Pharmacoinformatics

From Rx-wiki

This article will cover the following major concepts related to pharmacoinformatics:

- Pharmacy-related computer applications for documenting the dispensing of prescriptions or medication orders (e.g., maintaining the electronic medical record, patient adherence, risk factors, alcohol drug use, drug allergies, side effects)

- Databases, pharmacy computer applications, and documentation management (e.g., user access, drug database, interface, inventory report, usage reports, override reports, diversion reports)

Contents

- 1 Terminology

- 2 Databases

- 3 Medication use process

- 4 Specific pharmacy automations and technologies

- 4.1 EHR

- 4.2 E-prescribing

- 4.3 CPOE

- 4.4 IVR

- 4.5 Pharmacy management software systems

- 4.6 Barcoding technologies

- 4.7 Automated counting and dispensing technologies

- 4.8 Automated compounding devices

- 4.9 Automated cart-fill systems

- 4.10 Automated storage and retrieval systems

- 4.11 Automated dispensing cabinets

- 4.12 Automated prescription pick-up

- 4.13 Reconciliation and profit analyzing technologies

- 4.14 Pharmacy kiosks

- 4.15 Telemedicine

- 4.16 Telepharmacy

- 4.17 Pneumatic tube systems

- 4.18 Robotic delivery systems

- 5 Challenges to implementing pharmacy automation and technology

- 6 The future of pharmacy information systems

- 7 See also

- 8 References

Terminology

To get started in this article, there are some terms that should be defined.

database - A database is an organized collection of data.

database management system (DBMS) - A database management system (DBMS) is a software system designed to allow the definition, creation, querying, update, and administration of databases.

query - In computing, a query is a precise request for information retrieval with database and information systems.

health information exchange (HIE) - Health information exchange (HIE) is the mobilization of healthcare information electronically across organizations within a region, community or hospital system.

pharmacy informatics - Pharmacy informatics (a.k.a., pharmacoinformatics) is the use and integration of data, information, knowledge, technology, and automation in the medication use process. The goal of this integration is to improve health outcomes.

reconciliation - In pharmacy, the term reconciliation can have two different definitions. Reconciliation can involve correcting a pharmacy charge to correspond with the proper fees for the item dispensed. Reconciliation can mean evaluating the patient's response to a therapy and making the necessary changes to better ensure that the patient's medical treatment better coincides with their needs.

cart-fill - Cart-fill (sometimes listed as cartfill) is the process of providing patients with a short term supply of all the medications they need (typically 24 hours worth). This process is commonly practiced in institutional settings.

computer cracker - A computer cracker is someone who makes unauthorized use of a computer, especially to tamper with data or programs. The media commonly refers to these individuals as hackers.

Databases

Pharmacy information systems are providing the backbone for today's plethora of pharmacy automation and technology, as they need to be able to access vast quantities of information to perform their necessary functions. These databases usually require someone with a strong understanding of how technology actually works to be properly implemented as they will need to determine what kind of database management system to use (i.e., MySQL/MariaDB, PostgreSQL, MS SQL, Oracle Database, etc.) and how they want information to be added (entering it directly into the database, other software interfaces that connect to the database being allowed to write to the database, replicating existing databases and maintaining updates against the other databases, or by other means).

This field is commonly referred to as pharmacoinformatics.

How a database works

The common database interactions can be broken into four main groups:

- Data definition - Defining new data structures for a database, removing data structures from the database, modifying the structure of existing data.

- Update - Inserting, modifying, and deleting data.

- Retrieval - Obtaining information either for end-user queries and reports, or for processing by applications.

- Administration - Registering and monitoring users, enforcing data security, monitoring performance, maintaining data integrity, dealing with concurrency control, and recovering information if the system fails.

Advantages

As these databases become more robust, they are able to readily organize large quantities of data that can be easily queried. This information is quickly retrievable, and databases do not tire of repetitive search strings, achieving a higher degree of accuracy and speed than what could be achieved without them.

Challenges

A number of challenges exist with creating and maintaining databases. A common challenge is getting the information from one database to communicate with a different database (especially if they are using different database management systems). A database is not generally portable across different database management systems, but different database management systems can interoperate by using standards such as SQL and ODBC or JDBC to allow a single application to work with more than one database. Health information exchanges have been developed to help with this process.

Security is another significant challenge, as many applications may need to be able to query information from these databases while still keeping unauthorized individuals from accessing the information. Database access control deals with controlling who (a person or a certain computer program) is allowed to access what information in the database. The information may comprise specific database objects (e.g., record types, specific records, data structures), certain computations over certain objects (e.g., query types, or specific queries), or utilizing specific access paths to the former (e.g., using specific indexes or other data structures to access information). Database access controls are set by special authorized (by the database owner) personnel that uses dedicated protected security database management system interfaces. This may be managed directly on an individual basis, or by the assignment of individuals and privileges to groups, or (in the most elaborate models) through the assignment of individuals and groups to roles which are then granted entitlements. Data security prevents unauthorized users from viewing or updating the database. Using passwords, users are allowed access to the entire database or subsets of it called "subschemas". For example, an employee database can contain all the data about an individual employee, but one group of users may be authorized to view only payroll data, while others are only allowed access to work with history and medical data. The database management system provides a way to interactively enter and update the database, as well as interrogate it. This capability allows for database management.

Medication use process

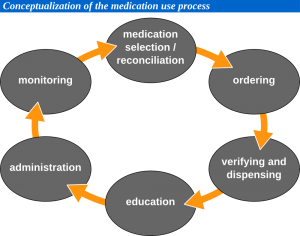

Pharmacy information systems have become so common and well integrated that they can directly impact every step of the medication use process. To the right is a brief flowchart explaining the medication use process.

Medication selection

Prescribers have become accustomed to consulting databases in their electronic health records when selecting medications in order to assure that the medications are covered, or to seek prior authorization if they deem a non covered medication to be necessary.

Ordering

Physicians, whether seeing a patient at their practice or rounding at an institution, commonly utilize e-prescribing and/or computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) to order medications from the pharmacy. Physicians may also place orders using the pharmacy's interactive voice response (IVR) system.

Verifying and dispensing

In the case of CPOE, pharmacies only need to verify the medication and the appropriateness of the prescription (the pharmacy management software will help to screen for various interactions). E-prescribing commonly connects to modern pharmacy management systems; although, the pharmacy may still need to enter the prescription information into the system in a different manner to process it.

In both community pharmacy and institutional pharmacy, it has become common to scan barcodes on medications prior to them being dispensed to ensure accuracy.

In community pharmacy, the pharmacy may use an electronic signature capture to verify who picked the medication up, and to verify whether or not the patient desires counseling. Also, in some communities, pharmacy kiosks have begun to appear providing a convenient means of getting a common medication filled, or to pick-up a medication refill.

In many institutions, automated dispensing cabinets, robotic delivery systems, and/or pneumatic tube systems may be utilized to dispense the medications to the nursing units.

Education

The clinical decision support (CDS) tools allow for easy access to patient education points and guides including applicable warnings, contraindications, and side effects. On some medications where medication guides are mandatory, the pharmacy management systems will often prompt the pharmacy to provide the necessary information.

Telemedicine and telepharmacy have been implemented in many places, providing greater access for patients located either off-site or in rural areas to health care providers. This increased availability allows for improved patient education opportunities as well.

Administration

In outpatient settings, there has been a number of niche technology products intended to help patients take their medications in a timely fashion, ranging from simple alarms all the way to automated pill dispensing boxes that the pharmacy may program for the patient.

On the side of institutional medications, the integrated hospital software will remind nurses when to give patients their medications. Patient bedside barcode scanners will assure that the right medication is being given to the right patient at the right time, and often, even provide the right documentation by automatically charting the medication as being given.

Monitoring

Pharmacy technology exists in both inpatient and outpatient settings to monitor patient adherence by recording when medications have been given (or missed), and to monitor biological data such as blood sugar, blood pressure, etc. As the technologies to record this information continue to evolve, expect to see more of this information recorded on the patients' electronic health records.

Reconciliation

By accumulating and disseminating this information, it allows the entire health care team, including pharmacy, to make better decisions about what changes may need to be done to improve the patient's quality of life.

Specific pharmacy automations and technologies

Many technologies have already been named in this article, but this section will explain a little bit more about each of these technologies. As you read this section, it will be easy to see how technology can improve clinical decisions and outcomes, speed, accuracy, space utilization, and inventory management.

EHR

An electronic health record (EHR) is a collection of electronic health information about individual patients. It is a record in digital format that is theoretically capable of being shared across different health care settings. This sharing often occurs by way of network-connected, enterprise-wide information systems and other information networks or exchanges. These exchanges are sometimes referred to as health information exchanges (HIEs). EHRs may contain a range of data, including demographics, medical history, medication and allergies, immunization status, laboratory test results, radiology images, vital signs, personal statistics (like age and weight), and billing information.

As EHRs are still rapidly evolving, not all information has been transferred into them. Working backwards, there will be challenges gathering and entering all pertinent information from the past if it is not readily retrievable, but this is a short term problem, as all data moving forward should be entered into the necessary databases.

E-prescribing

E-prescribing is the computer-based electronic generation, transmission, and filling of a medical prescription, taking the place of paper and faxed prescriptions. E-prescribing allows a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant to electronically transmit a new prescription or renewal authorization to a community or mail-order pharmacy.

E-prescribing provides the following benefits:

- Improving patient safety and quality of care - Illegibility from handwritten prescriptions is eliminated, decreasing the risk of medication errors. Also, oral miscommunication regarding prescriptions can be reduced, as e-prescribing should decrease the need for phone calls between prescribers and dispensers.

- Reducing time spent on phone calls and call backs to pharmacies - Many written prescriptions can be ambiguous and require pharmacies to call the prescriber, leave a message, and wait for a call back. This translates into less time available to the pharmacist for other important functions. E-prescribing can significantly improve this situation by reducing the volume of pharmacy call backs related to illegibility, mistaken prescription choices, formulary and pharmacy benefits.

- Automating the prescription renewal request and authorization process - With e-prescribing, renewal authorization can be an automated process that provides efficiencies for both the prescriber and pharmacist. Pharmacy staff can generate a renewal request (authorization request) that is delivered through the electronic network to the prescriber's system. The prescriber can then review the request, and act accordingly by approving or denying the request through updating the system. With limited resource utilization, and just a few clicks on behalf of the prescriber, they can complete a medication renewal and maintain continuous patient documentation.

- Increasing patient convenience and medication compliance - It is estimated that 20% of paper-based prescription orders go unfilled by the patient, partly due to the hassle of dropping off a paper prescription and waiting for it to be filled. By eliminating or reducing this waiting period, e-prescribing may help reduce the number of unfilled prescriptions and increase medication compliance. Allowing the renewal of medications through this electronic system also helps improve the efficiency of this process, reducing obstacles that may result in less patient compliance. Availability of information on when patient's prescriptions are filled can also help clinicians assess patient compliance.

- Improving formulary adherence permits lower cost drug substitutions - By checking with the patient's health plan or insurance coverage at the point of care, generic substitutions or lower cost therapeutic alternatives can be encouraged to help reduce patient costs. Lower costs may also help improve patient compliance.

- Allowing greater prescriber mobility - Improved prescriber convenience can be achieved when using mobile devices that work on a wireless network, to write and renew prescriptions. Such mobile devices may include laptops, tablets, and smart phones. This freedom of mobility allows prescribers to write/renew prescriptions anywhere, even when not in the office.

- Improving drug surveillance/recall ability - E-prescribing systems enable embedded, automated analytic tools to produce queries and reports, which would be close to impossible with a paper-based system. Common examples of such reporting would be: finding all patients with a particular prescription during a drug recall, or the frequency and types of medication provided by certain health care providers.

CPOE

Computerized prescriber order entry, also called computerized physician order entry, is a process of electronic entry of practitioner instructions for the treatment of patients under their care. CPOE systems are used for processing orders in institutional settings.

The following is a list of features associated with CPOE:

- Customized-standardized ordering sets - Physician orders are standardized across the organization, yet may be individualized for each prescriber or specialty by using order sets. Orders are communicated to all departments and involved caregivers, improving response time and avoiding scheduling problems and conflict with existing orders.

- Patient-centered decision support - The ordering process includes a display of the patient's medical history and current results, and evidence based clinical guidelines to support treatment decisions.

- Patient safety features - The CPOE system allows real-time patient identification, drug dose recommendations, adverse drug reaction reviews, and checks on allergies and test or treatment conflicts. Physicians, nurses, and pharmacists can review orders immediately for confirmation.

- Regulatory compliance and security - Access is secure, and a permanent record is created with electronic signature.

- Portability - The system accepts and manages orders for all departments at the point-of-care, from any location in the health system (physician's office, hospital or home) through a variety of devices, including PCs, tablets, smart phones, and other devices.

- Health system reporting - The system delivers statistical reports online so that managers can analyze patient census and make changes in staffing, replace inventory, and audit utilization and productivity throughout the organization. Data is collected for training, planning, and root cause analysis for patient safety events.

- Billing accuracy - Documentation is improved by linking diagnoses to orders at the time of order entry to support appropriate charges.

IVR

Interactive voice response (IVR) is a technology that allows a computer to interact with people through the use of voice and dial tones. IVR applications can be used to control almost any function where the interface can be broken down into a series of simple interactions. In pharmacy, these systems are commonly used to direct phone calls, and order refills; physicians will frequently use them to phone in new prescriptions and/or clarifications.

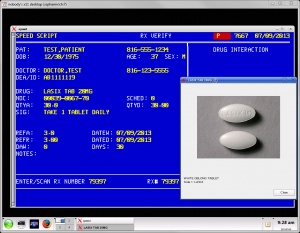

Pharmacy management software systems

Pharmacy management software systems are the all-in-one tool that many community pharmacies depend on. Pharmacy management systems are usually capable of performing the following tasks:- prescription processing

- e-prescribing

- prescription pick-up with signature capture

- refill queue

- work flow manager

- prescription scanning and patient card scanning

- medication guides, care points, and REMS

- NDC check and prescription verification processing

- third party adjudication, including major medical insurance and worker’s comp

- accounts receivable processing

- point of sale capabilities

- DME/CMS 1500 on-line billing

- 340B inventory control management and reports

- wholesaler interface with automated ordering

- nursing home and LTC batch processing

- wireless signature capture/delivery manifest module

- MTM services billing electronically

- compounding services support

Barcoding technologies

Automated counting and dispensing technologies

Counting out large numbers of tablets and capsules by hand can be a very laborious task, especially in today's high volume pharmacies. Tablet counting machines are able to assist in this process, as they can count tablets quickly and accurately. These machines will manage these rapid counts in a number of ways. Some will use an electronic 'eye' to count the medications as they fall through, others will know the weight of specific medication tablets or capsules and determine the quantity based on the total weight poured into the vial, while others will use specially designed hoppers that will deliver medications as the tray inside the cassette spins.

Many of the new high-end tablet counters can even receive prescriptions from the pharmacy management software, fill the vials, and label them once the ordered has been processed. Kirby Lester, Aesynt Baker Cells, and ScriptPro Systems are commonly used automated tablet counters.

Automated compounding devices

An automated compounding device (ACD) is a machine used to prepare compounded sterile preparations, such as parenteral nutrition. The manual method of parenteral nutrition admixture compounding is labor-intensive and requires multiple manipulations of infusion containers, sets, syringes, needles, and so forth, which can lead to the extrinsic contamination of the final admixture with sterile and nonsterile contaminants.

These ACDs not only automate the compounding process providing improved turn around time and accuracy, but many of the newer ACDs can also help with many of the more complex concepts such as: limits for anions/cations, osmolarity warnings, volume warnings, and calcium/phosphate solubility.

Automated cart-fill systems

Robotic arms have been developed for pharmacies that can operate on vertical and horizontal rails. Operating in an enclosed area, these robotic arms move up and down aisles filled with pegs containing individual drug doses stored in plastic, bar-coded pouches. The arms pick the appropriate medications and drops them into either patient specific envelopes or cassettes, which can then be used for the cart-fill.

Automatic tablet dispensing and packaging systems may vary in design and capacity, but they typically contain hundreds of containers with each container being capable of holding a different medication. The medications will be dispensed in long strips that contain patient specific medications in the order that the patient is scheduled to receive them.

Automated storage and retrieval systems

As the name implies, these systems may be used to both store and retrieve pharmacy inventory. Instead of needing to move up and down aisles in the pharmacy to acquire this inventory, these systems can store materials in tightly packed spaces on vertically rotating carousels that can bring the items to the staff. When an automated pick list is either run on the machine, or if a particular medication barcode is scanned, the machine will properly rotate the materials to the pharmacy team member.Automated dispensing cabinets

An automated dispensing cabinet (ADC) is a computerized drug storage device or cabinet designed for institutional settings. ADCs allow medications to be stored and dispensed near the point of care, while controlling and tracking drug distribution. Facilities that use ADCs typically use them to manage floor stock medications, PRNs, and controlled substances. Some pharmacies will also use them to provide quick access to emergency medications, common drugs, or even all the medications on a patient profile.Due to the fact that these systems are commonly located throughout a hospital, additional security is often implemented on these systems ranging from the use of user names and passwords, to barcode scanning and biometric identification.

Automated prescription pick-up

Automated prescription pick-up can have two potential pieces. The first, which is very widely utilized, are automatic prescription refill services where the pharmacy will automatically generate a refill for specific patient medications. Many of these systems will notify the patient through telephone message, email, or even text message that their refill is ready.

The second part, which is less common, is placing medications that have already been filled into machines that patients can access without going to the pharmacy counter. This frees up the staff from waiting on customers that do not need additional services, and can help reduce work loads during high volume periods of the day. It also provides the opportunity for a patient to pick-up a medication after the pharmacy has already closed. If a patient does decide they have a question for a pharmacist, these systems include phones and video cameras so that they can still receive counseling from either an on-site pharmacist or even one located remotely.

Reconciliation and profit analyzing technologies

A challenge for many pharmacies can be to receive full and proper payment for all their medications dispensed. Automated rebilling services can be set-up to receive orders that didn't pay-out, and look at what might be done differently to get the prescriptions to process. Also, these systems often have the ability to connect to the pharmacy software and correct prices related to average wholesale prices (AWP) for both brand and generic medications, which in-turn will also help with pharmacy revenues.

Pharmacy kiosks

Some facilities, particularly grocery stores without pharmacies, have started using pharmacy kiosks. These kiosks have the ability to scan patient insurance cards, IDs, and prescriptions for a pharmacy to remotely review and enter. These machines will contain the most common medications (usually excluding controlled substances), and with a pharmacist's authorization, will fill these prescriptions, including placing patient labels on the vials. Through the use of video cameras and phone receivers, a pharmacist will offer patient counseling at the kiosk. The patient will typically be able to pay for their prescription with either a credit card or debit card to complete the process.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine is the use of telecommunication and information technologies in order to eliminate distance barriers and improve access to medical services. Telemedicine can be broken into three main categories: store-and-forward, remote monitoring, and (real-time) interactive services.

Store-and-forward telemedicine involves acquiring medical data, and then transmitting this data to an appropriate medical professional at a convenient time for assessment off-line. It does not require the presence of both parties at the same time.

Remote monitoring, also known as self-monitoring or testing, enables medical professionals to monitor a patient remotely using various technological devices. This method is primarily used for managing chronic diseases or specific conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, or asthma.

Interactive telemedicine services provide real-time interactions between patient and provider, to include phone conversations, online communication and home visits. Many activities such as history review, physical examination, psychiatric evaluations, and ophthalmology assessments can be conducted through this means.

Telepharmacy

Telepharmacy is the delivery of pharmaceutical care via telecommunications to patients in locations where they may not have direct contact with a pharmacist. It is an instance of the wider phenomenon of telemedicine, as implemented in the field of pharmacy. Telepharmacy services include drug therapy monitoring, patient counseling, prior authorization and refill authorization for prescription drugs, and monitoring of formulary compliance with the aid of teleconferencing or videoconferencing. Remote dispensing of medications by automated packaging and labeling systems can also be thought of as an instance of telepharmacy. Telepharmacy services can be delivered at retail pharmacy sites or through hospitals, nursing homes, or other medical care facilities.

The term can also refer to the use of video conferencing in pharmacy for other purposes, such as providing education, training, and management services to pharmacists and pharmacy staff remotely.

Pneumatic tube systems

Pneumatic tubes are systems that propel cylindrical containers through a network of tubes by compressed air or by partial vacuum. These systems are sometimes employed for pharmacy drive-throughs, to provide increased convenience to customers. These systems are even more common in hospital settings, providing a rapid means to transport medications, devices, and other necessary materials throughout the facility in a very rapid manner.

While pneumatic tubes can safely transport most items under 2 kg, there are some items that institutions and pharmacies ban including:

- controlled substances, if the tubes are not able to be sent and received in a sufficiently secure manner,

- drugs with long protein chains, as there is a concern that the vibrations in a pneumatic tube system may damage them,

- glass containers, also because of concern that the vibrations may damage them,

- live modalities (i.e., medicinal leeches),

- hazardous liquids due to concerns of leakage and exposure of the entire pneumatic tube system to these materials.

While pneumatic tube systems are not a new technology, they continue to improve and gain more complex features, such as having security codes that can be changed on the fly so only authorized individuals can access them, the ability to notify specific staff members when particular tubes arrive on the unit, and the inclusion of GPS tracking devices to identify their physical location.

Robotic delivery systems

If materials need to be delivered to the nursing units, and these items cannot be sent using a pneumatic tube system, another option involves the use of robotic delivery systems. These robots can navigate through hospital corridors and elevators to transport materials from the pharmacy to the hospital floors. These robots can work around the clock, and make both scheduled and on-demand deliveries. They can deliver something as small as a single IV or an entire unit’s medication order.

Challenges to implementing pharmacy automation and technology

While it is common to focus on the positives associated with pharmacy automation and technology, there are significant challenges to overcome including: staff and customers that are change adverse, direct and indirect costs associated with implementing new automation and technology, and concerns over maintaining patient confidentiality.

Resistance to change

Most people achieve certain routines in how they perform various tasks, whether they are simple or complex, and in pharmacy this is true of the pharmacy staff as well as their clients (patients, nurses, physicians, etc.). They have certain expectations as to how long a particular task will take and what the outcome will be. A challenge to implementing any type of automation or technology is that it will require changes to these routines in order to be implemented. Generally, it will help if all individuals involved know what the new technology is, why it is being implemented, and discussion about what the expected gains are versus the potential challenges can be reviewed. It is also helpful to follow-up after implementation to discuss any unforeseen outcomes, whether good or bad.

Cost

While these automations claim they can reduce existing HR salaries and benefits, improve productivity and workflow efficiency, and enhance operation services, there is the challenge that the costs on some of these technologies can be overwhelming. Depending on complexity, staff knowledge, product competition, and sheer manufacturing costs, the prices on this equipment can range from free (if looking at an open source IVR that your own staff knows how to install and maintain, although staff time does till have some costs associated with it) to millions of dollars (such as some of the high end robotic arms that perform cart-fill procedures and fill first-dose medications in some institutions). Another cost to consider is the support contracts that pharmacies often need for all this cutting edge technology.

Confidentiality issues

While all this health information collection and integration provides opportunities to improve patient care, it does raise concerns over maintaining patient confidentiality, as so many health care entities may have access. According to a Los Angeles Times article (At Risk of Exposure, June, 6, 2006), roughly 150 people (from doctors and nurses, to technicians and billing clerks) have access to at least part of a patient's records during a hospitalization, and 600,000 payers, providers, and other entities that handle providers' billing data have some access as well.

There are three potential sources for security failures with respect to this information: human, environmental threats, and technology failures. Human threats include employees inappropriately accessing information and/or not securing it, as well as threats from computer crackers (sometimes called hackers by the media). Environmental threats can range from earthquakes and hurricanes to fires and floods. These environmental threats may unintentionally expose patient sensitive information, commonly referred to as protect health information (PHI). Technology failures could include hardware and software failures that could either be related to the other two security failures or independent of them.

Standards need to be met to ensure the security of this information, along with strict guidelines about who should have access to specific patient information. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 does publish standards for security. The security standards are designed to protect the confidentiality of PHI that is threatened by the possibility of unauthorized access and interception during electronic transmission. Like the privacy provisions, any pharmacy that transmits any health information in electronic form is required to comply with the security rules.

In particular, the security standards define administrative, physical, and technical safeguards that the pharmacist must consider in order to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI.

A unique aspect of the security provisions is that they include both "required and addressable" implementation specifications. Required implementation specifications are those that must be met, whereas, in addressable specifications, the pharmacy must determine whether the suggested safeguards are reasonable and appropriate, given the size and capability of the organization, as well as the risk.

While cost may be a factor that a covered entity may consider in determining whether to implement a particular specification, nonetheless a clear requirement exists that adequate security measures be implemented. Cost considerations are not meant to exempt covered entities from this responsibility.

The future of pharmacy information systems

With all of these advancements, the true end-goals are improved patient outcomes through a variety of means including: health care providers with greater access to the relevant information, more educated patients, improved medication and therapy compliance, better reporting, reduced errors, and more opportunities for patients to communicate with their health care providers. While great advancements have been made in these areas, more integration needs to be achieved as these technologies mature and new ones are developed.

As these services and information systems become more advanced, they are changing the role of both pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. Some particular areas of expected growth include:

- As electronic health records eventually achieve full integration with a patient's entire medical history, it will allow for better screening of potential medication errors, and help to better identify patients that may benefit from from medication therapy management (MTM).

- Greater autonomy will likely be achieved by pharmacy technicians as they can rely on automation to reduce the possibilities of making errors.

- Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians will need to learn more about how to properly interact with and maintain this equipment.

- This specialized area of knowledge will also offer future growth opportunities to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians that understand both pharmacy and the information technology component. These specialized pharmacy personnel will be utilized by pharmacies, institutions, and the automation companies.

See also

Medication order entry and fill process

References

- Database, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Database

- Electronic health records, Wikipedia, http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_health_records

- Electronic prescribing, Wikipedia, http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/E-prescribing

- Computerized physician order entry, Wikipedia, http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/CPOE

- The New England Journal of Medicine, Effect of Bar-Code Technology on the Safety of Medication Administration, Eric G. Poon, M.D., M.P.H., et al., http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa0907115#t=article, May 6, 2010

- Patient Safety and Quality Healthcare, Improving Medication Safety with a Wireless, Mobile Barcode System in a Community Hospital, Mitch Work, http://www.psqh.com/mayjun05/casestudy.html, May/June 2005

- Interactive voice response, Wikipedia, http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivr

- Heath Reynolds, Speed Script representative, interviewed and technical assistance provided July 9, 2013

- Clerical and Data Management for the Pharmacy Technician, Linda Quiett, Delmar Publishing, ISBN: 978-1439057810, p 38, 2012

- At Risk of Exposure, Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2006

- Betsy Martinelli - Senior Manager of Corporate Marketing for Aesynt Incorporated, June 30, 2014