescription information - While many items on a prescription are important the system should record as a minimum the date the prescription was written, superscription, inscription, subscription, signatura, refills, prescription origin code, and it should generate a unique prescription number that should appear on the prescription label as well.

- DAW codes - Dispense as written (DAW) codes need to be entered into the computer as well. Most prescriptions allow for generic substitution and patients are glad to receive the more affordable version, therefore the default DAW code is typically set to '0'. If a physician requires a specific medication to be dispensed, they will typically note this on the prescription. This is considered a DAW code of '1'. Sometimes a patient may request that they receive a brand name product even if a prescriber allowed for generic substitution. This would be classified as a DAW code of '2'. Other DAW codes are less frequently used. The following is a succinct list of the other DAW codes; 3 = substitution allowed - pharmacist selected product dispensed, 4 = substitution allowed - generic drug not in stock, 5 = substitution allowed - brand drug dispensed as generic, 6 = override, 7 = substitution not allowed - brand drug mandated by law, 8 = substitution allowed - generic drug not available in marketplace, and 9 = Other.

- Drug information - At a minimum, drug information should include the drug name, the medication's National Drug Code (NDC), the manufacturer, and an ability to check for interactions and contraindications. Often this drug information will include information on auxiliary labels, specific lot numbers and expiration dates, stock availability, pricing, and medication guides.

Filling the prescription

After completing the order entry process, the next step is to fill the medication order. A label will have been generated. You will want to verify that the information on the label is correct and complete. Then you will fill it with the appropriate medication, package it properly, and validate that everything has been done correctly.

Label

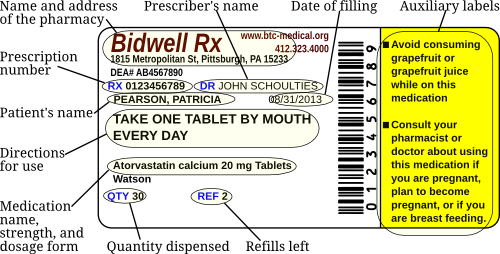

The minimal information which must appear on a dispensed prescription label includes:

- name and address of the pharmacy,

- serial (prescription) number,

- date of its filling,

- the name of the prescriber,

- the name of the patient,

- the directions for use, and

- any applicable warning (auxiliary) labels.

Also, on the federal level, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act, also known as the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), requires that on controlled substances the statement: "Caution: Federal law prohibits the transfer of this drug to any person other than the patient for whom it was prescribed."

Even though it is not required on the federal level, most prescription labels will also include the medication name, strength, and dosage form. Various states may provide additional guidelines for prescription labeling.

The following is an example of a dispensed prescription label.

Packaging

When it comes to packaging a product before it leaves the pharmacy, the prescription label is only one part of that. The packaging must be suitable for maintaining the stability of the product and offering suitable safety to both the patient and others that may have access to the medication (i.e., children). With this in mind, we need to consider whether or not the packaging provides adequate light resistance, temperature for long term and short term storage, as some products will react to some plastics you need to consider PVC vs glass containers, child safety lids are concern to protect unintentional poisonings but this needs to be balanced by sufficient ease of use for the patient, some products will require syringes (either oral or injectable) and a degree of knowledge about the intended dosage and dosage route of the medication will help with this decision.

Child safety caps

As a result of the Poison Prevention Packaging Act (PPPA), all prescription drugs and controlled dangerous substances must be packaged in child-resistant containers (i.e., packages with safety caps), with limited exceptions. The most common exceptions are if the patient or physician requests that the patient not receive child safety caps, or for emergency sublingual medications commonly used in response to angina.

If a medication is dispensed without a child safety cap, most pharmacies will note it in their pharmacy management software and often include an explanation as to why. Failure to comply with the PPPA could result in the pharmacist being prosecuted and imprisoned for not more than 1 year or sentenced to pay a fine of not more than $1000, or both.

Light resistance

There are more than 200 different medications which are light sensitive. The chemical composition of these medications can be altered by exposure to direct light. As an example, when nitroprusside is exposed to direct sun light it will breakdown into cyanide. Some common light sensitive medications include acetazolamide, doxycycline, linezolid, and zolmitriptan. While many drugs need to be protected from light while in storage, their original package from the manufacturer should suffice. If you need to repackage any medications, always be sure to consult the manufacturers recommendations to determine if you need to place the medication in light resistant packaging or not.

Temperature

The majority of medications are safe to store at controlled room temperature, 15° to 30° C or 59° to 86° F. Some medications may require refrigeration, 2° to 8° C or 36° to 46° F, or they may even need to be frozen, -25° to -10° C or -13° to 14° F, after they are dispensed (these temperature ranges have been established by the United States Pharmacopeia Convention). If the patient is picking them up from a community pharmacy, the pharmacy staff should inform the patient if special storage requirements are needed. If these medications are being dispensed by either a delivery service or a mail order pharmacy extra steps may need to be taken to help ensure that the products are maintained within proper temperature ranges, such as using cold containers with ice packs.

Container materials

Various plastics, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC) have been used in heath care for over 50 years as it is an affordable and tear resistant product that can be manipulated to achieve varying degrees of flexibility versus rigidity. For most products this is an ideal packaging material, however some medications either contain or function as plasticizers which cause them to bind to the PVC and also change the fluidity of the PVC container itself. These medications need to be stored or manipulated with products that they will not react to. Glass is a traditional option as it is an inert substance. In situations where plastics are still desirable the plastics will need to be manipulated to prevent the medications from functioning as a plasticizer by either a coating the surfaces of the container or a chemical change throughout the whole structure of the container. Nitroglycerin is a common example of this where the sublingual form and injectable forms both need to avoid prolonged exposure to traditional PVC containers.

Syringes

For patient safety, there needs to be a distinction between when to use oral/topical syringes and injectable syringes. If an oral or topical medication needs to be precisely dosed, an oral/topical syringe may be an ideal tool to dispense for the patient. They are simple to use and provide a safety factor that needles can not easily be attached to them ensuring that the patient does not receive them as an injection.

Injectable syringes also come in a wide variety of sizes with various needle options. Traditionally, prescribers will include an order for the patient's syringes and needles; although, the pharmacy staff may still need to determine the most appropriate syringes to dispense. In most states, patients may also request syringes without a prescription, but they may have difficulty getting a third-party payor to cover them.

Product validation

There are several means that may be utilized to provide proper product validation including the use of NDCs, barcode scanning technology, and a final visual verification. The pharmacy management software will have recorded a specific NDC for the medication that is being dispensed. It is a good practice to check the NDC in the computer against the product being dispensed to ensure both accuracy and to avoid any kind of billing fraud. Many pharmacy management systems also include barcode scanning to provide another double check that the NDC on the bottle matches the NDC in the computer (the barcode on the manufacturer's bottle contains the NDC). The oldest and most common form of verification is visual inspection. Traditionally this is the pharmacist that provides this role, but in some states pharmacy technicians under specific conditions are allowed to perform tech check tech. This visual verification should be looking for an accurate interpretation of the information from the original prescription to the prescription label, that the patient information on the product is correct, the the product is packaged in an appropriate manner, and that the correct drug is being dispensed.

Medication pickup

Once the medication has been filled and checked it is ready for the patient to pick it up which usually involves any payments (including copays), the offering of medication counseling, and the proper recording and filing of dispensed prescriptions.

In a community pharmacy setting a patient (or their family member, caregiver, or other authorized individual) may go to the prescription pick-up counter to receive their medication. As some patients may have the same or similar names, many pharmacies require the answer to a simple question to ensure that the medication is for the individual at the counter. Common questions include asking for their birthday or the last four digits of their social security number, which the technician can verify in the pharmacy software. At this point the technician needs to collect any necessary payments. Conveniently, many pharmacy software management systems are able to offer point of sale capabilities as well. The technician also needs to offer medication counseling to the patient, and the patient will then record in writing (whether on a physical piece of paper, or through electronic signature capture) if they want to consult the pharmacist about their therapy. If the patient requests medication counseling they will need the pharmacist. Under the privacy provisions of HIPAA, the pharmacy needs to make a valid attempt at privacy during counseling whether with something as simple as a privacy screen or with an entirely separate room. If the patient seems confused about their medication, it is a common practice for the technician to strongly suggest that the patient receive counseling or even just have the pharmacist assist the patient.

Pharmacies need to keep track of what medications have been dispensed through either the computer software and/or through the proper filing of hard copies. Prescription filing is a necessary part of working in a pharmacy. Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations - Section 1304.04 Maintenance of records and inventories - Subsection h, you will find the prescription filing options that are considered acceptable on the federal level, some states may place additional requirements on this process.

h) Each registered pharmacy shall maintain the inventories and records of controlled substances as follows:

(1) Inventories and records of all controlled substances listed in Schedule I and II shall be maintained separately from all other records of the pharmacy.

(2) Paper prescriptions for Schedule II controlled substances shall be maintained at the registered location in a separate prescription file.

(3) Inventories and records of Schedules III, IV, and V controlled substances shall be maintained either separately from all other records of the pharmacy or in such form that the information required is readily retrievable from ordinary business records of the pharmacy.

(4) Paper prescriptions for Schedules III, IV, and V controlled substances shall be maintained at the registered location either in a separate prescription file for Schedules III, IV, and V controlled substances only or in such form that they are readily retrievable from the other prescription records of the pharmacy. Prescriptions will be deemed readily retrievable if, at the time they are initially filed, the face of the prescription is stamped in red ink in the lower right corner with the letter "C" no less than 1 inch high and filed either in the prescription file for controlled substances listed in Schedules I and II or in the usual consecutively numbered prescription file for noncontrolled substances. However, if a pharmacy employs a computer application for prescriptions that permits identification by prescription number and retrieval of original documents by prescriber name, patient's name, drug dispensed, and date filled, then the requirement to mark the hard copy prescription with a red "C" is waived.

(5) Records of electronic prescriptions for controlled substances shall be maintained in an application that meets the requirements of part 1311 of this chapter. The computers on which the records are maintained may be located at another location, but the records must be readily retrievable at the registered location if requested by the Administration or other law enforcement agent. The electronic application must be capable of printing out or transferring the records in a format that is readily understandable to an Administration or other law enforcement agent at the registered location. Electronic copies of prescription records must be sortable by prescriber name, patient name, drug dispensed, and date filled.

You may view this on the DEA's Diversion Control website at http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/cfr/1304/1304_04.htm

Also, while not a requirement, a common pharmacy practice is to stamp their Schedule-II medication with an 'N' stamp to denote it as a narcotic and make it easily identifiable from other prescriptions.

See also

The Joint Commission

Medication errors

Poison Prevention Packaging Act

Medicaid Tamper-Resistant Prescription Law

References

- Pocket Guide for Pharmacy Technicians, 2nd Ed., Jahangir Moini, Delmar Publishing, ISBN: 978-1111306649, pp 99-110, 2012

- Shannon Parsons, PharmD, interview conducted July 16, 2013

- Heath Reynolds, Speed Script representative, interviewed and technical assistance provided July 9, 2013

- Prescription Drug Benefit Manual, Rev. 11, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, February 19, 2010, http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/downloads/Chapter7.pdf

- Clerical and Data Management for the Pharmacy Technician, Linda Quiett, Delmar Publishing, ISBN: 978-1439057810, p 38, 2012

- Medicaid Compliant Tamper Resistant Rx Paper, http://www.medicaidrxpaper.com/

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid Tamper Resistant Pescription Law – Pharmacist FACT SHEET, https://www.cms.gov/FraudAbuseforProfs/Downloads/pharmacisfactsheet.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Calculations, v. 1.0, Sean Parsons, Parsons Printing Press, ISBN: 978-0578063737, pp 171-204, 275-298, 2012

- USP 36-NF 31, United States Pharmacopeial Convention, ISBN: 978-19364241222012, 2012

- Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations - Section 1304.04, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/cfr/1304/1304_04.htm

- Pharmacy Times, A Review of Federal Legislation Affecting Pharmacy Practice, Virgil Van Dusen , RPh, JD and Alan R. Spies , RPh, MBA, JD, PhD, https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200612-01.asp

- Strauss's Federal Drug Laws and Examination Review, Fifth Edition (revised), Steven Strauss, CRC Press, 2000

- Food and Drug Administration, Legislation, http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/default.htm

- Food and Drug Administration, History, http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/default.htm

- 16 CFR 1700.14, January 1, 2010, http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2010/janqtr/16cfr1700.14.htm

- Prescription Origin Code (Data Element), U.S. Health Information Knowledge Database, http://ushik.ahrq.gov/recordExport.pdf?system=mdr&itemKey=61831000&format=pdf&enableAsynchronousLoading=true

- Telecommunications Questions and Answers, v. 5, National Council for Prescription Drug Programs, May, 2013, http://www.ncpdp.org/members/pdf/VersionD.Editorial.pdf

- Polyvinyl chloride, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyvinyl_chloride#Healthcare

- Electronic Prescriptions for Controlled Substances (EPCS), Office of Diversion Control, http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/ecomm/e_rx/faq/practitioners.htm